Indian Judiciary’s Apathy to Habeas Corpus Petitions of Kashmiris

Gayathree Devi KT and Sameer Rashid Bhat

Introduction

After hitting its lowest ebb in ADM Jabalpur during the Emergency, the Supreme Court of India (hereinafter, referred to as the Court) reinvented itself as a protector of fundamental rights. Scholars like Ackerman and Mate characterize the case-law of the post-emergency Court as a mark of its commitment to be the ‘supreme guardian of the Indian Constitution’. While this characterisation may arguably be true for mainland India, what is clear is that for the people of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), the Court is anything but a protector or a guardian. For instance, take the Kashmir Lockdown case of January 2020, in which the Court, after repeated deferrals, returned no finding on the legality of the blanket internet and communication lockdown in Kashmir. Instead, it chose to leave it to the government to ‘review’ its decision, in what can only be termed as an abdication of its protector or guardian role. As though that was not enough, when faced with this question again in the Kashmir 4G Internet case after five agonizing months, the Court had no qualms reiterating its original deferential stance.

But the Court’s most egregious renunciation of its role as a protector till now is reflected in how it has been dealing with Habeas Corpus petitions of Kashmiri detenus post August 2019. In a move that reversed the long-standing adjudicatory approach to Habeas Corpus petitions, the Court now relies on a combination of adjournments and rights-stifling extra-constitutional reliefs, as shall be described in the next section. This is eerily reminiscent of the Court’s failure in ADM Jabalpur to hold the executive to account. One might assume that this deference is peculiar to the Indian Supreme Court. However, unsurprisingly, when it comes to J&K, what is true for the Supreme Court holds good even for the High Court of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K HC). The current piece provides a snapshot of these issues and more.

Habeas Corpus: Supreme Court of India

The Constitution of India, under Articles 32 and 226, confers powers on the Supreme Court of India and High Courts, respectively, to issue, inter alia, the writ of Habeas Corpus. ‘Habeas Corpus’ is a Latin phrase that means ‘to have the body’. Put simply, the writ of habeas corpus requires the state to produce the body of the detenu before the court and justify the detention. Therefore, if an individual is illegally detained, any person can approach the Supreme Court (under Article 32) or the High Court (under Article 226) on their behalf for a writ of Habeas Corpus.

That the writ of Habeas Corpus is one of the most fundamental protections guaranteed to an individual against the state and therefore, has priority over all other business of the Court, is established beyond any doubt. Suffice it to say that Habeas Corpus (as the right to move the Court for the enforcement of the fundamental right to life and liberty) cannot be suspended even during an emergency.

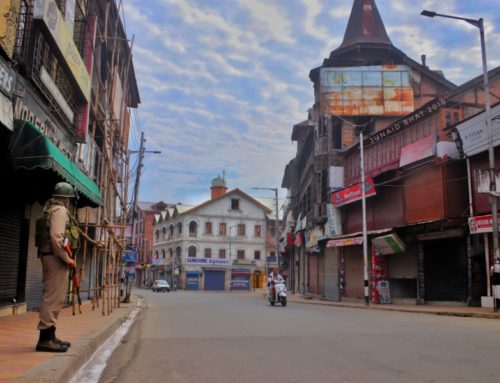

In August 2019, the decision to abolish the special status of J&K was accompanied by the illegal arrests or detentions of thousands of Kashmiris, including activists, businesspersons, leaders from the pro-Indian mainstream political parties, lawyers, journalists and alleged participants in violent protests. Naturally, several Habeas Corpus petitions were filed by the friends, relatives and colleagues of the detenus both in the Supreme Court and the J&K HC. The judicial responses to these petitions encapsulate the failure of Indian Constitutional courts to check executive aggrandizement.

We begin with the first Habeas Corpus petitions that the Supreme Court considered post August 2019. Mohammad Aleem Syed, a law graduate from Jamia Millia Islamia, approached the Court on August 9, 2019 because he could not contact his parents in J&K since August 4. 19 days later, the Court addressed his petition in a peculiar fashion. Instead of asking the government to produce his parents before the judges, it granted Syed ‘permission’ to travel to J&K, visit his parents and after ensuring their well-being, report back to the Court. It is unclear why a court-administered permit raj had crept into Habeas Corpus petitions, but it was a clear indication that the big boss was watching. It is unsurprising therefore that Syed reported back on his visit with this plea: ‘I want to live a quiet and uneventful life.’

