Debunking the Colonial Discourse:

Gender and Kashmir

Misbah Reshi

Introduction

Immediately after Article 370 of the Indian Constitution was amended to write down the special status guaranteed to Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), there was an outpouring of speeches and comments by Indian men rejoicing over the possibility of marrying Kashmiri women. Manohar Lal Khattar, Chief Minister of Haryana said, “Some people are now saying that as Kashmir is open, brides will be brought from there…”. BJP Member of the Legislative Assembly from Haryana, Vikram Saini said, “Muslim party workers should rejoice in the new provisions. They can now marry the white-skinned women of Kashmir.” There was also a surge in Google search for ‘Kashmiri girl’ post August 5 and scores of tweets and videos were circulated by Indian men celebrating the amendment as it was easing their chances of marrying Kashmiri women.

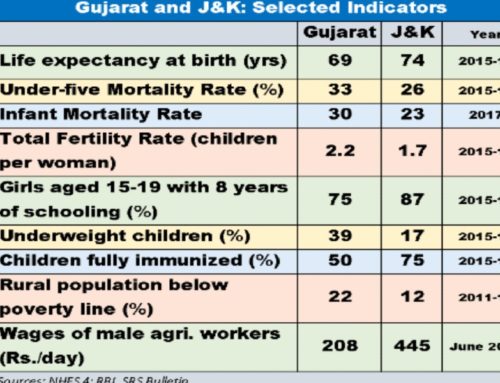

This provided an important insight into the larger purpose for which the amendment was brought, and more importantly, how it was received by the people of India. Article 370 of the Constitution of India, argued the ruling government in India, was a barrier to development in the valley and specifically an obstacle to the emancipation of women and LGBTQ community. Jay Panda, the national Vice President of BJP argued that the removal of Article 370 would help eliminate discrimination against women and the LGBTQ community and would make the valley ‘infinitely better’.

Ironically, while Kashmir was still under a movement lockdown and an internet shutdown, on January 26 commemorated as the Republic Day of India, the country invited Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who is known to be openly sexist and homophobic. He has made statements like he would rather have his son die in an accident than come out as a homosexual and he won’t rape a fellow female legislator because she “doesn’t deserve it”.

While the state’s explicit narrative remained progressive, the real intention was far from it, as was the reaction of the Indian masses. The objectification and fetishization of Kashmiri women along with a desire to control and conquer their bodies is a reflection of the deep-rooted desire to control such women whose identity has challenged the idea of India. It is an outcome of the hyper-masculine nationalist identity glorified under the current regime but one that has always existed in mainland India and has sought to assert its power through different forms of violence on the bodies of Kashmiri women. The reaction of Indians celebrating the amendment passed on August 5, 2019 was a direct and immediate reaction of the very desire to conquer and control Kashmiri women and the Kashmiri territory.

Through this chapter, I will firstly identify the falsehoods propagated by the ruling government to further their narrative on the removal of Kashmir’s special status. I will then trace all the aggressions and violations meted out by the state in Kashmir on women and LGBTQ community and how they are evidence to challenge the state’s claim of empowerment and emancipation.

Peddling Misconceptions

There were many misconceptions and falsehoods that were deliberately propagated to the Indian masses for them to celebrate the removal of Kashmir’s special status.

One such misconception, which was important for their narrative of women’s empowerment, was that Article 35A of the Indian constitution prevented Kashmiri women, who married non-Kashmiris, from purchasing land. In the case of State of J&K v. Dr. Susheela Sawhney, the J&K High Court clarified that a woman retains her right to inherit and own property in J&K even after she marries a non- Kashmiri. An interpretation by a Kashmiri lawyer of the definition of ‘state subject’ stated in a notification dated April 20, 1927, is that, Note-II of the definition is gender neutral. It states, “The descendants of the persons who have secured the status of any class of the state subjects will be entitled to become the state subjects of the same class” hence children of Kashmiri women who are state subjects would also be considered state subjects.

Another misconception peddled in the name of the LGBTQ community was that progressive judgments of the Supreme Court like the recognition of transgender as a third gender and the de-criminalisation of homosexuality, could not be implemented in Kashmir due to Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. In 1995, the J&K High Court in Jankar Singh v. State & Ors. had upheld that judgments of the Supreme Court of India are binding on the courts in Jammu & Kashmir. The same was concurred by multiple jurists and legal scholars, as well as former High Court judge, Justice Hasnain Masoodi. This provides evidence to the fact that there was no merit in the claims made by the ruling government that their motives were for the benefit of the community.

