The Constitutional Courts and Kashmir

Rights dependent on the goodwill of the Courts can never be secure

Saranga Ugalmugle and Clifton D’ Rozario

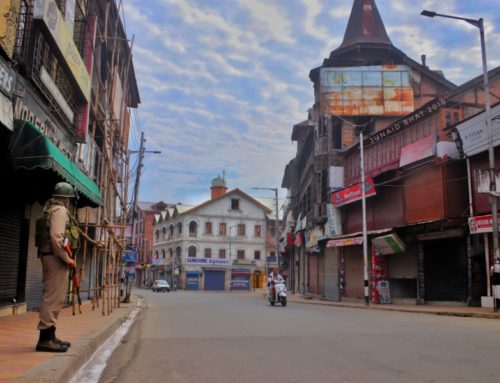

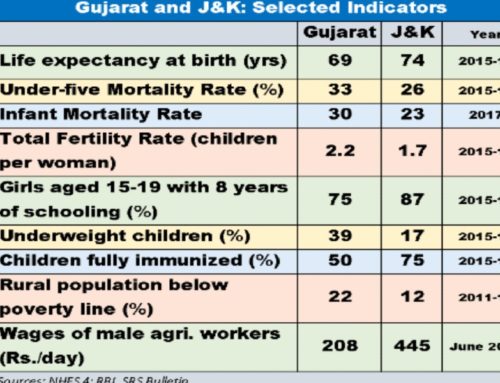

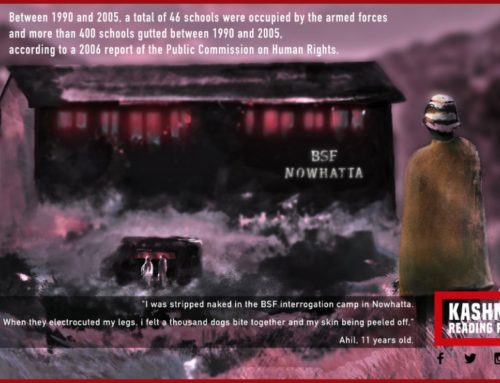

The World Justice Project ranked India in the 69th position in the Rule of Law Index for the year 2020. India’s consistently low ranking is just one indicator of how the Rule of Law is gutted in the country. While this is the situation in India at large, Kashmir, a conflict zone, functions under an almost complete suspension of democracy and the rule of law. Kashmir is known for the impunity with which human rights abuses occur therein- more particularly, by way of illegal detentions of minors as well as adults, numerous cases of alleged rape and torture by the armed forces, and various instances of destruction of homes and properties of families by the J&K Police and the armed forces. Besides these patterns of abuse by the armed forces, the Indian state employs other methods to exert its control over the valley – the arbitrary and indefinite curfews which restrict the right to movement, the communication blockades and blinding of protestors by way of reprisals carried out by the barrels of pellet-firing guns. The people of Kashmir are denied access to justice due to abusive security laws which provide impunity to the armed forces stationed therein and almost nonexistent accountability of the Indian state. To make the situation worse, the judiciary appears to have given carte blanche to the executive by completely abdicating its responsibility, as a protector of the rights of citizens while keeping a check on the excesses of the state.

Kashmir has been under a year-long lockdown since August 5, 2019, initially brought about due to forceful integration of the valley with India, and later extended owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been a slew of litigation from Kashmir since August 2019 with numerous Habeas Corpus petitions being filed in the J&K High Court, and petitions challenging the communication blockade, the violation of rights of children in the valley due to arbitrary detentions and the orders of the amendment to Article 370, etc., in Supreme Court of India. This has been detailed in the report titled ‘Imprisoned Resistance: 5th August and its aftermath’, the fact-finding mission of which the authors of this piece were participants. Here, we look at the status of some of these cases, one year after the abrogation of the special status of J&K, as well as some of the new matters filed before the High Court of J&K and the Supreme Court of India.

