Amidst Harassment and Persecution, Resilient Journalism Continues

Freny Manecksha

The amendment of Article 370 and turning Kashmir into a Union Territory was front page material for all major national Indian papers. Some of the newspaper headlines on August 6, 2019 read:

“Kashmir is now Union’s Territory” (The Times of India)

“Territory of the Union” (The Hindustan Time)

“History, in one Stroke” (The Indian Express)

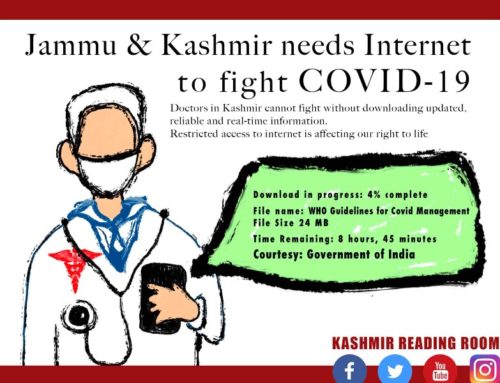

But, for anyone perusing the archives decades and decades from now, there will be no mention of such history reflected in Kashmir’s newspapers or websites. Jammu & Kashmir’s (J&K) vibrant press of some 414 empaneled newspapers, of which 172 are in Kashmir (about 60 in Urdu and 40 English), were muzzled by the covert operations of the Indian state and by measures that had been put in place for over a week.

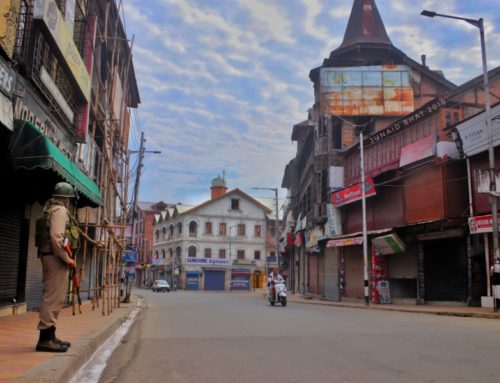

These included – (1) a complete telecommunication shutdown with snapping of special lines for internet services of news portals and online editions of papers from midnight; (2) a similar shutdown of internet, mobile phones and even landlines; (3) restrictions on physical movement with concertina wire rolled out and checkpoints blocking access to highways, roads and even smaller lanes of towns and cities; (4) a vast carceral operation that included imprisonment of hundreds and hundreds of mainstream political leaders, activists, lawyers and youths. In addition, hundreds of youths were picked up and held under illegal detentions in police stations.

So, whilst national papers could publish a tightly controlled government narrative, the English daily Greater Kashmir could, in comparison record the historic run up to events with only this last update on its website at around 1.20 am on August 5, 2019:

“Omar Mehbooba Lone placed under house arrest, restrictions imposed in Srinagar, mobile internet suspended.”

Besides a halt in uploading and updating the online editions, the free flow of information came to a grinding halt. As senior journalist Parvaiz Bukhari, associated with a foreign news agency pointed out, it was impossible to counter the propaganda peddled by the state because of the internet shutdown. Moreover, journalists were unable to verify and confirm any information they received because of the total disruption of mobile phones and landlines. Even the authorities were not able to triangulate it.

Editors lost contact with their stringers or reporters. Those who had vital and important information to share were unable to impart it. Offices were shut. Vital communication and links with people were snapped.

Kaisar Andrabi, a freelancer who writes for The Wire, First Post and so on said, “It was frustrating to be unable to report despite having information.”

There was also the issue of being part of the news but unable to record it. Qazi Zaid who runs and edits the news platform Free Press Kashmir recalled how one of the last stories they did was on the panic: how panic was being manufactured and how it affected them too. “We aren’t just reporting the conflict. We are living it.”

The severe restrictions on movement for at least two weeks, and state surveillance made it difficult for editors to even physically go in search for their reporters in rural areas, one editor pointed out.

Urban researcher and writer Stephen Graham has argued that infrastructure is not just a ‘thing’ or ‘system’ or an ‘output’, but a complex social and technological process that enables or disables particular kinds of action in the city. He has analysed the way it can be used as new militarism especially citing Palestinian dispossession. One can well use this insight for Kashmir where the complete dismantling of infrastructure and the deployment of ‘security’ concerns to suppress democratic dissent, had a profound and lasting impact on print journalism.

Most newspapers were not able to bring out editions and were forced to suspend publications till August 17 at least. In some cases, the newspapers had run out of newsprint. About three major publications and some five to six others came out with truncated editions with a much lower print order, but were also hampered by erratic distribution.

