The Kashmir Conflict and International Peace and Security:

Post August 2019

Madeeha Majid

Contrary to what many nations claim, there is nothing truly domestic in an increasingly globalized world. This is more so in case of conflict, which has far reaching ramifications beyond geographical limitations, affecting human as well as collective security. One such issue is the Kashmir conflict. Essentially involving fundamental rights and aspirations of the Kashmiri people, the Kashmir conflict is warped in territorial claims and aggression between three major nuclear powers.

Internationally, the United Nation’s principal political organ, the Security Council, is placed with the primary responsibility of maintaining international peace and security. The relevance of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in the case of Kashmir has been quite visible since the beginning of the conflict. After India approached the UNSC against Pakistan over Kashmir for endangering international peace and security in 1947, the UNSC passed resolutions to end hostilities between the two countries. The UNSC established a United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) to investigate the facts of the dispute and to exercise a mediatory role in the resolution of the crisis. Importantly, UNSC through its resolutions, set forth a two-part recommendation calling for ‘demilitarisation’ of the region, following which, a ‘plebiscite’ would be conducted with the help of a UN Plebiscite Administrator. These recommendations were reiterated in many subsequent UNSC Resolutions. The United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was also formed to help observe and report to the UN from the region.

However, due to the absence of any enforcement action, the resolution adopted created little change on ground. Thus, even though the parties had obligations both under customary international law (to act in good faith), as well as the UN Charter (to respect the decisions), the plebiscite could not be conducted. Many termed the behaviour of the parties as out of line with the UN Charter and morally wrong. The relevant UNSC resolutions on Kashmir, apart from being criticised for form and scope, were also condemned for not giving Kashmiris the option to seek an independent country for themselves. Such a position of the Security Council was the result of the absence of any understanding between India and Pakistan to pursue an all-Kashmiri settlement. This was also reflective of the heavily state-centric approach to international law during that time.

After a second war was fought between India and Pakistan in 1965 over the region, the Security Council again called upon the parties to use peaceful means. In the following years up until 1971, more resolutions were passed and the issue of Kashmir was regularly on the agenda of UNSC. A considerable change in UNSC’s practice was seen with the signing of the Simla Agreement between India and Pakistan post the Bangladesh War, which significantly diminished UNSC’s role in the region. Although some argue that the UNSC played a role in the Kashmir dispute by not playing a role, there are considerable arguments against bilateralism stating that India and Pakistan used it as a shield to bring their own ‘radical, dysfunctional, and incommensurable issues to the table’, halting any real progress on the issue.

Moreover, during the Cold War period, as the Security Council was grappling with issues elsewhere (such as Kosovo, Yugoslavia, Somalia, East Timor, etc.), its overall approach towards Kashmir lacked any bearing, even in the face of an armed conflict between Kashmiri fighters (allegedly aided by Pakistani soldiers) and the Indian security forces. As the Kashmir issue receded to the margins of international diplomatic fora, India declared the region to be an integral part of the country, where all its boundaries are fixed, final, and non-negotiable. This left little scope for negotiation, negating the purposes of the Shimla agreement. Since then, until now strict adherence to bilateralism has resulted in the creation of a stalemate.

However, the status quo changed post August 5, 2019. The de-operationalization of the special status of the Indian Controlled Kashmir has visibly escalated tensions in the region, presenting grave implications for international peace and security. It is clear that the prolonged conflict has sustained hostilities between the three nuclear powers. Thus, an international armed conflict is plausible in the future, along with the risk of terrorist groups like ISIS (also referred to as ISIL or Daesh) finding ground in the region. Taking note of the situation, the Security Council held a closed door meeting on the issue in August 2019, after many decades of not discussing it.