Syed’s petition was considered alongside the one filed by Sitaram Yechury of the Communist Party of India challenging the detention of Kashmiri politician and the party’s general secretary Mohammed Yousuf Tarigami. The Court once again responded to Yechury’s Habeas Corpus petition by ‘allowing’ him to meet Tarigami in the place of his detention, instead of asking the government to produce the ‘bodies’ before the courtroom. Crucially, the ‘permit’ given to Yechury came with the following caveats:

On due consideration, we permit the petitioner to travel to Jammu & Kashmir for the aforesaid purpose and for no other purpose. We make it clear that if the petitioner is found to be indulging in any other act, omission or commission save and except what has been indicated above i.e. to meet his friend and colleague party member and to enquire about his welfare and health condition, it will be construed to be a violation of this Court’s order.

In neither of these two petitions did the Court discuss the merits of the petition, or even issue a notice to the Centre questioning the detentions. Although in light of its earlier precedents, in the normal course, the Court should have assessed the legality of the detention as on the date on which the application was made to the Court, it did not venture into the legality of the detention at all and simply ordered that the petitioners were free to meet the detenus at the place of detention. This marked a significant departure in the Court’s approach in the wrong direction for it defeated the purpose of Habeas Corpus petitions to challenge the legal validity of the detentions.

Another case worth considering is the detention of Farooq Abdullah, a mainstream Kashmiri politician, sitting Member of Parliament at the time of his detention, and a former Chief Minister. On September 11, 2019, Rajya Sabha MP Vaiko filed a Habeas Corpus petition challenging Abdullah’s detention. The Court issued a notice to the government 5 days later, on September 16. Although Abdullah was originally detained under Section 107 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), which allows the executive magistrate to detain on grounds of public order and tranquility, curiously, hours before the September 16, hearing before the Supreme Court, Abdullah was charged under the Public Safety Act 1978 (PSA). PSA detention orders can be challenged before the government within 10 days, before approaching the J&K HC.

One would assume that in line with the AK Gopalan precedent, the Supreme Court would have nonetheless considered the legality of Abdullah’s detention as on September 11, the date on which the application was filed. However, in a strange turn of events, the then Chief Justice, Ranjan Gogoi, held on September, 16 that ‘nothing survives’ in the Habeas Corpus petition since PSA charges were brought against Abdullah. The Court appeared unperturbed by the underhanded manner in which the government slipped in PSA charges to block Vaiko’s petition, and also had no regard whatsoever to its own precedents on Habeas Corpus.

The way the Court dealt with petitions concerning the detention of the then Chief Minister of J&K, Mehbooba Mufti, also borders on the problematic. On September 5, Mufti’s daughter Sana Iltija Mufti filed a petition (not Habeas Corpus) seeking the Court’s permission to visit her mother in Kashmir. It is telling that the Court was concerned more about curbing her free movement in Srinagar, absurdly questioning her motivations behind wanting to move freely in Srinagar when it’s ‘cold’. The Court’s response to the Habeas Corpus petition filed by Iltija Mufti on February 5, 2020 has also been less than satisfactory, because it was marred by delays. Although the petition was filed on February 5, the notice was issued only on February 25. The petition was subsequently posted for hearing on March 18, 2020, but not taken up since due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the meantime, on May 5, 2020, Mufti’s detention was extended by 3 months. What is also perturbing is the fact that the Supreme Court required Iltija Mufti to give an undertaking to the effect that she has not filed ‘any other petition before another judicial forum, including the high court, challenging the detention of her mother.’ Once again, this reflects a disregard for precedents – in this, precedents on the application of res judicata in Habeas Corpus petitions. As held by the Supreme Court as early as in 1967, a Habeas Corpus petition under Article 32 would not be barred on the principle of res judicata if a petition for a similar writ under Article 226 of the Constitution before a High Court has been decided.

Yet another relevant case is the Habeas Corpus petition filed by Sara Abdullah Pilot, sister of former J&K chief minister Omar Abdullah, before the Supreme Court, challenging his PSA detention. Like his father, Omar Abdullah was also originally detained under Section 107 of the CrPC. However, on February 4, 2020, he was freshly charged and detained under the PSA. Pilot challenged this on February 10, and the Supreme Court issued a notice to the government on February 14, 2020. However, when it set March 2, 2020 as the date for hearing and Abdullah’s lawyers sought a sooner hearing, Justice Arun Mishra’s remark that since Abdullah already waited for so long, waiting for 15 more days should not make a difference, perfectly captures the Supreme Court’s laidback and insensitive attitude towards the post-August 2019 detentions in Kashmir. Further, curiously, Omar Abdullah was released from detention on March 24, 2020. It is unclear what suddenly inspired the government’s confidence in Omar’s ability to restrain his ‘radical ideology’ it complained of barely one month ago – if anything, it hints at the government’s interest mala fides in detaining Kashmiri politicians.

