Detention of Freedom, Thought and Expression through the Public Safety Act

Saaqib Amin Parray

Administrative Detention

Administrative detention laws override ordinary judicial processes and suspend all protections envisaged including the right to fair trial. Fair trial, a necessary ingredient of criminal jurisprudence, is an inalienable right of an individual which demonstrates spirit of right to life and personal liberty. A preventive detention law usurps these rights and an individual can be detained without trial on the basis of suspicion.

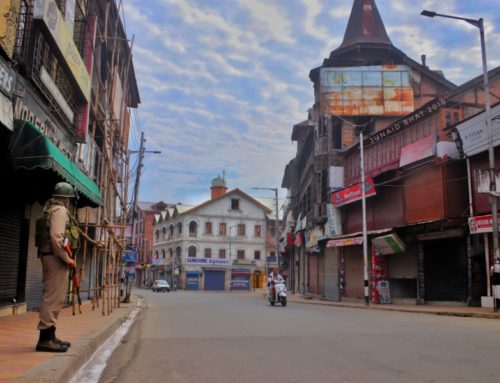

Preventive detention laws have been used to detain thousands of people of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) resisting the control of Indian state. Detentions without trial have been used as a weapon of oppression and individuals are detained for supporting the cause for independence or resolution of Kashmir issue in accordance with U.N. resolutions. Since inception of detention laws, lawyers, journalist’s political activists and others have been detained on a daily basis.

In its 2010 report, Amnesty International observed that the J&K High Court Bar Association (JKSCBA) plays an important role in challenging a large number of detention orders, undertaking jail visits and more generally taking up cases of human rights violations. In this light, the post – August 5, 2019 detention of the President of JKHCBA and other members of bar association appears to be an attempt to intimidate the lawyers. The United Nations (UN) working group on enforced or involuntary disappearances jointly with three other UN special procedures mechanisms has sent an intervention letter to the government of India in July 2010 regarding the arrests and detentions of lawyers of the Bar Association. In 2019, the UK Bar Council and the UK Bar Human Rights Committee sent a joint letter to India’s Prime Minister reminding him of India’s international commitments considering the arrests of lawyers in Kashmir.

Public Safety Act, J&K

The Public Safety Act (PSA) enables the authorities to order preventive detention of a person whose activities it apprehends would either pose threat to the security of the state, or to the public order. In a situation of ‘threat to state/national security’, a person can be detained for two years and for public order the detention can be extended up to one year. The detainee is not produced before any court of law in this duration and the allegations leveled against him are not made subject to judicial review.

Section 8 of the Act envisages the powers for detention, the only requirement for permitting detention under the Act is mere ‘satisfaction of the detaining authority’. In practice, these detention orders are passed based on the orders of the Home Department and in many cases the dossiers are drafted in advance to suppress any political dissent.

This article discusses a few cases out of the hundreds of pending detentions cases in J&K –

Detention of Mian Qayoom under Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978

Mian Abdul Qayoom an eminent lawyer and President Kashmir Bar Association was arrested during the intervening night of August 4 & 5, 2019 under section 107/151 criminal procedure code and on August 7, 2019 an order of detention was passed detaining him under J&K Public Safety Act. The contents of grounds of detention demonstrate the vagueness and uncertainty of allegations leveled against Mr. Qayoom.

Grounds of Detention of Mian Qayoom

The first ground of detention accuses Mr. Qayoom of being a staunch supporter of secessionist ideology and his belief that J&K is a disputed territory. It is pertinent to mention that all accusations have been made without mentioning any dates or events, and only tangible reference is made to the First Information Reports (FIRs) registered against him in 2008 and 2010.

The grounds of detention are filled with sweeping statements without any reference to individual acts of the detainee that have compelled the authorities to detain him. One of the reasons for detaining reads:

“In view of various decisions taken by Union of India on 5th of August, there is every likelihood that the subject will instigate the general public…”

The grounds of detention itself reflect that he was under custody, at the time of passing of detention orders. Section 107 and 151 Cr.P.C. provides for preventive measures and empowers a police officer to arrest a person apprehending a cognizable offence, breach of peace and public tranquility. In addition to this, the FIRs relied on by the detaining authority reflects offences under Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) wherein a person can be detained without warrant from a court of law. The reason people are detained under preventive detention laws when there is enough scope for arresting them under ordinary law is that under preventive laws a detune has no remedy of judicial review, no right to seek bail and the allegations can stand without proof.

