Punitive Childhood

Child Rights Post Abrogation

Malika Galib Shah and Junaid-Ul-Shafi

The valley of Kashmir has been an epicenter of the conflict, primarily between India and Pakistan, for seven decades now. This conflict has been marked by grave human rights violations and humanitarian crises over these decades. While there has been some study on its impact on the economy of the valley, loss of human lives, and to a little extent even the sexual abuse of women, one grave aspect remains barely touched – children in this conflict. Through this paper, the authors aim to examine the impact of siege enforced by the state after the unilateral revocation of the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Constitution on the children of Kashmir. Through this paper, the authors seek to determine its impact on children’s daily lives – from their education to their socialisation; the loss of children’s lives as the aftermath of this decision; as well as the rampant illegal detention in prisons for juveniles as a means of harassment, all of which stands in clear violation of India’s obligation under the Municipal law as well as its obligation under the International Law.

Introduction

August 5, 2019, marks the watershed moment in the history of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir where the Government of India, through a Constitutional amendment, decided to strip the state of its special status that formed the basis of the state’s accession to India. This unilateral abrogation not only resulted in the degradation of the status of J&K from statehood to that of a Union Territory, and hence, directly under Control of the Central Government, but also in the unilateral abrogation of the Constitution of J&K. All this was done without taking into confidence the entire population of the region, the same population that was most affected by this decision.

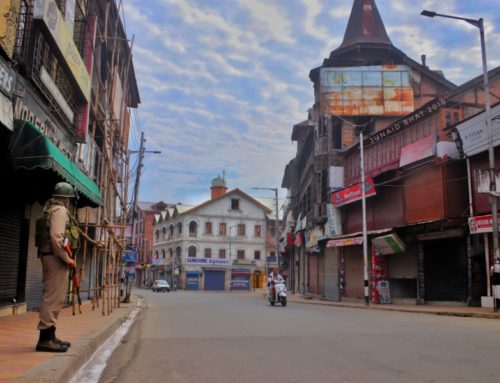

Immediately before this announcement, the entire state was put under a total siege, and a curfew was imposed in this highly militarised region. As a regular modus operandi, all means of communication were shut – landlines, mobile phones, and internet connections, only this time to be the longest a modern-day democracy has ever witnessed. Under a complete communication clampdown and siege, children formed the worst affected victims of this clampdown. The impact being both multi-fold and long term.

Education

Education has been one of the primary casualties in areas of armed conflict, along with the life and liberty of young children. World over, it has been found that the children are the worst sufferers of conflicts whether in a large-scale armed conflict like Syria or Afghanistan or in a conflict encompassing siege and occupation as seen in Palestine and Kashmir.

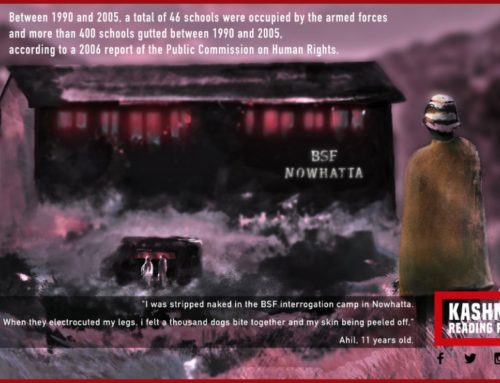

The occupation and destruction of educational institutions and in some places forced closure of these institutions amount to a violation of the basic rights of children protected under International law. The destruction of schools and health infrastructures, along with housing, has a direct effect on schooling and health for exposed populations. According to a World Bank report, economic and social costs of conflict persist for years even after the end of the conflict. The Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) in their flagship report – ‘Education Under Attack’ 2018 revealed that deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on schools, universities, students, and staff are becoming more widespread in conflict situations across the world. Globally, there have been more than 12,700 attacks on education facilities that have harmed over 21,000 students and educators between 2013 and 2017. Such militarisation of educational institutions or spaces in armed conflicts results in reduced school enrolment, high dropout rates, lower educational attainment, poor schooling conditions, and the exploitation of children.