An overview of the last few years about how the Constitutional Courts have handled the matters which directly challenge the policy of the current political regime in India shows that there has been judicial evasion which effectively leads to a decision in favour of the government. In this piece, we argue – by briefly analysing some of the important cases concerning Kashmir arising since August 5, 2019 – that there appears to be a similar pattern in which challenges arising from Kashmir have been handled. Despite serious concerns of blatant suspension of fundamental rights of the entire population of the region of Kashmir, the Courts have often delayed and effectively denied justice. Though the solution to the issue of Kashmir’s political status, lies with people’s movements, these experiences with the Constitutional Courts of the land, whether in the form of judicial avoidance, delay or lack of discernible judicial standards to scrutinize claims of security threats, only affirm that the rights, dependent on the goodwill of the courts, can never be secure.

J&K High Court

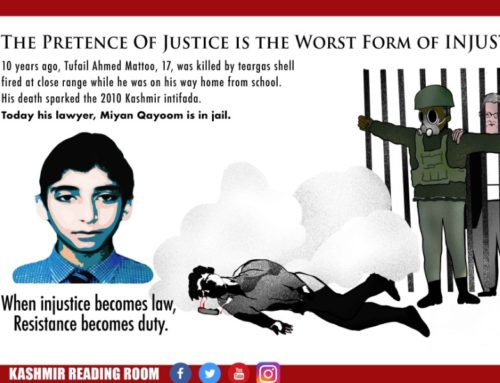

Over 600 Habeas Corpus petitions have been filed before the J&K High Court at Srinagar since August 6, 2019. As per the Rules formulated by the J&K High Court, Habeas Corpus petitions ought to be decided within 14 days of filing the petition. However, the Court appears to have shown no sense of urgency on this front. A representation made the Executive Committee members of the J&K High Court Bar Association, Srinagar dated June 25, 2020 to the Supreme Court of India stated that “since August 5, 2019, nearly 13,000 people from Kashmir valley were arrested u/s 107/151 of the J&K CrPC and thereafter hundreds were booked under PSA and are lodged in various jailed of India.” One of those detained under the Public Safety Act (PSA), includes the J&K Bar Association President, Senior Advocate Mian Abdul Qayoom, who is languishing at the Central Jail, Tihar. The said representation also points out that 99% of the 600 plus Habeas Corpus Petitions filed before the High Court since August 2019 have not yet been decided by it.

On February 7, 2020, a Single Bench of the High Court dismissed a Habeas Corpus Petition which challenged the preventive detention of the aforesaid Advocate Mian Abdul Qayoom. In doing so the Court observed that preventive detention is based on “suspicion or anticipation and not on proof”. Further, the court also stated that the responsibility for security of the State, or maintenance of public order, rests on the Executive. While this proposition cannot be controverted, what happens when the executive has a carte blanche in matters of preventive detention? The court also made a rather absurd comment stating that “A Court is not a proper forum to scrutinize the merits of administrative decisions to detain a person.” This begs the question, what then is a proper forum to impose checks on the administrative decisions?

The said order of dismissal was further challenged before a Division Bench. On May 4, 2020,the Division Bench had to adjourn this matter due to poor internet connectivity. The valley, as is known, has been under a communication blockade for months with no internet connection initially, which was only later restored to 2G connection. When the Supreme Court of India heard a petition seeking restoration of 4G connections in Kashmir, the Central government submitted before it that 4G connections may be used for propagating “modern terrorism”. The lack of fast and efficient connectivity, however, has been hampering access to justice. In any case, eventually, the Division Bench upheld the detention of the 70-year-old ailing Senior Advocate, observing that the ideology professed by Qayoom had an ‘effect’ and ‘potential’ of nurturing a ‘tendency of disturbance in public order’. This bizarre approach of the High Court in deciding whether an order of detention under PSA is valid is baffling, to say the least.

The foregoing narration of how the detention order of a Senior Advocate and President of the Bar Association of the High Court is being handled leaves little to the imagination when the question arises as to how the thousands of other detentions in the valley are being handled, with arguably much less legal support.