Demonstrable Lawlessness

This is a classical case where the lawlessness of preventive detention laws is explicitly demonstrable. As Mr. Qayoom was already under custody, a question can be raised on the need for putting him under preventive detention under the PSA. The reason that such methods are employed is that under ordinary law, every arrested person has a right to fair trial and given the indefinite and ambiguous allegations, the state will find it difficult to prove the accusations. However, under PSA, the only remedy available to a detainee is to file a Habeas Corpus petition in the High Court. Here too, the detainee cannot challenge the allegations made against him, and can only challenge the detention order on procedural violations envisaged under the Public Safety Act, given that limited judicial review is available.

Mr. Qayoom challenged his detention order before the High Court and the grounds of challenge include non-supply of material, the FIRs relied upon by detaining authority dates back to 2008 and 2010, that the detention is passed on merely on the basis of Mr. Qayoom’s questioning by police in 2008 and 2010 and the grounds of detention are vague, indefinite, uncertain and ambiguous. While hearing the petition, the Court held in para 25 of the judgment that the grounds are ‘clumsy’ but upheld the detention relying on FIRs registered in the year 2008 and 2010, notwithstanding the fact that it was brought to the notice of the Court that he was previously detained in 2010 regarding the same FIRs.

Mr. Qayoom’s case is demonstrable of the collusion of interest – how the Courts come to the rescue of administrative authorities in cases related to preventive detention. In its judgment dated May 28, 2020, the High Court not only upheld the detention but also travelled beyond its jurisdiction by upholding the detention based on the ‘ideology’ of a person.

Section 8 of PSA provides for detention of a person who can act in breach of peace and not for a thought or inner manifestation of a person can be made based on passing orders under the Act. While responding to the argument that the FIRs relied upon by the detaining authority are of the year 2010, the court took into consideration the reports from the police which were never provided to the detainee. The court observed in para 48 of the judgment:

“Having considered the matter, we may say that an ideology of the nature reflected in the FIR and alleged against the detainee herein is like a volcano………when it comes to propensity of an ideology of the nature reflected in the FIRs supported by the intelligence reports we have gone through, we are convinced that it sub serves the latent motive to thrive on public order.”

Detention of Masarat Alam Bhat

Another case under the PSA is the detention of Masarat Alam Bhat (21), a political activist, who was detained between 1990 and 2005 for nine years without trial and is presently serving his 37th detention. In one of the judgments (2015), quashing his detention, the court recorded that the detenu for the last two and half decades, except for brief intervals, has been placed under detention.

Detention order dated December 11 was set aside on June 10, 2011. Order dated August 4, 2011 was quashed on December 23, 2011. Order dated December 30, 2011 was set aside on June 2, 2012. And the order dated August 3, 2012 was quashed on October 19, 2012. Another order was passed on October 30, 2012 and the same was challenged before Supreme Court, the order was revoked on March 18, 2013 but he was continuously under custody till January 8, 2014 when a fresh detention order was passed. The court while referring to the Supreme Court judgment in A.K. Roy vs Union of India (1982) observed repeated detention orders, offends the spirit of Article 21.

The failure of courts to get their orders implemented results in further victimization of persons held under preventive detention laws. The practice of re-arresting detainees is very prevalent and that is done either on the ground of frivolous FIRs or by passing of fresh detention orders one after another. This is done to keep persons continuously under detention without trial.

The procedural technicalities create more difficulty in getting orders quashed. On filing of a Habeas Corpus petition, the court grants four weeks’ time to the state for filing reply which is often extended by another four weeks. The High Court Case Flow Management Rules, 2010, provides that in Habeas Corpus cases (detention cases) the court should give only 48 hours’ notice for filing reply and a detention case shall be decided within fifteen days. Every case takes at least three to four months for final hearing and in a number of cases, with the objective to frustrate court proceedings, the state authorities revoke the order of detention only to issue a fresh one later. This practice sets the clock back and the detainee has to file another petition to challenge the fresh order. This fact is evident from Masrat Alam Bhat’s case, he challenged his detention dated October 30, 2012 before Supreme Court, which was revoked on March 18, 2013, turning his petition infructuous only to pass a fresh detention order. The delay in hearing the Habeas Corpus petitions by the courts further adds to the misery of the detainees.

Detention of Sabzar Ahmed Naik

Sabzar Ahmad Naik was first arrested in first week of January 2019 under FIR 65/2018 and was detained on February 27, 2019. Petition challenging detention order was filed on March 9, 2019, to which a reply was filed by the state on May 3, 2019. It is July 2020, and the case has not been decided yet. The grounds of detention are vague, indefinite, without any mention of dates and ambiguous. Five FIRs were registered against Sabzar in the year 2018, with the allegation of stone pelting. The detaining authority has squarely relied on these older FIRs while passing detention order in 2019.