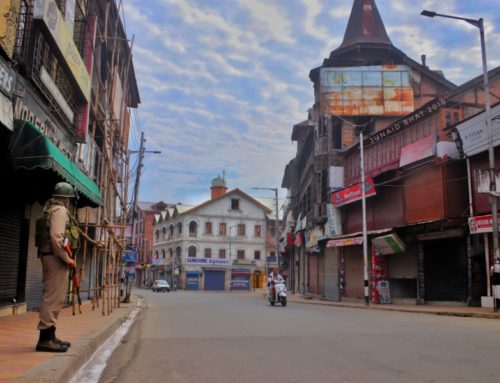

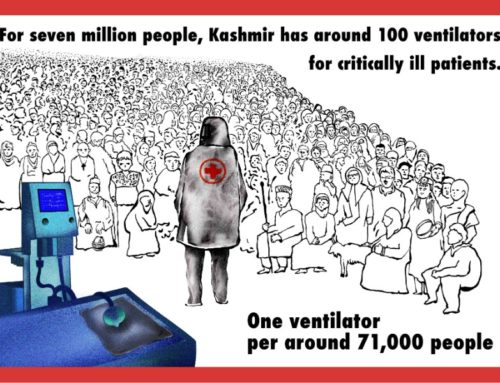

The complete communication and movement lockdown imposed in the valley post August 5, detrimentally impacted women and members of the LGBTQ community, more than others. Given that the state claimed the change in the legal status of the valley was for the betterment of its vulnerable communities, it made no provisions for their needs during the lockdown. This exposed how the use of their identities was an afterthought justification for the state, and not a policy decision.

Babloo, a transgender person was reported as saying, “India took a drastic step by scrapping Article 370 and did it at the wrong time. Everything has vanished. We do matchmaking and cater to families who are associated with businesses, how will they pay us when they do not have means to survive for themselves. I have not earned a single penny after the abrogation of Article 370 and I am completely dependent on my brother.” The August 5 state-imposed lockdown severally affected the ability of transgender persons to sustain themselves. Without providing for any welfare benefits, the state imposed the lockdown leaving the already socially and economically vulnerable community to fend for themselves.

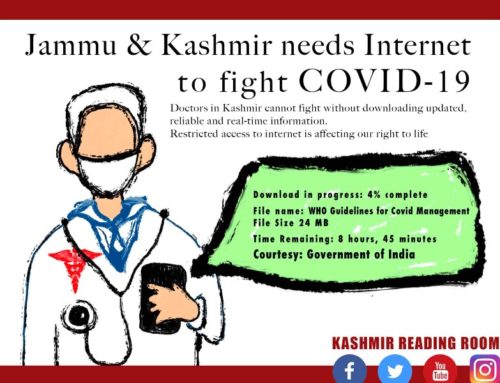

August 5, 2019 marked an important date not only for Kashmiris but also for the transgender community in India as Lok Sabha passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019 on the same date. This Act has been a cause of concern for members of the transgender community, who in large number vehemently rejected it, for being discriminatory and violative of their basic rights like the right to self-identify. The transgender community of Kashmir was under a communication shutdown which made it impossible for them to be aware of the developments that were taking place. Further, despite protests against the Act, the government of India released draft rules for the Act during the COVID-19 lockdown, seeking comments and suggestions. Kashmir had access to only 2G internet services and in many places even that was erratic which meant that there was an information blackout for the transgender community in Kashmir who could not contribute their point of view on the policy. Since the internet shutdown and the notification on the draft rules were both passed under the authority of the central government, it is clear that there was no intention of the government to redress the concerns of transgender persons in Kashmir and work for their upliftment.

The state also made no provisions for special circumstances that exclusively affect women. A 26-year-old pregnant woman, while in labour, could not reach the hospital and was on the verge of giving birth on the roadside. Security forces, despite knowing her condition, refused to allow her to move past the various checkpoints that had been set up by them.

Violence By Authorities

Women in Kashmir have historically been active participants in the resistance to state machinery. They were active participants during the 1931 rebellion against Dogra rule, in 1940s during Quit Kashmir movement, and even during 1990s when violence in Kashmir was extreme. Women’s participation in protests post August 5, 2019 was inevitable and scores of women took to the streets to assert their complete rejection of the government’s move stated to be for their benefit. Unsurprisingly, the authorities in the valley responded to their protests with violence.

It was reported that Rabiya, a lady from Soura in Srinagar was briefly detained by the police and kept in a room full of male detainees. She stated, “I kept asking them to let me go as I have a two-year-old daughter to feed. To which the SHO (police officer) replied ‘don’t worry, if your baby dies, they will bring the body here.’ He also threatened me saying he’ll slaughter the people of my neighbourhood.”