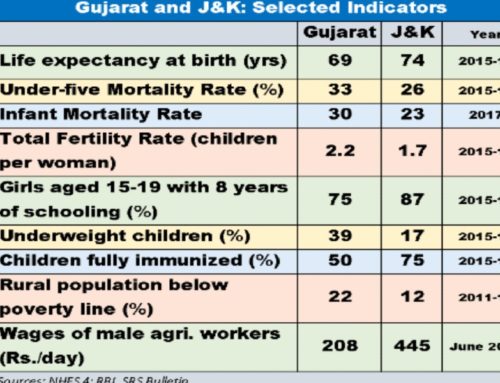

Kashmir and its children have been no exception to these casualties. After the announcement of the abrogation of the Constitution of J&K, including most of the statutes passed by the erstwhile State, all educational institutions including Universities, colleges and, schools were shut down and within months of the siege, a two and a half month-long winter break was declared in all these institutions. Even when the Indian government continued to claim the return of normalcy in the valley, the grassroots reality was very different. All educational institutions remained shut till February 2020. These institutions re-opened partially only for a week when the students were again confined within the four walls of their homes, this time due to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. All educational institutions continue to remain shut even to this date.

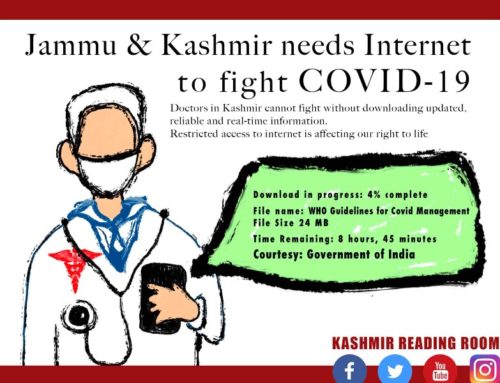

While this kind of a school closure has been the first in India and the world, it has been a regular situation for Kashmiri students. They have had to miss an entire academic year sitting within the confines of their homes. While one may feel that in the present scenario the situation of Kashmiri children is at par with that of the rest of the world, yet there is a stark difference. While India and the rest of the world have taken to online education, the children of Kashmir have no access to the same because of the limited/curtailed 2G internet connectivity available to them.

In the entire region of Jammu and Kashmir, internet connectivity remained shut for almost six months in a row after which only limited 2G internet access was enabled. Despite dedicated efforts of various school authorities for providing online learning, the limited internet connectivity has made it hard to create a conducive learning environment. Moreover, it has confined the right to education to the students of certain affluent schools alone that can afford the kind of infrastructure needed to impart online learning, leaving the rest in a complete state of ignorance and despondency, deprived of their basic right to education. This is worthy to note here that the right to education is well-recognised both nationally as well as internationally.

The Constitution of India, under Article 21A, provides for free and compulsory education of children as a fundamental right. The importance of this right in the Indian Constitution can be gauged from the fact that this right was moved from the position of a non-enforceable Directive Principle in Part IV of the Constitution to the enforceable fundamental right in Part III of the same Constitution through the 86th Constitutional Amendment Act in 2002. Further, the Union government has enacted the Right to Education Act (2009) making it obligatory on the State to ensure free elementary education to every child in the age group of six to fourteen years of age.

At the international level, the right to education has been recognised by several international and regional legal instruments: treaties (conventions, covenants, charters) and also in soft law, such as: general comments, recommendations, declarations, and frameworks for action. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) provides for this right, not only as a right in itself but also as a means to attain human development, and promotion of human rights, tolerance and peace.Similarly, Articles 13 & 14 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Article 24 on the Convention of the Rights of Child (CRC), also provides for the Right to education. The right to education is one of the key principles underpinning the Education 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) adopted by the international community. SDG 4 is rights-based and seeks to ensure the full enjoyment of the right to education as fundamental to achieving sustainable development. However, in the valley of Kashmir, this right stands in clear violation of India’s obligation under its law as well as the International law.