The High Court of J&K has decided many other important matters in the last 11 months. In October 2019 itself, the Court declared criminalization of beggary to be unconstitutional and struck down the provisions of the Jammu & Kashmir Prevention of Beggary Act, 1960, and the Jammu & Kashmir Prevention of Beggary Rules, 1964. In April 2020, the HC took Suo moto cognizance of the plight of victims in domestic violence cases amidst lockdown and issued notices seeking action taken report. Further, on April 3, 2020 the Court also passed many directions for protection of Health Workers and sought compliance of Lockdown Guidelines. On March 11, 2020, the J&K HC dismissed a PIL seeking prohibition of the use of pellet guns on civilian protests. The Court stated that “It is manifest that so long as there is violence by unruly mobs, use of force is inevitable” and that whether the use of force is excessive or not, cannot be decided by the Constitutional Court.

The High Court has been proactive in taking up and deciding matters which do not hinder the central government’s brutal control mechanism employed to curb the civil and political rights of the people of the valley. However, when it comes to matters concerning illegal and arbitrary detention orders or the use of blinding pellet guns, the same proactiveness and commitment towards the protection of Constitutional and human rights of citizens against the excesses of the State, seem alarmingly absent.

Supreme Court of India and Kashmir

The challenge to the amendment of Article 370 and other related cases:

At the very outset, it must be pointed out that the numerous cases challenging the de-operationalisation of Article 370 of the Constitution of India and the reorganization of the State of J&K remain pending. The only development in these matters was on the question of whether the cases had to be referred to a larger bench. Incidentally, though some petitioners have asked that the case be sent to a larger bench, most petitioners and the Centre are opposed to it. The judgment was rendered on March 2, 2020 in the case of Shah Faesal, wherein the Court considered whether the issue of the de-operationalisation of Article 370 through the two Presidential Orders would have to be referred to a larger bench on account of two allegedly conflicting decisions of the Court in Sampath Prakash and Prem Nath Kaul. In holding that the two decisions are not in conflict, the 5-judge bench declined to refer the matter to a larger bench. The main issue of the validity of the latest amendment to Article 370 remains sub-judice.

Habeas Corpus cases:

- Insofar as the Habeas Corpus cases are concerned, case of Mohammad Aleem Syed was disposed of on November 19, 2019 because the petitioner sought to withdraw it as infructuous. The petitioner, in that case, had approached the Supreme Court since he was unable to contact his family since August 4, 2019. The Supreme Court, on August 28, 2019, ‘permitted’ him to travel to Kashmir to meet his parents, ensure their welfare and report back to the court. Consequently, Syed visited his parents. On the date of the subsequent hearing on September 5, 2019, he orally stated that he wanted to lead a ‘quiet and uneventful life’ as he handed over an affidavit to the judges in a sealed envelope detailing his visit.

- In another matter, CPM General Secretary, Sitaram Yechury had filed a Habeas Corpus case regarding his party colleague and former MLA Mohammed Yusuf Tarigami and he too was ‘permitted’ to visit Mohammed Yusuf Tarigami and file an affidavit before the Court. The Habeas Corpus case of Sitaram Yechury was last heard on January 28, 2020 wherein the Court directed the Registry to list the matter before an appropriate bench – the matter has not been listed since.

It must be noted that citizens in India do not need a ‘permission’ of the Court to travel. The executive on the other hand, does need to justify to the Court, its actions of detaining the citizens. The writ of Habeas Corpus, which was held to be ‘the first security of civil liberty’, requires the law enforcers to produce a person, who may be untraceable or under detention, before the Court. However, in both these cases, neither was the detenu directed to be produced nor was the State required to justify such detention. Instead, in an order that can only be seen as an abdication of its constitutional duty, the Supreme Court ‘permitted’ the petitioners to travel to Kashmir.

Incidentally, in the case of Sitaram Yechury, while according him such permission, the Supreme Court prohibited Yechury from indulging in any other ‘act, omission or commission’, except – to meet his friend and colleague party member and to enquire about his welfare and health condition. Not satisfied with merely bailing on its Constitutional obligations towards the detenus, the Court went one step forward and, for good measure, thwarted the fundamental rights of the very persons who had approached the Court.