It is noteworthy that Sabzar Ahmad was already under police custody when his detention order dated February 6, 2019 was issued. Surprisingly, the grounds of detention are the same and everyone is labeled as a stone pelter or Over Ground Worker (OGW) of some underground group. Records in this case reveal that the detention order was quashed on May 30, 2019. In this case, the court took four months to hear a petition finally, and even after quashing the detention order he was not released and is still under custody.

Grounds of detention of Sabzar Ahmed Naik

The first ground of detention states-

“This mental setup to achieve freedom from the union of India and merge the state of J&K with Pakistan through violent means has been augmented by the unscrupulous elements who dream of cessation of J&K state from India.”

The next ground for detention states-

“Whereas the Sr. Superintendent of police Shopian further reports that it is his considered opinion based on inputs from various field formations that the prevailing militancy scenario and facts obtained on the ground are not conducive enough for you to be let off…”

These grounds in the detention orders demonstrate the real intent for the arrests. The ‘inputs’ are always used to claim the benefit of section 13(2), which gives protection to the authorities to avoid/deny disclosure of the source and even the details of the information. Notably, even the Court in Mr. Qayooms judgment relied upon these ‘inputs’ while upholding the detention order.

Detention based on FIRs and practice of ‘Open’ FIR

It is especially concerning that in J&K, FIRs are often used as the main ground for detentions. In practice, the police file ‘Open’ FIRs (without naming any accused), then add names of their own choice in the said FIRs as it suits them. The ‘Open’ FIRs are kept languishing and the charge sheets (reports filed by police after investigation to the court under section 173 criminal procedure code) are not filed in those cases for years. In one of the cases, the record reflects that a FIR 278/2016 was registered under UAPA in the year 2016, as an ‘Open’ FIR (FIRs without naming the accused are coined as open FIRs). In 2020, Arshid Ahmad Rather was shown as an accused in the said FIR. He was arrested in April 2020. This practice of open FIRs gives full discretion to the police to add names at their discretion later.

A reminder of the Emergency era

This judgment reminds one of the year 1975 in India, when the courts failed to rescue victims of detention laws and in many cases held that during emergency the government has the power to suspend even the fundamental right to life and liberty. The judgment in Mr. Qayoom’s case has equipped the authorities with more unbridled power to detain persons on the allegation of a particular ideology. The passing of this judgment has injected a firm belief of absolute immunity to the administrative authorities. Its consequences will surely be dangerous.

Juveniles and Preventive Detention

The state authorities also detain young people, with little regard to their age, under the preventive detention laws with impunity. Most of them are labeled as ‘over ground workers’ (OGW-name coined for supporters of militants) and ‘stone-pelters’. The intention of the same is to curb their physical movement. To challenge a detention order, one must file a petition before the High Court. An application under Juvenile Justice Act can be before the Juvenile Justice Board. It takes months to prove that the detainee is below the age of 18 years(minor) and by the time the detention order is quashed, the minor has already spent months in a prison. Juveniles often become victims of open FIRs. The local police arrest minors and their names are then shown in these already registered FIRs.

Not only are the minors detained under ‘open’ FIRs, they are also charged under PSA. There are various tactics of intimidation used by the police. Police officers often bargain with the parents before releasing the minors who are detained. They demand bribes to release the minors, or threaten to charge them under PSA. As a practicing lawyer, I have faced situations when parents of juveniles showed their helplessness to apply for bail under the JJ Act, because the moment a bail application is filed, and another order of detention is passed. In a number of cases, the police intimidate the parents of the juvenile and threaten them against approaching any court or informing anyone about the illegal custody of their kids. This intimidation is a clear warning that an order of detention (under PSA) will follow.

Detention of Ubaid Rashid Mir

Ubaid Rashid Mir S/O Abdul Rashid Mir is presently under preventive detention. He was first arrested by the police in connection with FIRs registered against him. His date of birth is February 6, 1997, and the FIRs stand registered from 2012 (when he was 15 years old). The first FIR registered against him, as shown in the grounds of detention, is FIR 251/2012 and then subsequently in 2013, 2014, 2017 and 2018. Most of the FIRs relied upon by the detaining authority, were registered when he was a minor. He was detained on June 16, 2018 and has been behind bars since then. The order of detention was passed on August 25, 2018 and he was shifted to Kotbalwal jail in Jammu.

This order was quashed by the J&K High Court on December 4, 2018, and soon thereafter, a new detention order was passed on June 6, 2019, which expired on June 25, 2020. This expiry was followed by a yet another detention order No.127/DMS/PSA/2020 dated July 1, 2020. The grounds of detention latest order state activities that he was accused of as a juvenile, no new activities are mentioned to merit yet another detention order. The detention orders are, in practice, issued merely on the whims of the police, this is evident from the very contents of the order. The detaining authority, while a passing fresh detention order against Ubaid, has stated –

“…the activities during the course of your detention have remained highly objectionable and have left no stone unturned in inflicting the blow on the fragile peace environs of district Shopian”.