Azaan (name changed), a fifth-class student from Aharbal in Kulgam district has not attended school since August 2019. He misses his daily routine, his studies, and his interaction with his classmates, teachers, and friends. He still is one of the lucky few who has some teaching support at home that allows him to stay in touch with his study routine even while the schools remain closed. In a similar case, Bushra (name changed), a 7th standard student from DPS, Srinagar has been to school only for a week in an entire academic year, like everybody else in the region. Online classes are a struggle for both the teachers and students with limited internet access. A major portion of the class time goes into repeating and re-repeating a paragraph or two as students lack proper internet connection to support their online learning. Frequent lags and disruptions form a regular part of their online learning experience, with little gain at the end of hours of struggle. It is pertinent to mention here that DPS is one of the very few schools that has been able to provide some kind of an online teaching arrangement with its well-established infrastructure. For the majority of the student population, even this kind of limited learning set up remains a distant dream.

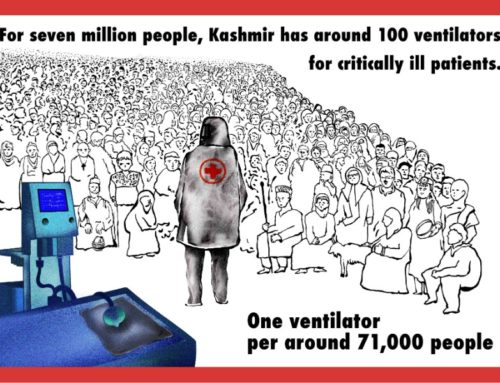

This problem has not been limited to school children alone, but also extends to students enrolled in important professional courses like medicine. Seerat (name changed), an MBBS student hasn’t been able to access the internet to keep herself updated on the latest development in the medical field, especially in the wake of COVID-19 and the fast progressing discoveries and developments in the area. According to her, it takes her hours together to research a simple question on the internet owing to the limited speed. She, like a lot of others in the valley, has been unable to prepare for foreign medical examinations despite having paid a hefty amount for the same. Such courses require an active internet connection to which the students in the valley have no access.

These students stand little chance at excelling with their counterparts in India, leave alone their counterparts from the rest of the world. In a time and age of technological advancement, the students of the valley have forcefully been made technologically handicapped and educationally backward, by the very government that’s supposed to enable human development and personal growth of its people, especially children.

Mental Health

Apart from the high impact on their education, this prolonged siege has also impacted the mental health of the children of Kashmir. With schools closed, streets under curfew, and playgrounds a no-go-area, children have been confined to their homes. They can hardly venture out of their homes amidst sporadic protests, tear gas shelling, and the threat of pellet injuries. The complete suspension of telecommunication services also restricted any chance of connecting to their friends. With little left to do for these children, some of them as young as 8, have taken to street protests shouting slogans for gun culture in Kashmir.This prolonged siege, followed by the COVID pandemic, has also seen frequent instances of violence in the valley. Encounters, leading to civilian deaths and injuries, including children casualties, and destruction of property form part of the daily lives of the people.

These developments have led to a serious impact on the mental and psychological health of these young children in the valley. Locked up in their homes, children have been witnessed to suffer from anxiety and restlessness.Mental health professionals are concerned with an “epidemic of psychological disorder” among the children in the valley. Children form the most vulnerable victims of psychological disorder due to their inability to extract the trauma from their memory which may manifest differently in the later part of their lives, at times hampering the development of brain structure. IMHANS-K has seen around 200 mental health cases in the last 12 months as a result of frequent crackdowns by armed forces in the region. Of these, around 80% belong to pre-adolescence and early adolescence age groups. As part of the ongoing conflict from one episode to another, the situation in Kashmir is unlike any other classic post-traumatic stress disorder and is peculiar to the region. These children are at a higher risk of becoming prey to drug abuse and depression.

Recently the picture of a young three-year-old child sitting on his dead grandfather’s corpse was widely circulated in the media. Exposure to violence at such a young age leaves a long-lasting mental, emotional and physical harm such as extended periods of stress, depression, criminality, etc.Not only their mental health but the physical health of these children are also being adversely affected. Studies have revealed that spending more time inside the house makes children vulnerable to the effects of indoor pollution which can affect their brain development leading to limited development of cognitive abilities.

Illegal Detention and Torture

The young children in Kashmir don’t have to battle mental health and loss of education alone but a large number of these children have been frequently subjected to inhuman treatment by the state paramilitary forces and state machinery. Illegal detention, accompanied by torture, cruel and undignified behaviour has marked the lives of numerous Kashmiri children, again, all against the national and international norms. Children have been victims of illegal detention even before August 5, but after the abrogation of Article 370 such detentions have gained pace, partly as a means to showcase the states’ power against the helpless population of the region, and partly to break down the courage and resilience of the people using humiliation as a vital tool. Children even below the age of 11 have been picked up, detained, and tortured. However, very few cases of illegal detention have been reported due to strict blockade on press and telecommunication in the region.