In Renawari, Srinaar, the authorities, specifically the Station House Office of J&K Police, were targeting women. It was reported, “The SHO asked her to deliver the baby on the road but did not allow her to visit the hospital. I ask, which law is this police officer following,”

While searching for protestors in Noorbagh in Srinagar, 16-year-old Soliha Jan, was beaten mercilessly by the police to the point where she vomited blood and fainted. She was admitted in the hospital’s emergency ward and it took her two weeks to recover.

Prominent female voices in the valley have also been suppressed. Masrat Zahra, a Kashmiri photojournalist was booked under UAPA for covering the human impact of the conflict and posting them on her social media, which the state calls “anti-national posts with criminal intention to induce the youth.”

Militarisation

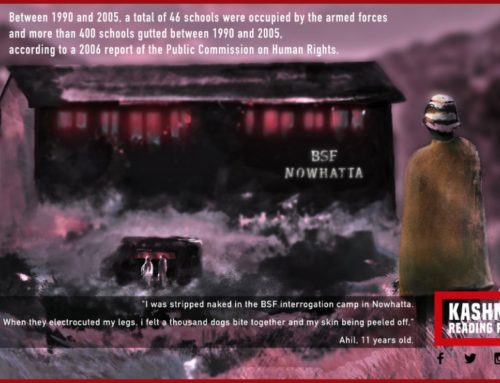

The valley has been a site of violence and conflict for decades with the existence of heavy militarised presence and exceptional laws like The Armed Forces (Jammu And Kashmir) Special Power Acts, 1990 and Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1987. This has created a culture of impunity in the valley where there have been 8000+ enforced disappearances, 70,000+ deaths, countless cases of torture and sexual violence and discovery of 6000+ unknown and unmarked mass graves. As reported by Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Societies, a human rights group in Kashmir, the first six months of 2020 witnessed the extrajudicial executions of at least 32 civilians in J&K, in which 3 were children and 2 were women.

This culture of impunity has created a hostile environment for all Kashmiris but more so for women and LGBTQ individuals. They have been subjects of sexual violence at the hands of armed forced in the valley, much of which has been reported and documented. On February 23, 1991, in the villages of Kunan-Poshpura, army men from 4 Rajputana Rifles, 68 Brigades were accused of mass rape of women (number varying from 32 to 70) during a night crackdown. The police didn’t lodge the First Information Report (FIR) and incessantly denied the charges against the army. On May 30, 2009, in the southern district of Shopian, the dead bodies of two young women, Neelofer Jan and Asiya Jan, aged 22 and 17 respectively, were found lying in the stream. The police refused to register a First Information Report (FIR) or to send the bodies for post-mortem. Based on forensic and autopsy reports, it was confirmed that the two women were raped and there was willful tampering of evidence to perpetuate silence. On June 26, 1990, members of the Border Security Force (BSF) raped Hasina, a young girl from Sopore during a search operation. The accused members were charged of rape based on medical evidence like vaginal bleeding and bite marks on her face, chest, and breasts, yet there was no further follow up on the case. In another case, the rape and murder of a bride and her pregnant aunt by BSF personnel is evidence of non-compliance with ordinary laws of the land. In 2016, a sixteen-year-old girl from Handwara was sexually assaulted by a soldier while she was using a public bathroom.

The state has made no efforts to bring the victims of sexual violence to justice and has in fact denied the occurrence all such cases. The denial of victimhood and not providing them with a fair trial is antithetical not just to rule of law, but also to all liberating progressive politics including feminist and LGBTQ political frameworks.

Conclusion

India, much like its British colonisers, has a saviour complex. It creates the imagery of a villainised Pakistan along with a villainised male Kashmiri Muslim who is not only a threat to Indians but also its own community’s vulnerable sections like women and LGBTQ persons. India portrays itself as the nation that needs to save and protect Kashmiri women and the Kashmiri LGBTQ community, while in reality its actions have only caused their marginalisation.

But the current regime in India has a larger plan. Ideologically driven by the RSS, Kashmir plays an integral role in their Hindutva agenda, as they claim the region to have roots of the Hindu spiritual ideology. The change in the domicile law which allows Indians to purchase land and settle is a big step in changing the demography to their desire and a step to owning and conquering the land and bodies of Kashmiri women. The existence of a vast majority that have not only strongly resisted Hindutva, but all statist forces, is a barrier to their larger plan. The state of affairs in Kashmir, with incessant violence on marginalised bodies, is hence a reaction to such resistance.

Kashmiri women and LGBTQ individuals are being used by the Indian state to further oppressive and violent policies in Kashmir. There is no truth in the claim that the removal of the special status of Kashmir was beneficial for them. Their voices being allowed to exist without coercive action only when they are congruent to the state’s narrative is anti-empowerment. The real emancipation of marginalised identities lies in formulating policies with their participation and in listening to their voices, even if they, at the cost of discomfort to the Indian state, collectively echo azaadi. That is the only future that should be envisioned.