The echoes of the Supreme Court’s moment of infamy in 1976 in the ADM Jabalpur case, where it declared that even the right to life could be suspended during an emergency, were heard when the Court dealt with these cases of Habeas Corpus of Kashmir. Notably, this time around, there isn’t even a declared emergency in Kashmir. While specifically overruling the judgment in ADM Jabalpur in the K.S. Puttaswamy case, the Supreme Court had held that the ADM Jabalpur case, “was an aberration in the constitutional jurisprudence of our country” and it was being overruled with “..the desirability of burying the majority opinion ten fathom deep, with no chance of resurrection.” The grave, however, appears to have been a shallow one – the ‘resurrection’ appears to have occurred sooner than expected.

Violation of child rights:

In our report, we have detailed the instances of widespread violence, arrests, and torture of young boys that came to our attention and also pointed out that a petition on this aspect, of Enakshi Ganguly, was pending before the Supreme Court. After the release of the Report, this case was taken up by the Supreme Court, which on November 5, 2019, directed the Juvenile Justice Committee to send a second report expeditiously. In its final Order dated December 13, 2019, the Court stated that the Juvenile Justice Committee of the High Court made an independent examination that there were no excesses against juveniles. The Court directed that if there are individual cases of illegal detention, the petitioners are at liberty to approach the appropriate forum for redressal. The Court directed the J&K Government to take the services of experts from Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (IMHANS) and the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Centre in Sher-e-Kashmir Hospital to provide help to affected children on the recommendation of the medical officer.

Strikingly, while the matter was being heard before the Supreme Court, the lawyer for the petitioner had argued that “Public Safety Act does not apply to minors. How can they be detained without FIR?”. A judge of the said bench interjected the lawyer and remarked, ““But they were released the same day. Are you aware what 15 year old are capable of doing these days”. The rampant illegal and arbitrary detentions of minors in Kashmir has not been taken as seriously, often with a prejudice that the minors indulge in ‘stone pelting’ on the Indian forces and thus deserve to be detained by the executive. A matter of concern however remains, whether the Constitutional Courts can afford to neglect the obvious illegality and forego the urgent necessity to intervene in issues of such serious violations of fundamental rights and statutory position on detention of minors.

Internet/telephone ban:

Internet and telecommunication services were completely suspended, and a lockdown was imposed in Kashmir in anticipation of protests against the amendment of Article 370 in August 2019. In light of these moves, Anuradha Bhasin, the Executive Editor of Kashmir Times newspaper, moved the Supreme Court seeking to lift the information blockade in Kashmir valley and restore the fundamental rights of its residents. The Court had to decide whether the government had the authority to impose the said lockdown and communication ban; if so, whether the infringing of fundamental rights was necessary? During the hearings, whilst refusing any interim relief, the Court firstly accepted an assurance from the Attorney General that the issue would be settled soon. Secondly, as the order dated September 16, 2019 reveals, the Court acquiesced with the State’s notions of national interest and internal security, marking these as riders even in any decision to restore normal life in Kashmir. Later in the hearing, when the state was asked by the Court to reveal the orders under which the restrictions were imposed, the Solicitor General (SG) claimed that revealing the order to the petitioner would hinder national security. The Court, instead of condemning such lack of transparency of the state, allowed the SG to file an affidavit explaining the reason for such ‘privilege’.

Eventually, after five months of almost complete suspension of communication in the Kashmir valley, the Court delivered its judgment on January 10, 2020. The Apex Court held that an order suspending internet services indefinitely is impermissible, but may be valid for a temporary duration only, adhering to standards of proportionality, subject to judicial review. The court laid down many important principles in the said judgment. Though a fine job of summarising the law on this question was done, the Court refused to decide the fundamental question before it – the constitutionality and legality of the order of internet ban in the valley – and left the decision to be taken by the state. During the intervening period between the filing of this case and its disposal, the people in Kashmir suffered the longest internet shutdown in a democracy.