An 11-year-old boy from the Pampore region in Kashmir was picked up by the forces and illegally detained, without any formal record, between the 5th of August and 11th of August, 2019. In a fact-finding report by All India Democratic Women’s Association, the army has been accused of illegally detaining boys as young as 13 and torturing them for months together. The army officials are also accused of ransoming poor families for the release of their children claiming anywhere between INR 20,000 – 60,000 from the families of these young, tender aged detainees.

In another incident, 5-year-old Muneefa, was badly injured in her right eye after an army jawan deliberately hit her with a stone from his catapult. This incident happened when the young girl was heading home with her uncle. Two teenage boys, aged 14 and 16, were picked up and illegally detained from their residence in Mehjoor Nagar area in Srinagar, on the intervening night of August 19 and 20.

A 17-year-old teenage boy was illegally detained and beaten up with chains at the Soura Police station On August 20, when he was heading to the hospital with food for the relative admitted there. Similarly, a 12-year-old was picked up by the forces, beaten with the butt of a gun, and slapped on the face before being illegally detained in the Safa Kadal Police station lockup. He had gone to get some bread when protests broke out in the area.

In another incident of torture and illegal detention, a 17-year-old boy was picked up and detained on August 6 in a midnight raid by the police at around 1:30 am. According to the teenager, these policemen had their faces covered. They yelled and punched at the young boy before he was thrown inside the police vehicle, with 6 other minors who were picked up similarly. None of these children were presented before any court or sent to any juvenile home. He was illegally detained for 37 days with 15 other minors in a small dark cell with hardly any light. There was a blocked latrine adjacent to the cell which used to stink, as a result of which all of these illegally detained young boys fell ill.

According to the fact-finding report, nearly 13,000 teenagers have been illegally detained after the abrogation of Article 370. However, official figures denote that only 144 young children/ juveniles have been detained in the valley post abrogation, some of whom were kept in observation homes for varying periods as a preventive measure. A 9-year-old boy from Srinagar finds his place in this list of 144 officially accepted illegal detentions. Illegally detained on the 7th of August, the young orphan was kept in the police station for two long days.

In the absence of an FIR or any other formal record of such detentions, it becomes difficult for the families to file a Bail Application before the concerned court. Between August 5 and September 30, 2019, nearly 330 Habeas Corpus petitions have been filed before the concerned Court. Communication blockade, later accompanied by the COVID 19 lockdown, has made it difficult for families to seek justice in such petitions. Out of all the Habeas Corpus petitions filed before the High Court after August 5, 99% of the petitions remain pending.Most of these illegally detained children are lodged in far-flung jails, where they are unfamiliar with the climatic conditions and unbearable heat of the region. This further breaks down these young boys, both mentally and physically.

Deaths

Besides being victims of illegal detention and torture, children of the valley have also been killed in cold-blooded murder post abrogation.

In one of the many incidents, a 15-year-old boy committed suicide after allegedly being assaulted by the army.In another one, a 16-year-old boy, Osaib Altaf, drowned in river Jehlum after allegedly being chased by paramilitary forces on his return from his cricket match. Similarly, the killing of a 4-year-old in an encounter in the valley is another example of the lives Kashmiri children are living in the conflict zone.

Such actions of the government are against the well-established national and international legal principles. These actions by police are an assault on the principles of Fairness and Rule of Law. As a party to the most important Convention dealing with child rights internationally, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), India has consistently underperformed and failed in fulfilling its obligation towards children in the valley of Kashmir. Article 19 of the Convention lays down an obligation on the state to take all appropriate “legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation”. It also provides that such protective measures should provide for the identification, reporting, investigation, and judicial involvement among other prevention techniques.