Habeas Corpus: Jammu & Kashmir High Court

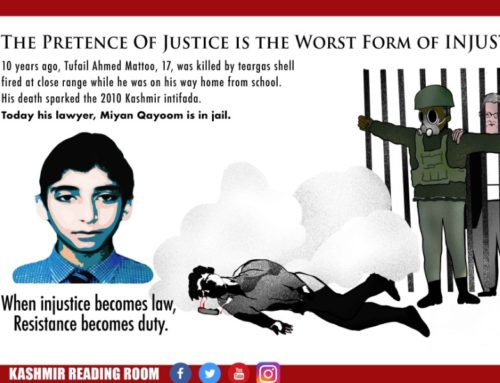

In relation to the consideration of Habeas Corpus petitions by the High Court of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K HC), the case of Mian Abdul Qayoom, the president of the Kashmir Bar Association, is significant. Qayoom was detained on August 5, 2019, charged under the PSA and moved from one jail to another during which his health steadily deteriorated. Yet, the J&K HC took 9 long months only to dismiss his Habeas Corpus petition and uphold his detention. In February, the single-judge bench that rejected his petition observed, strangely enough, that a court is not the ‘proper forum to scrutinise the merits of administrative decisions to detain a person’. In what can only be regarded as the unbecoming of a constitutional court responsible for enforcing fundamental rights, the J&K HC justified the reliance of preventive detention under PSA on suspicion and not proof, and refused to objectively assess the legality of the detention. In another appalling disregard for human rights, particularly the right to freedom of thought, the J&K HC rejected Qayoom’s appeal of the single-judge bench’s decision by asking him to shun ‘secessionist’ ideology.

Quite unsurprisingly, the appeal against the J&K HC’s order before the Supreme Court was adjourned at its last hearing on July 15, 2020. The Court gave the Centre more time to respond regarding the reasons for prolonging detention, even as Qayoom’s health continues to deteriorate. It is telling that almost a year after the detentions, the Courts are still giving time to the government to ‘respond’ although the norm is that Habeas Corpus petitions must be decided immediately or at the earliest. In any case, the J&K HC’s unwillingness or inability to actively secure human rights is evident from the fact the Court has not even decided 1% of the 600 Habeas Corpus petitions filed before it since August 6, 2019.

Conclusion

As we write this piece, news about more adjournments of Habeas Corpus petitions is making it to the headlines. The Supreme Court just adjourned the Habeas Corpus petition filed against the detention of Congress leader Saifuddin Soz, who, like many others, has been under detention since the fateful day of August 5, 2019. Soz, as claimed in the petition filed by his wife, is yet to be informed of his grounds of detention. It’s clearer than ever before that when it comes to J&K and its people, Indian courts find their hands tied by the binding precedents of delay, evasion, abdication and justification. Can the Constitutional Courts in India ever step up to their role of protecting human rights, instead of validating executive aggrandizement and political ideology? If their apathy to Habeas Corpus petitions of Kashmiris is any indication, the answer is a clear no.

References

- ADM Jabalpur v Shivkant Shukla, (1976) 2 SCC 521.

- Neuborne, B (2003). ‘The Supreme Court of India’. International Journal of Constitutional Law. 1(3) 476, 494.

- Ackerman, B (2019). Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of Law 73.

- Mate, M (2018). ‘Constitutional Erosion and the Challenge to Secular Democracy in India’. In Mark Graber, Sanford Levinson, Mark Tushnet (eds). Constitutional Democracy in Crisis?

- Anuradha Bhasin v Union of India & Ors, Writ Petition (Civil) No 1031/2019.

- Foundation for Media Professionals v UT of J&K & Anr, (2020) SCC Online SC 453.

- Noorani, A. G (25 October 2019). ‘Habeas Corpus Law: A Sorry Decline’. Frontline. Retrieved from https://frontline.thehindu.com/cover-story/article29604480.ece

- ADM Jabalpur (n 1) (dissenting opinion of Khanna, J).

- AFP (18 August 2019). ‘About 4,000 people arrested in Kashmir since August 5: govt sources to AFP’. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/about-4000-people-arrested-in-kashmir-since-august-5-govt-sources-to-afp/article29126566.ece

- Mohammad Aleem Syed v Union of India, Writ Petition (Criminal) No 225/2019.