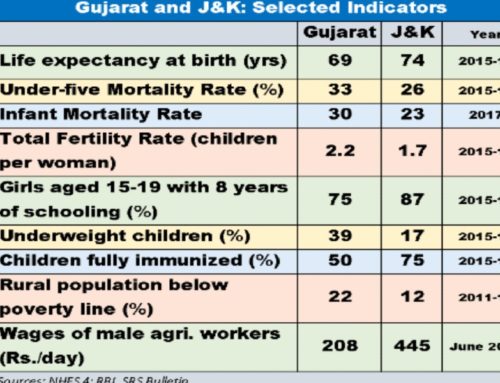

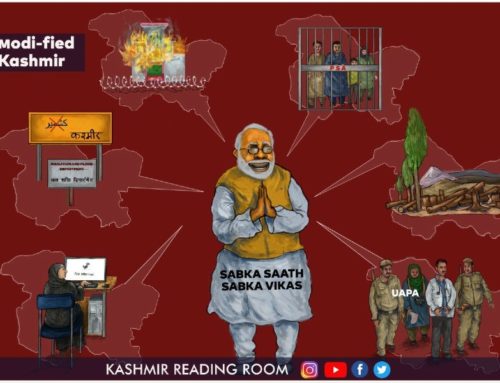

Besides the change in the local laws, and bifurcation of the state, the most controversial aspect of the Indian decision pertains to the abolishing of the region´s almost 100-year-old permanent residency rules. This drew vehement criticism for attempting to change the demography of the region. Many termed the move to be unconstitutional under Indian national laws, while others argued for its qualification as an unlawful annexation, resulting in the de jure occupation of the territory under international law.

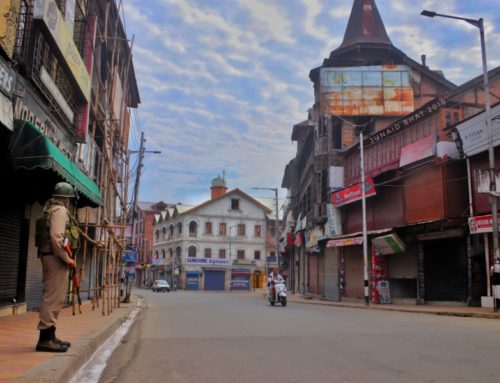

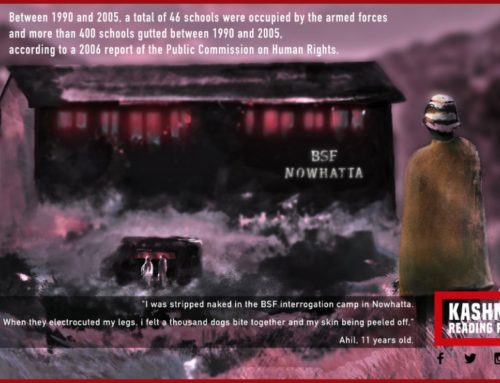

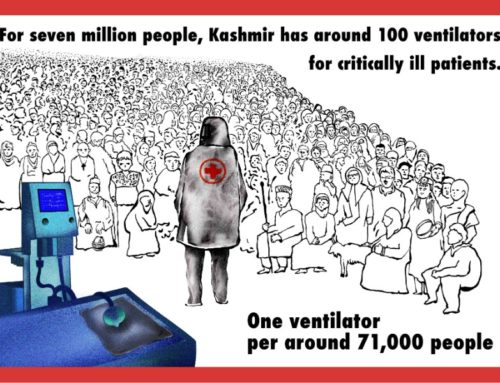

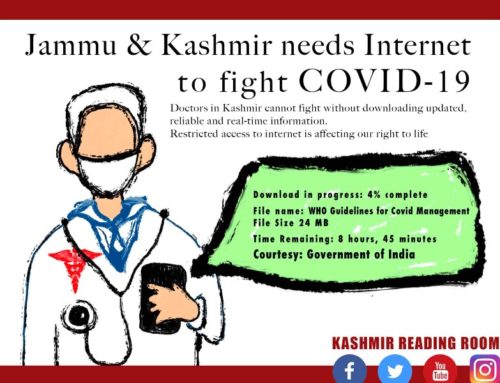

Already prevailing decades of heavy militarisation and human rights violations had led to a pattern of impunity and a denial of justice in the region. Adding to it, the change in status quo has intensified tensions between India and Pakistan, and also triggered incursions and clashes in eastern Ladakh, along the LAC (Line of Actual Control) between India and China (May/June 2020).