Article 39 of the CRC further lays down an obligation on its member states to take appropriate measures “to promote physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration of a child victim of any form of neglect, exploitation, or abuse; torture or any other form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; or armed conflict”. Such recovery and reintegration are to be ensured in an “environment which fosters the health, self-respect and dignity of the child’’.Article 37(b) of CRC prohibits the unlawful or arbitrary deprivation of a child’s liberty. All arrests, detention, or imprisonment of children has to be in conformity with the law and as a measure of last resort, for the shortest appropriate period of time.

UN CRC grants 4 sets of rights to every child – Right to survival, which includes the right to life health and good standards of living; Right to protection, which includes the protection of children from exploitation, inhuman treatment, violence, abuses, and also including the right to special protection in critical situations of emergency, civil and armed conflicts; Right to development , which includes the right to education, childhood care, and development, social security and recreation and cultural activities; and Right to Expression, which includes respect for the views of the child, freedom of speech and expression, freedom of thought and conscience, etc.

India’s own Constitution imposes a duty on the State to protect the life and liberty of all its citizens which includes Juveniles. The provisions of Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 and the Jammu and Kashmir Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2013, have also been brazenly violated. These Acts clearly provide for no juvenile to be arrested and put in a regular prison. Instead a whole separate detailed procedure is provided in the legislations for dealing with children in need of care and protection as well as children in conflict with the law.

Even the Supreme Court of India in Re: Exploitation of children in orphanages in the state of Tamil Nadu vs Union of India, directed the Juvenile Justice Boards (JJB) not to be silent spectators to instances of juvenile detention in regular prisons or police lockups. Instead, it cast a duty on the JJBs to ensure that the child is immediately granted bail or sent to an observation home or a place of safety. The highest court of the land reiterated that the Act could not be flouted by anybody, least of all the police.

Despite the legal guarantees, protection, and human rights available to every child both nationally and internationally, the children in Kashmir are deprived of the same. They are living in an environment of fear, humiliation, torture, and rampant illegal detentions and killings. There is a complete absence of juvenile justice machinery in place. All the JJBs and the Child Welfare Committees (CWC), which form an important part of the Juvenile Justice Act, stand abolished, just like the Jammu and Kashmir Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2013.

In the absence of state machinery as important as this, there is little protection available to the children of the valley. Even the extension of India’s Juvenile Justice Act 2015 to the region will only prove detrimental for its children aged 16 and above who can now be tried under the regular criminal justice system. This central JJ Act will make legal what was otherwise being done covertly. It will now legally allow the detention of children aged 16-18 years for heinous offences even if the act involves mere sloganeering in peaceful demonstrations.

As the state continues to conveniently bypass its national and international obligations, it’s this budding generation that is being dispossessed of what they are legally entitled to.

Conclusion

India’s unilateral revocation followed by a complete clampdown on its civilian population has been violative of the basic human rights of its population, especially children. It has also been a deviation from the well-established principles of the Rule of Law. For the last one-year children have been deprived of some of the most valuable and basic human rights like the right to education, and socialisation. They have been living in a black hole, cut off from the entire world, cocooned in a shell of violence and terror. Their social interaction and outdoor activities have gone down to zero – two activities that are of utmost importance to a child’s overall development. With no opportunities to vent their feelings, socialise, and develop, there has been a grave impact on the mental health of these children. Illegal detentions, torture, and death of children form part of the law in the region. Close to a year to the abrogation, there has been little change in the situation of the children of the valley. The most recent incident being that of the three-year-old child sitting on his dead grandfather’s body. Marred by child rights violations, the erstwhile state is yet to have an established juvenile justice machinery in place.

The new Juvenile Justice Law implemented in the region still remains in Statute alone with no on the ground application, except for the detrimental power to hold 16 years old accountable under the regular criminal justice system, when the International Community continues to define every human being under 18 years of age as a child.

There is an urgent need to look at the children’s rights and their violations in Jammu and Kashmir. The perpetrators need to be held accountable for such violations rather than being provided state support. The best interest of the child globally forms the essence of the larger human rights issues and debates across all spectrums. A blind eye to child rights violations and disregard for child rights will only leave an entire generation of illiterate, socially misfit, troubled, and in need of mental health support.