For news portals like Free Press Kashmir, the entire revenue model was almost totally destroyed by a prolonged spell of shutdown. Entrepreneur Qazi Zaid was forced to go out of Kashmir and try and think out ways and means to ensure his 15 young journalists were not rendered jobless with the closure that went on for more than four months.

The publications also underwent a dramatic metamorphosis in content and tone, with almost total capitulation, echoing the government’s Naya Kashmir narrative. As Majid Maqbool notes, the crucial stories and issues of the shutdown on the region’s economy and healthcare went missing from the front pages of Kashmir’s major dailies. Editorials and opinion columns practised self-censorship, or, in a most bizarre manner, chose non-political subjects like changing food habits, benefits of Botox therapy, climate change: anything but the humanitarian crisis unfolding around them.

Newspapers even carried full page government advertisements pronouncing ‘benefits of Abrogation of Article 370.’ This provided the key to understanding this capitulation. Earlier, in February the government had banned advertisements for Greater Kashmir and Kashmir Reader. The drastic decrease in revenue forced newspapers to curtail salaries. Majority of papers in Kashmir are dependent on advertisements by the Department of Information and Public Relations (DIPR).

The editors had also been summoned by a federal investigation agency concerning the conflict in Kashmir. Such coercive tactics and threats of financial throttling had the desired effect. Papers began curtailing reports and details of militants’ funerals even before the siege. In Kashmir, funerals have for long served as a very emotive and passionate space for dissent. In fact, the government has now used the pandemic as an excuse not to hand over bodies of those slain in encounters to relatives and family.

Besides these tactics, there was increased surveillance of newspapers and intimidation. It was ratcheted up considerably just before and during the August siege. Qazi Shibli, the young editor of Kashmiriyat was summoned on July 27 by the J&K Police about a news story relating to information about a government order on troop movements. That was the last his family saw of him for nearly 10 months. Shibli was arrested under the Public Safety Act and flown to jail and released only this year, that too after a prolonged online campaign. In December, TIME magazine listed Shibli on the fifth spot in ‘10 Most Urgent Threats to Press Freedom’.

Irfan Malik of Tral who worked with Greater Kashmir was also picked up by police from his home. His distraught family travelled all the way to access the government-controlled Media Centre that had been set up in Srinagar on August 10 to convey the news to other members of the press since the offices of Greater Kashmir were closed. His detention and release on a personal bond were reported in the Indian media and he was released on a personal bond but the reasons for his arrest were never made clear.

In another example of pressure being unofficially applied, senior journalists like Fayaz Bukhari, Aijaz Hussai and Nazir Masoodi, working with reputed publications or associated with the international media, were verbally asked to vacate their government allotted accommodation.

On August 31, Gowhar Geelani, whose book had just been released, was prevented from flying to Germany to attend a workshop. He was stopped by immigration authorities and no reason was offered.

One important intervention with regard to the struggle for Kashmir’s access to a free media came in mid-August when Anuradha Bhasin, editor of the Srinagar edition of Kashmir Times approached the Supreme Court arguing that the internet is essential for the modern press and that by shutting it down the print media had come to a grinding halt, and that she had been unable to publish her newspaper. This, and the restrictions to movement, she argued, were violations of Article 19 of the Indian Constitution which guarantees the right to freedom of expression.

Meanwhile, the government had set up a Media Facilitation Centre at a private hotel with five computers, a BSNL internet line and one phone controlled by officers, attached to the Directorate of Information and Public Relations (DIPR). Journalists had to queue up for hours to access the internet for emails, communicate with editors and then upload their stories or even entire pages. A whole day could be spent in uploading just one file. As one journalist pointed out the tedious process was a cruel irony in a world where breaking news demands information flows at lightning speed. At the Facilitation Centre, journalists would have to pitch stories, wait for response, upload reports or visual images and then provide details or clarifications when sought by editors, and this two-way process could take days.

More importantly, as Majid Maqbool pointed out, such complete dependence on the government and submission to its regulations in a bid to tame journalists made a mockery of the notion of freedom of press.

And yet with near impossible working conditions, fears of personal safety and increased surveillance, Kashmir’s journalists, many of whom were freelancers, rose to the challenge and ground level stories from Kashmir began coming out in the international media and some news portals in India. The information flow was re-established by intrepid journalists and photojournalists, going into the rural regions and parts of Srinagar and sending out reports and visual images and videos through flash drives carried out of Kashmir by travelers.