Assuming, arguendo, that the Kashmir conflict, which began as an internationalised dispute, has condensed into a bilateral dispute, the recent incursions of China in the Indian controlled Ladakh region have added a new party to the dispute. China’s aggressive politics and alleged use of force, in the background of its multilateral investments in the disputed territory of Pakistan Controlled Kashmir, has increased its interests to promote stability and economic growth in the region, making it a major stakeholder in the issue. China’s position is also significant due to its membership (as a P5 member), capable of substantively impacting the handling of the dispute at the Security Council. Chinese support for Pakistan’s efforts to internationalize the Kashmir issue had declined over the past few decades. However, they have revived post Kashmir’s changed status.

Undoubtedly, Chinese policies on Kashmir affect regional stabilization and crisis management efforts in South Asia. China has in the past, raised concerns about rising tensions in Kashmir and reiterated calls for a peaceful resolution of the dispute through dialogue and consultation. As mentioned, on China’s call (at the request of its ally, Pakistan) for the first time since 1971, the Kashmir issue was discussed by the UNSC in a closed door meeting in August 2019. Even though the Council failed to come out with a statement, the meeting carried symbolic weight as it helped to internationalize the issue once again. Thus, even though China’s strategy remains ambiguous, the Kashmir crisis has already exceeded the bilateral framework. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for the international community to exert moderating pressure upon all sides of the conflict, bringing them to a table to negotiate. Such a conducive environment for peace talks can only be created when the States, by means of the UNSC, fulfil their obligations to resolve the crisis, which is at the brink of a political and humanitarian catastrophe. Within its competencies, the UN must operate to keep peace and contain the conflict, while also ensuring justice for those affected. Lastly, and most importantly, the people of Kashmir, often overlooked in the state binary, must remain primary parties, relevant to any resolution of the conflict.

References

-

- United Nations, Charter of the United Nations, 24 October 1945, 1 UNTS XVI, Preamble, available at, https://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/preamble/. S.D. Bailey & S. Daws, The Procedure of the UN Security Council, 3rd ed. (1998).

- Letter from the Representative of India to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc. S/RES/628 (1 January 1948).

- UNSC Res. 39 (1948), on establishing a Commission on the India-Pakistan question, UN Doc. S/RES/39 (20 January 1948).

- UNSC Res. 91(1951), on deciding to appoint a UN Representative for India and Pakistan in succession to Sir Owen Dixon, UN Doc. S/RES/ 91 (30 March 1951); UNSC Res. 99 (1951) on a plan for the demilitarization of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, UN Doc. S/RES/96 (10 November 1951); UNSC Res. 98 (1952) on negotiations to reach an agreement on a plan of demilitarization of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, UN Doc. S/RES/98 (23 December 1952); UNSC Res. 122 (1957), on the final disposition of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, UN Doc. S/RES/122 (24 January 1957); UNSC Res. 122 (1957), on negotiations on the India-Pakistan question and visit of the UN Presentative for India and Pakistan to the subcontinent, UN Doc. S/RES/126 (2 December 1957).

- Sonnenfeld R. Resolutions of the UNSC, Polish Scientific Publishers, (1998).

- On the binding-ness of UNSC Resolutions, See, Advisory Opinion, Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), (1971) ICJ Rep 16 at 113.

- International Crisis Group (ICG), India, Pakistan, and Kashmir: Stabilising a Cold Peace, Asia Briefing, No. 51 (Brussels: ICG, June 2006).

- Schaffer, H. The Limits of Influence: America’s Role in Kashmir, An ADST-DACOR Diplomats and Diplomacy Book, Brookings Institution Press, (2009).

- “The American Diplomat at the UN criticized the form and scope of the Security Council’s resolutions, as being unrealistic and ineffective because they depended on India and Pakistan cooperating with the council and failed to give it authority to impose sanction.” H. Schaffer, The Limits of Influence: America’s Role in Kashmir, An ADST-DACOR Diplomats and Diplomacy Book, Brookings Institution Press, (2009).

- Hashmi, R. S. & Sajid, Kashmir Conflict: The Nationalistic Perspective (A Pre-Partition Phenomenon) 31 Research Journal of South Asian Studies, No. 1, 219 – 233 (January – June 2017).

- Birdwood, C. India and Pakistan: A Continent Decides, Frederick A Praeger (1954) at 262.

- UNSC Res. 211 (1965), on demanding immediate cease-fire and subsequent withdrawal of armed personnel from the State of Jammu and Kashmir, UN Doc. S/RES/211 (1965).

- Lamb, A (1994). Birth of a tragedy. Roxford Books.