This indicates how these detention orders are passed- how can a detainee create law and order problems while being in jail? How can he be dangerous to the fragile environs in Kashmir when he is detained in Jammu, 400km away from his home district? As a lawyer I do not have any answers for him.

Detention of Ghulam Jeelani Gatoo

Ghulam Jeelani Gatoo S/O Ab. Aziz Gatoo, serving detention, was arrested in September 2016 in connection with FIRs starting from year 2012. Official records show his date of birth as January 15, 1998. When the first FIR was registered, he was just 14 years old.

Grounds for Detention of Ghulam Jeelani Gatoo

The grounds of detention display a long list of FIRs 173/2012, 64/2014, 70/2014, 76/2014, 77/2014, 83/2014, 84/2014 list goes on up to 2018. His grounds of detention state that he is affiliated to “sung baz-e-shopian” (stone-pelters of Shopian). There is no organization named Sung baz-e-shopion.

The first detention order issued on September 5, 2018 clearly states that most FIRs relied upon by the detaining authority date back when he was a minor. Under the grounds of detention, he is accused of the following-

- being an anti-national

- arranging huge gatherings (in the year 2008, when he was 10 years old)

- inculcating hatred against the government (In 2009 when he was 11 years old)

His Detention order reads:

“…You have been granted Bail in many cases and there is every likelihood that the Honorable court may grant bail to you in other cases also as such it becomes essential to book you under extra ordinary law of PSA-1978”.

The order dated September 5, 2018 was quashed by the court on March 15, 2019. However, he was not released and yet another detention order was passed on May 25, 2019. While the petition challenging the second order is still pending and a new order no. 65/DMS/PSA/2020 was issued on June 27, 2020. The grounds of detention in all these orders of detention are the same; the only difference is the date of detention.

In the detention order of June 27, 2020, the detaining authority has relied on FIR no. 77/2014. The ground of detention reads:

“…As such in order to have maintained the peaceful atmosphere in the entire district Shopian you require to be kept out of circulation...”

This is the real intention behind these detentions, as has succinctly been summarized by the statement of Samuel Varghese Financial Commissioner (Home) Jammu and Kashmir, who told Amnesty in 2010, “We have to keep some people out of circulation”.

Conclusion

The Public Safety Act has been misused and abused by the state ever since it was introduced in Kashmir. The detention orders, as can be seen from the above-mentioned cases, are orders passed without application of mind. The law is designed to give unbridled power to the executive to harass people and deny them any scope of redressal. The ‘revolving-door’ detentions through open FIRs are methods employed to torment the people into subjugation. Post-abrogation, many Kashmiris, including the formerly elected representatives of the state were charged with PSA. Ironically, former Chief Minister of J&K, Farooq Abdulla, whose father introduced this repressive law, was also charged under PSA. Though many people are languishing in jails since August 5, 2019, detaining people under PSA has been an old practice of the Indian administration to ‘keep people out of circulation.’ Though, the de-operationalisation of Article 370 is a major betrayal against the people of Jammu & Kashmir, it does not change much as far as the brutal structural violence perpetrated by the Indian government by means of such oppressive laws.

References

- Amnesty International, “A ‘Lawless Law’ Amnesty 2011 Report on Detentions under the Jammu and Kashmir Public safety Act”, 2011.

- Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act 1978.

- Detention order passed by District Magistrate (Executive) Srinagar, Order No. DMS/PSA/105/2019 dated 07-08-2019.

- LPA NO28/2020 in WP (Crl.) No. 251/2019, The court upholding the detention announced judgment on 28-05-2020.

- Reported in Law Journal, 2015 (4) JKJ 249 [HC] Jammu and Kashmir Judgments.

- Constitution of India Article 21, Right to Life and Personal Liberty

- Rule 8 of Jammu and Kashmir High court Case Flow Management Rules 2010.

- Detention order No. DMS/PSA/2019 dated 27-02-2019

- Detention order Quashed by the High court, Judgment dated 30-05-2019

- A.D.M. Jabalpur vs Shivkant Shukla, AIR 1976 SC 1207

- Habeas Corpus petition No. 248/2018

- Habeas corpus petition No. 220/2019, challenging order of detention dated 25-06-2019, this petition was pending when a fresh order of detention dated 01-07-2020 was issued.

- Habeas corpus petition No. 310/2018, Judgment dated 15-03-2019 Quashing detention order129 / DMS / PSA / 2018

- Habeas corpus petition No. 205/2019 challenging order no. DMS/PSA/19/358-60.

About the Author: Saaqib Amin Parray is an advocate practicing in the High Court of J&K, Srinagar.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.