Yasin Dar, senior photo journalist with the foreign agency AP, who was honoured with the Pulitzer in 2020 along with Mukhtar Khan and Channi Anand, described the process: “It was always cat-and-mouse,” he said. “The challenges made us more determined than ever never to be silenced.”

His agency, AP, paid tribute to the way the trio had captured images of protests, police and paramilitary action, and daily life by snaking around roadblocks, sometimes taking cover in strangers’ homes and hiding cameras in vegetable bags.

These tactics and their determination could well apply to many of the other photojournalists from Kashmir, most of whom felt compelled as Kashmiris to responsibly record the people’s voices. Among the independent photojournalists were two young women, Sanna Irshad Matto and Masrat Zehra, whose images, many of which have a gender perspective, have been carried internationally with reputed agencies and publications.

By September, the truth was out, and India’s controlled narrative had been shredded. Reports of torture and forced labour in army camps, the healthcare crisis, the protests in Saura on August 8 and renewed defiance and the huge arrests appeared in publications like BBC, Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New York Times, Washington Post, France 24 and so on. For years no foreign media had been allowed to report out of Kashmir but, now, as the joke in Kashmir’s Press Club went, Kashmir’s local journalists had gone international.

Ahmer Khan, a freelancer and his team were also honoured by the 24th Human Rights award for a short video on the resistance by people of Aanchar. It is yet another example of acknowledgement by the world of Kashmir’s turbulence captured by its media. Ahmer Khan also received the Kate Webb award for successfully documenting tension, concerns and frustrations of the residents of Srinagar and other areas in Kashmir. He personally travelled to New Delhi to file his stories.

If the awards were seen as a collective honour for Kashmir’s journalists, their collective stand against the growing intimidation was reflected by a post on social media initiated by senior journalists Muzamil Jaleel and Auquib Javeed. Entitled “Operation Enforced Silence” it lists the names of those who have suffered beatings, intimidation by the police and had FIRs filed against them:

In the growing list are the following:

- On November 2, Muzamil Mattoo was beaten up by police in downtown Srinagar whilst covering prayers.

- On November 30 Basharat Masood of Indian Express and Hakeem Irfan of Economic Times were summoned by the counter-insurgency grid and grilled for stories they had carried.

- On December 2, Ishfaq Reshi had an FIR filed against him for naming government forces in a report he filed on the burning of haystack in Budgam.

- On December 17, Anees Zargar was beaten up in public view and threatened for his reports against police officers.

- On December 17, Azaan Javaid was similarly beaten whilst covering a protest and he was threatened for filing reports against police officers.

- On February 8, Haroon Nabi was summoned to the counter insurgency centre and questioned in connection with a report carrying a statement by the JKLF.

- On February 8, an FIR was also filed against Naseer Ganai for a report carrying a JKLF statement.

- On April 17, Mushtaq Ahmed was beaten up in Bandipora for reporting during the lockdown.

With the restoration of 3G, another trend of heightened surveillance of social media was noted, with the cyber-police now charging journalists with various crimes. The first instance was of senior journalist Peerzada Ashiq of the Hindu, who was summoned by the Anantnag police in connection with the headline of a report regarding the exhumation of bodies of three militants. Ashiq had quoted the relatives as saying that permission had been given for exhumation but police claimed it had not been given and termed his report as ‘fake news.’ Ashiq’s report was based on a conversation with the kin who had mistaken curfew passes with exhumation. It was argued that whilst there was a technical error his entire report could not be termed as fake news.

Days later, the young woman photojournalist Masrat Zahra learnt from social media that she had been charged under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). At first it was not even clear why and for what she was being charged. It later emerged she was charged for uploading one of her older images that had been used earlier by an international website. The image depicted a Shia procession with one of the participants carrying a poster of Burhan Wani, the deceased commander of the Hizbul Mujahideen and the epithet ‘shaheed.’

Then Gowhar Geelani also learnt he had been charged under UAPA. He was summoned and questioned by police and charged with conducting unlawful activities through social media posts, but no specific post was named. A huge outcry has followed these latest instances of intimidation on the front runners of journalism, the reporters and photojournalists. Significantly, it is now UAPA, a law with very stringent measures that is being applied. It is, as Sanjay Kak argues, something much more serious than interference in the performance of journalistic duties. “In her [Masrat Zahra] case they did not even use the word journalist about her, she was charged just for doing what she had done, as an individual using social media. I see these as signals meant to terrorize young people and stem the circulation of ideas at the very source, in the spaces where those thoughts are generated.”