- Sinha, B (26 June 2020). ‘All about the Kashmir petitions and Supreme Court responses.’ Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/all-about-the-kashmir-petitions-and-supreme-court-responses/story-yDTcrHFosyEYKAWNOPOevO.html

- Sitaram Yechury v Union of India, Writ Petition (Criminal) No 229/2019.

- AK Gopalan v Government of India, AIR 1966 SC 816.

- (11 September 2019). ‘Produce Farooq Abdullah in court, Vaiko files plea in Supreme Court’. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/vaiko-moves-sc-to-produce-farooq-abdullah-in-court-and-set-him-free/article29392304.ece

- Rajagopal, K (30 September 2019). ‘SC refuses to further entertain plea by Vaiko seeking information on Farooq Abdullah’. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sc-refuses-to-further-entertain-plea-by-vaiko-seeking-information-on-farooq-abdullah/article29555350.ece

- PTI (26 February 2020). ‘SC issues notice to J&K on plea challenging ex-CM Mehbooba Mufti’s detention under PSA’. The New Indian Express. Retrieved from https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/feb/26/sc-issues-notice-to-jk-on-plea-challenging-ex-cm-mehbooba-muftis-detention-under-psa-2108782.html

- Ghulam Sarwar v Union of India and Ors, AIR 1967 SC 1335.

- Haidar, S (10 February 2020). ‘Omar’s sister challenges PSA charge against him in SC’. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/omar-abdullahs-sister-moves-sc-challenging-his-detention-under-psa/article30780833.ece

- F P Staff (14 February 2020). ‘Omar Abdullah’s detention case: SC sends notice to Jammu and Kashmir admin on sister’s plea challenging PSA charges’ First Post . Retrieved from https://www.firstpost.com/india/omar-abdullahs-detention-case-sc-sends-notice-to-jammu-and-kashmir-admin-on-sisters-plea-challenging-psa-charges-8041201.html

- Ashiq, P (10 February 2020). ‘Omar Abdullah used politics to cover his radical ideology: Public Safety Act dossier’. The Hindu . Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/omar-abdullah-used-politics-to-cover-his-radical-ideology-public-safety-act-dossier/article30778476.ece

- Ganaai, N (7 February 2020). ‘Day After Omar, Mehbooba Booked Under PSA, J&K HC Says “Preventive Detention Not Punitive”’. Outlook India. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-preventive-detention-not-punitive-jk-high-court-dismisses-bar-presidents-plea-for-release/346927 . For more on how the PSA violates human rights, see Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Update of the Situation of Human Rights in Indian-Administered Kashmir and Pakistan-Administered Kashmir from May 2018 to April 2019’ (8 July 2019) https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/IN/KashmirUpdateReport_8July2019.pdf ; ADM Jabalpur (n 1) (dissenting opinion of Khanna, J).

- Ahmad, M (29 May 2020). ‘Prove You “Shunned Separatist Ideology”: J&K HC Upholds Senior Lawyer’s PSA Detention’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/law/jammu-kashmir-mian-abdul-qayoom-psa

- Roy, R (16 July 2020). ‘SC Adjourns Habeas Corpus Plea of Octogenarian Congress Leader Prof. Saifuddin Soz’. Live Law. Retrieved from https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/sc-adjourns-habeas-corpus-plea-of-octogenarian-congress-leader-prof-saifuddin-soz-160004

- Mandhani, A (28 June 2020). ‘99% habeas corpus pleas filed in J&K since Article 370 move are pending. HC Bar tells CJI’. The Print. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/judiciary/99-habeas-corpus-pleas-filed-in-jk-since-article-370-move-are-pending-hc-bar-tells-cji/450281/

- Supra note 180

About the Author: Sameer Rashid Bhat is a 2018 Rhodes Scholar from Kashmir (India) and an incoming PhD candidate at the University of Oxford where he is currently reading for the MSc in Global Governance and Diplomacy. In 2019, Sameer completed the Master of Public Policy (MPP) with a distinction from Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. Prior to Oxford, he obtained an undergraduate degree in law from Gujarat National Law University, India. Sameer is qualified to practice as a lawyer in India.

Gayathree Devi KT is an MPhil candidate in Public International Law at the University of Oxford where she is researching State responsibility for human rights violations in contested territories. She is the HSA Advocates Law Scholar at the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development, Somerville College. In 2019, Gayathree obtained the Bachelor of Civil Law (BCL) degree with distinction from Oxford. Before coming to Oxford, she completed BA.LLB (Hons) at Gujarat National Law University, India and is qualified to practice law in India.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.