References

- Bhat, A (21 August 2019). ‘Kashmir women are the biggest victims of this inhumane siege’. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/women-biggest-victims-inhumane-siege-190820122327902.html

- Siddiqui, Z (8th August 2019). ‘Indian men who see new policy as chance to marry Kashmiri women accused of chauvinism’. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-women/indian-men-who-see-new-policy-as-chance-to-marry-kashmiri-women-accused-of-chauvinism-idUSKCN1UY104

- BBC News (11th September 2019). ‘India’s Kashmir move: Two perspectives’. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-49521419

- Shukla, S (16th November 2019). ‘Homophobic, misogynist and a bigot’ – meet Jair Bolsonaro, India’s Republic Day chief guest’. ThePrint. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/world/homophobic-misogynist-and-a-bigot-meet-jair-bolsonaro-indias-republic-day-chief-guest/321549/

- Batool, E (2018). ‘Dimensions of Sexual Violence and Patriarchy in a Militarised State’. Economic and Political Weekly. 53, 47.

- Press Trust of India (22nd January 2019). ‘J&K women marrying non-natives don’t lose residency rights: Expert’. Business Standard. Retrieved from https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/j-k-women-marrying-non-natives-don-t-lose-residency-rights-expert-119012201079_1.html

- Kaul, A (13th August 2017). ‘My Kashmir is “Almost Matriarchal” – Our Inheritance Laws Are Proof’. thequint. Retrieved from https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/rights-of-female-state-subjects-of-kashmir

- Jankar Singh v. State And Ors. Jammu & Kashmir High Court (1995). 1995 CriLJ 3263

- Outlook Bureau (7th September 2018). ‘Supreme Court Judgment On Section 377 Applicable To J&K, Say Legal Experts’. Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/sc-judgment-on-377-applicable-to-jk/316214

- Nabi, S (20th February 2020). ‘‘Article 370 Scrapped At Wrong Time’: Plight Of Kashmiri Transgenders Post-Abrogation’. The Logical Indian. Retrieved from https://thelogicalindian.com/exclusive/transgenders-kashmir-article-370-19850

- Sofi, Z (13th August 2019). ‘In a Ravaged Kashmir, One Woman’s Fight to Give Birth. TheWire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/rights/kashmir-article-370-srinagar-curfew-lal-ded-hospital

- Watali, N. A (9th October 2019). ‘Women Overlooked in Kashmir’s Resistance against India’s iron-fisted Policy’. TRTWorld. Retrieved from https://www.trtworld.com/perspectives/women-overlooked-in-kashmir-s-resistance-against-india-s-iron-fisted-policy-30463

- Zargar, A (30th September 2019). ‘Kashmir: Women in Rainawari Accuse Local Police of Unleashing ‘Reign of Terror’’. Newsclick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/Kashmir-Women-Rainawari-Accuse-Local-Police-Unleashing-Reign-Terror

- Rehbar, Q & Zahra, M (26th November 2019). ‘This is how women are suffering under India’s crackdown’. TRTWorld. Retrieved from https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/this-is-how-women-are-suffering-under-india-s-kashmir-crackdown-31692

- FP Staff (20th April 2020). ‘Masrat Zahra booked under UAPA: Kashmiri photojournalist’s work focussed mostly on women, conflict reporting in Valley’. FirstPost. Retrieved from https://www.firstpost.com/india/masrat-zahra-booked-under-uapa-kashmiri-photojournalists-work-focussed-mostly-on-women-conflict-reporting-in-valley-8278721.html

- IPDK & APDP (2015). Structures of Violence: The Indian State in Jammu and Kashmir. The International Peoples’ Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Indian-Administered Kashmir [IPTK] and the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons [APDP].

- JKCCS (1st July 2020). ‘Bi-annual HR Review: 229 killings, 107 CASO’s, 55 internet shutdowns, 48 properties destroyed’. Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society. Retrieved from https://jkccs.net/bi-annual-hr-review-229-killings-107-casos-55-internet-shutdowns-48-properties-destroyed/

- Anjum, A (2018). ‘Moving from Impunity to Accountability Women’s Bodies, Identity, and Conflict-related Sexual Violence in Kashmir’. Economic and Political Weekly. 53, 47.

- Zia, A. ‘The Killable Kashmiri and Weaponized Democracy’. ThePolisProject. Retrieved from https://thepolisproject.com/the-killable-kashmiri-and-weaponized-democracy/#.Xww5m20zZ0x

About the Author: Misbah Reshi is from Indian Administered Kashmir. She graduated from St. Stephen’s College and is currently studying law at Campus Law Centre, Faculty of Law, University of Delhi. She has contributed to various human rights reports focusing on minority rights in India and violations in Kashmir.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.