References

- Gettlemen, J and ors (5 August 2019). ‘India Revokes Kashmir’s Special Status, Raising Fears of Unrest’. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/05/world/asia/india-pakistan-kashmir-jammu.html

- Kashmir Monitor (29 October 2019). ‘Addt’l 70k troops to stay put till April 2020’ Kashmir Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.thekashmirmonitor.net/addtl-70k-troops-to-stay-put-till-apr-2020/; also see Outlook Bureau (30 March 2018). ‘Children In J&K Living In Most Militarised Zone Of The World, 318 Killed In Last 15 Years, Says Human Rights Group Report’ Outlook Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/children-in-jk-living-in-most-militarised-zone-of-the-world-318-killed-in-15-yea/310230

- Fareed, R (5 September 2019). ‘Anger and defiance mark one month of Kashmir siege One month since a lockdown was imposed in Kashmir, residents vow to resist New Delhi’s move to scrap its special status’ Aljazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/anger-defiance-mark-month-kashmir-siege-190905060143123.html

- Devakumar,D et al.(2015). ‘Child health in Syria: recognising the lasting effects of warfare on health’. Conflict and health. Vol. 9, pp. 34. DOI :10.1186/s13031-015-0061-6

- Massad, S; Stryker, R; Mansour, S. & Khammash, U. (2018). ‘Rethinking Resilience for Children and Youth in Conflict Zones: The Case of Palestine, Research in Human Development’. 15:3-4, 280-293, DOI: 10.1080/15427609.2018.1502548

- International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War, 27 August 1874, not ratified, 1 American Journal of International Law (1907) Vol.1(supp.),p p.96

- The World Bank Annual Report 2003. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/259381468762619763/pdf/270000PAPER0English0WBAR0vol-01.pdf

- Education Under Attack 2018; A Report By The Global Coalition To Protect Education From Attack.

- The effects of armed conflict on schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Educ Dev. 2012;32(2):341–351 Convention

- Zargar, S (23 May 2020). ‘In Kashmir, school children have barely gone to classes for nine months’. Scroll.in. Retrieved from ://scroll.in/article/962295/in-kashmir-school-children-have-barely-gone-to-classes-for-nine-months.

- PTI (12 May 2020). ‘2G internet services restored in 8 of Kashmir’s 10 districts’. The Economic Times .Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/2g-internet-services-restored-in-8-of-kashmirs-10-districts/articleshow/75687435.cms

- Zargar, S ( 23 May 2020). ‘In Kashmir, school children have barely gone to classes for nine months.’ Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/962295/in-kashmir-school-children-have-barely-gone-to-classes-for-nine-months.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Art 26 (2)

- Gettleman, J (30 September 2019). ’In Kashmir Growing anger and misery’. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/30/world/asia/Kashmir-lockdown-photos.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

- Kashmir caged Fact finding Report also see https://peoplesdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Kashmir-Caged-final-report.pdf

- Yadavar, S and Parvaiz, A (14 September, 2019). ‘Ground Report: Kashmir’s Blackout is triggering a new wave of mental health issues’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/health/kashmir-blackout-report-mental-health; Mathew, A and Ors. (27 September 2019) ‘Childhoods lost in a troubled paradise’. The Hindu. Retrieved from, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/childhoods-lost-in-a-troubled-paradise/article29522893.ece

- Ashiq, P (2 July 2020) ‘Children in Kashmir valley vulnerable to ongoing trauma, say doctors’ The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/children-in-kashmir-valley-vulnerable-to-ongoing-trauma-say-doctors/article31972531.ece

- Husain, A (2 July 2020). ‘Photo of toddler sitting on slain grandpa angers Kashmiris’. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/photo-of-toddler-sitting-on-slain-grandpa-angers-kashmiris/2020/07/02/01268632-bc45-11ea-97c1-6cf116ffe26c_story.html

- https://www.nrf.ac.za/content/effects-violence-children

- Franklin PJ. Indoor air quality and respiratory health of children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2007; 8:281–6

- Shah, M. G (2020). ‘Children of conflict: an analysis of the Jammu and Kashmir Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2013’ Indian Law Review, 4:1, 105-119, DOI: 10.1080/24730580.2019.1703490 Last accessed on 8th of July 2020

- Kashmir Caged also see https://countercurrents.org/2019/08/kashmir-caged-fact-finding-report/

- Ibid.