She has since been awarded the Anja Niedringhaus Courage in Photojournalism Award for “depicting conflict in Indian controlled Kashmir and its toll on local communities” and was praised by the jury for her photographs, which were described as being filled with a sense of “dread and community.”

Another strategy adopted by the cyber police is to call upon all Kashmiris to publicly acknowledge that they are under surveillance by making them sign an undertaking that they will not post anything that has ‘unlawful content’.

The definition of unlawful can remain as vague and ambivalent as the authorities see fit.

Remarking on the constricted spaces for Kashmir’s media, a veteran journalist remarked that whilst there was nothing new about intimidation, the scale and brazenness was messaging as clear as it can get. But, he added, who in the world has ever succeeded in stopping journalism?

References

- Onmanorama (6 August 2019). ‘’History, in one stroke’: How front pages of English newspapers reported Article 370 cancellation’. Onmanorama. Retrived from https://www.onmanorama.com/news/nation/2019/08/06/english-newspapers-jammu-and-kashmir-coverage-media.html

- Aafaq, Z (2 October 2019., ‘‘We may have to shut down permanently’: Online Media In Kashmir Has Come to a Grinding Halt’. The Polis Project. Retrieved from https://thepolisproject.com/we-may-have-to-shut-down-permanently-online-media-in-kashmir-has-come-to-a-grinding-halt-by-zafar-aafaq/#.XvieFigzZPY

- Ibid.

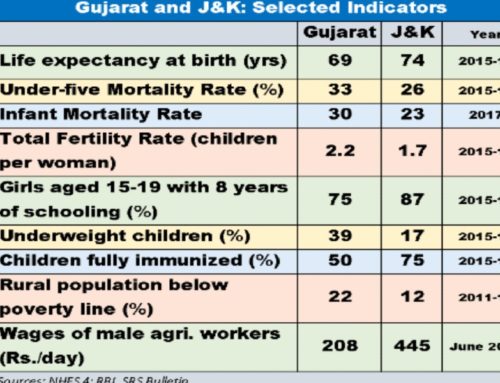

- Bakshi, A (18 October 2019. ‘Dystopia vs development: The Kashmir paradox’. Livemint. Retrieved from https://www.livemint.com/mint-lounge/features/dystopia-vs-development-the-kashmir-paradox-11571377960811.html

- Ibid.

- Maqbool, M (16 January 2020). ‘Keeping journalism alive in Kashmir’. Himal. Retrieved from https://www.himalmag.com/keeping-journalism-alive-in-kashmir/

- Sharma, Y (3 May 2020). ‘A Kashmiri journalist on his recent detention’. Popula. Retrieved from https://popula.com/2020/05/03/kashmiri-journalist-qazi-shibli-on-his-recent-detention/

- Ahmad, M (17 August 2019., ‘Kashmir: Journalist Detained by Security Forces Released’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/media/kashmir-journalist-irfan-amin-malik-detained

- (4 September 2019). News Behind the Barbed Wire: Kashmir’s Information Blockade. Retrieved from http://www.nwmindia.org/images/articles_pdf/Kashmir_2019_News_Behind_the_Barbed_Wire_A_Report.pdf

- Supra note 523.

- Peltz, J (5 May 2020. ‘AP wins feature photography Pulitzer for Kashmir coverage’. Associated Press. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/366a717b2c1b9a677fcbd533e9b225c2

- FPK (7 May 2020), ‘Defending Kashmir: Ahmer Khan and team awarded 24th Human Rights Press Award’. Free Press Kashmir. Retrieved from https://freepresskashmir.news/2020/05/07/defending-kashmir-ahmer-khan-and-team-awarded-24th-human-rights-press-award/

- Ashiq, P (19 April 2020). ‘Families of slain militants given curfew pass’. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/families-of-slain-militants-given-curfew-pass/article31378804.ece

- Qanungo, N. G (5 June 2020. ‘Sanjay Kak: ‘Kashmir lays India bare. Old clichés of democracy, constitution, free media now look very shallow’’. The Polis Project. Retrieved from https://www.thepolisproject.com/sanjay-kak-kashmir-lays-india-bare-old-cliches-of-democracy-constitution-free-media-now-look-very-shallow/#.Xvs9_CgzZPY

- Staudenmaier, R (11 June 2020. ‘Kashmir conflict photographer Masrat Zahra wins top photojournalism award’. DW. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/kashmir-conflict-photographer-masrat-zahra-wins-top-photojournalism-award/a-53775419

About the Author: Freny Manecksha is an independent journalist from Mumbai. She has authored ‘Behold, I Shine. Narratives of Kashmir’s Women and Children’.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.