- Qerimi, Q (2013). The S Word and Security Council: The Role and Powers of the United Nations Security Council in the Creation of New States, 36 TJLR 181

- Sharpe, M. E. (2016). Kashmir in the Shadow of War, Regional Rivalries in a Nuclear Age. Routledge; 1 ed.

- Widmalm, S. (2002). Kashmir in Comparative Perspective: Democracy and Violent Separatism in India, Psychology Press at 44.

- (30 July 2018) ‘Integrity of India’s borders non-negotiable: CBFC chief on Kashmir references in Mission: Impossible (Eds: Updating with changes in intro)’. Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/integrity-of-indias-borders-nonnegotiable-cbfc-chief-on-kashmir-references-in-mission-impossible-eds-updating-with-changes-in-intro/1360352.

- Ganguly. S (1997). The Crisis in Kashmir: Potents of War, Hopes of Peace 1st ed.

- Wenning, H (2003). Kashmir: A Regional Conflict with Global Impact, 1 NZJPIL

- Butt, A (7 August 2019). ‘India just pulled Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy. Here’s why that is a big deal for this contested region.’ Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/08/07/india-just-pulled-jammu-kashmirs-autonomy-heres-why-this-is-big-deal-this-contested-region/

- UN News (16 August 2019). ‘UN Security Council discusses Kashmir; China urges India and Pakistan to ease tensions’. UN News. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044401

- Letter from the Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the UN, UN Doc. S/2019/654 (13 August 2019); Letter from the Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the UN addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2020/431, (21 May 2020). M. Ganguly, India Failing on Kashmiri Human Rights: Some Easing, but Abusive Restrictions Persist, Human Rights Watch, available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/01/17/india-failing-kashmiri-human-rights. (17th January 2020)

- Chandrachud, A (2020). The Abrogation of Article 370, in Essays and Reminiscences: A Festschrift in Honour of Nani A. Palkhivala, A. P Datar (ed.), 1st Ed.

- A. B. Soofi, & Ors., Legal Memorandum, Legal Memorandum, The Status of Jammu & Kashmir Under International Law: The Law of Occupation and Illegal Annexation, Research Society of International Law, Pakistan (2019).

- UN Human Rights Council, OHCHR, Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Kashmir: Developments in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir from June 2016 to April 2018, and General Human Rights Concerns in Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan (14 June 2018) (Henceforth, OHCHR Reports).

- Butt, A (7 August 2019). ‘India just pulled Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy. Here’s why that is a big deal for this contested region’, Washington Post, Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/08/07/india-just-pulled-jammu-kashmirs-autonomy-heres-why-this-is-big-deal-this-contested-region/ (Last Accessed on 14-06-2020).

- Krishnan, A (12 June 2020). ‘Beijing think-tank links scrapping of Article 370 to LAC tensions. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/beijing-think-tank-links-scrapping-of-article-370-to-lac-tensions/article31815266.ece

- Hussain, I (2004). Kashmir Dispute, An International Law perspective 2nd Ed.

- Chang, I.J (2017). China’s Kashmir Policies and Crisis Management in South Asia. US Institute of Peace.

- Ibid.

- Roth, R (16 August 2019). ‘UN Security Council Has its First Meeting on Kashmir in Decades — and Fails to Agree on a Statement, CNN’. CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2019/08/16/asia/un-security-council-kashmir-intl/index.html

- Jianxue, L. (18 August 2019). ‘India Is Playing with Fire on Kashmir, Global Times’. Global TImes. Retrieved from http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1161857.shtml

- Simma, Bruno & Ors., The Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary 3rd Ed., Volume I, Oxford University Press, (2012) at 332.

- Lone, F.N. Historical Title, Self-Determination and the Kashmir Question, 7 Brill’s Asian Law Series (2018).

- Quigley, J. Displaced Palestinians and a Right to Return 39 HJIL 192 (1998).

- Lone, F.N. ‘The Creation story of Kashmiri People: The Right to Self-Determination’ 21 The Denning Law Journal 1-25 (2009).

About the Author: Madeeha Majid is an Advanced L.L.M. student of Public International Law at Leiden University, pursuing her specialisation in Peace, Justice and Development. The paper is an extract from her Advanced L.L.M. thesis at Leiden University. (2019-2020).

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.