- Wallen, J (25 September 2019). ‘Young boys tortured in Kashmir clampdown as new figures show 13,000 teenagers arrested’. Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/09/25/young-boys-tortured-kashmir-clampdown-new-figures-show-13000/

- Irfan, S (19 May 2019). ‘The lives behind Kashmir’s Pulitzer-winning photographs’. TRT World. Retrieved from https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/the-lives-behind-kashmir-s-pulitzer-winning-photographs-36451;

- WP (Civil O.) OF 1166 of 2019 before Supreme Court of India ; https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-364417.pdf pg 25-26

- WP (Civil O.) OF 1166 0f 2019 before Supreme Court of India ; https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-364417.pdf pg 27

- WP (Civil O.) OF 1166 of 2019 before Supreme Court of India ; https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-364417.pdf pg 28

- Javeed, A (22 November 2019). ‘Accounts of four minors contradict the Jammu and Kashmir Police’s claims on illegal detentions’. Caravan Magazine. Retrieved from https://caravanmagazine.in/conflict/jammu-kashmir-minor-illegal-detention-police

- TRT World (23 September 2019). ‘Estimated 13,000 boys arrested in Kashmir since India’s crackdown’. TRT World. Retrieved from https://www.trtworld.com/asia/estimated-13-000-boys-arrested-in-kashmir-since-india-s-crackdown-30168

- Ananthakrishnan G, Adil Akhzer, (2 October 2019). ‘144 minors were detained, Jammu and Kashmir admits to top court’. Indian Express . Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/144-minors-were-detained-jk-admits-to-top-court-6046447/.

- Raina, M (7 October 2019). ‘9-year-old out to buy bread beaten, locked up’. Daily Telegraph, Kolkata. Retrieved from https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/kashmir-9-year-old-out-to-buy-bread-beaten-locked-up/cid/1710267

- Vincent, P (31 October 2019). ‘Grim report from Kashmir’. Daily Telegraph Kolkata. Retrieved from https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/grim-report-from-kashmir/cid/1715947

- 99% Habeas Corpus Pleas In J&K Hc Pending Since Aug. Kashmir Times.Retrieved from Http://Www.Kashmirtimes.Com/Newsdet.Aspx?Q=103378

- Yusuf, S (23 March 2020). ‘Bandipora youth shifted back from UP jail’. Greater Kashmir . Retriedved from https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/kashmir/bandipora-youth-shifted-back-from-up-jail/

- Wallen, J. (25 September 2019). ‘Young boys tortured in Kashmir clampdown as new figures show 13,000 teenagers arrested’ Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/09/25/young-boys-tortured-kashmir-clampdown-new-figures-show-13000/

- Ehsan, M (8 August 2019). ‘16-year-old drowns in Jhelum after alleged chase by CRPF personnel’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/16-year-old-drowns-in-jhelum-after-alleged-chase-by-crpf-personnel/story-9oUP4D6bVvBOpdx2QMOzyK.html

- Rehbar, Q (30 June 2020). ‘Kashmir: 4-Year-Old Boy Killed in Cross Firing Between Militants and CRPF’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/rights/kashmir-minor-boy-killed-crossfiring-militants-crpf

- United Nations Treaty Collections. 11 . Convention on the Rights of the Child”. Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=iv-11&chapter=4&lang=en#EndDec

- United Nations Convention on Child Rights Article 19(1)

- United Nations Convention on Child Rights Article 19(2)

- United Nations Convention on Child Rights Article 39

- United Nations Convention on Child Rights Article 37(B)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with Article 49 also see https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx,

- The Constitution of India, Article 21

- Juvenile Justice Act 2015 Chapter V and Chapter VI

- A Child In Conflict With Law Cannot Be Kept In Jail Or Police Lockup Under Any Circumstances: SC . LiveLaw. Retrieved from https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/a-child-in-conflict-with-law-cannot-be-kept-in-jail-or-police-lockup-at-any-circumstances-sc-read-order-152644

- The Jammu and Kashmir Juvenile Justice Act was abrogated along with J&K Constitution.

- The Central Act treats juveniles aged between 16 and 18 accused of heinous offences as adults.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with Article 1 also see https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx,

About the Author: Malika Galib Shah LLM at UCL, London Chevening Scholar, 2017-18

Junaid-ul-Shafi LLM in Law and Development at Azim Premji University, Bangalore

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.