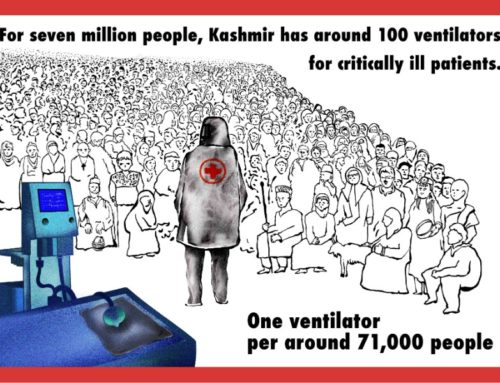

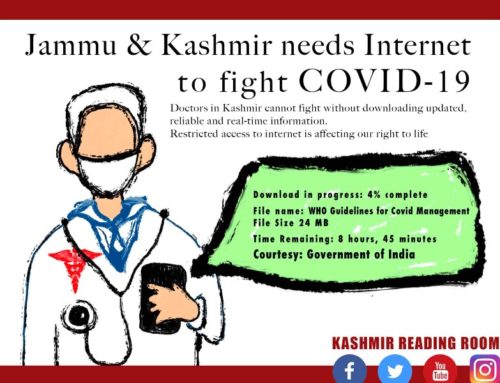

A review committee was eventually set up which led to gradual but partial restoration of communication services in the valley. It was around March 2020, coinciding with the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, that 2G internet was finally made available in Kashmir (but 4G continued to remain banned). This was challenged in the Supreme Court in Foundation for Media Professionals case on the ground that in the existing COVID-19 situation, when there is a national lockdown, the restrictions imposed on the residents of the entire Union Territory of J&K impacts their right to health, right to education, right to business and right to freedom of speech and expression. It was argued by the petitioners therein that access to the internet acquires greater importance under the prevailing circumstances in the country relating to the pandemic since the fulfillment of the right to health is dependent on the availability of effective and speedy internet. The Government opposed the petition tooth and nail, even as the petitioners argued that there was no evidence connecting internet restrictions and quelling the spread of propaganda, and that there were a host of other, less-restrictive alternatives than a blanket internet ban.

On May 11, 20202, the Supreme Court, in its judgment, examined this issue with the view that the ‘fundamental rights’ of citizens need to be ‘balanced with national security’ concerns when necessary. The Court took cognizance of the fact that, the order banning 4G internet, does not provide any reasons to reflect that all the districts of the Union Territory of J&K require the imposition of such restrictions. Yet, recognizing that Kashmir has been plagued with militancy, the Court refused to set aside the orders and merely reiterated that ” the authorities are required to pass orders concerning only those areas, where there is an absolute necessity of such restrictions to be imposed…”. The Court ordered for another Special Committee to be set up to decide the matter.

The judgments in Anuradha Bhasin and Foundation for Media Professionals follow the same pattern of summarising the legal position and laying down important principles regarding access to the internet, whilst refraining from granting any relief to the people of Kashmir. Yet again the Court stops short of applying the settled law and principles to the factual matrix of Kashmir and instead constitutes a Special Committee to perform the task. There is a fundamental problem when the Court accepts security threats as qualifiers to the fundamental rights of persons in Kashmir. In doing so, the Court effectively approves the State’s version of diluted citizenship for the people of Kashmir. Holding that the arguments of the petitioners would warrant serious consideration in ‘ordinary times’ but not when the ‘outside forces are trying to infiltrate the borders and destabilize the integrity of the nation’, only further erodes the belief in the Constitutional Court as the protector against State excesses.

Supreme Court: Other matters concerning India

Over the past year, the Supreme Court has taken up and passed judgments in crucial and controversial matters, including Babri Masjid demolition case which was heard over continuous days from August 6, 2019 to October 16, 2019, in what is the second-longest argument in the history of the Supreme Court. A Constitution Bench also passed its verdict in the Sabarimala matter, referring to a larger bench, the review petitions filed against the right of women to enter the Sabarimala Temple, among other questions. The Court in other matters held that the Chief Justice of India came under the ambit of the Right to Information Act, 2005, and settled interpretation of section 24(2) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 besides cementing the equal rights of female officers in the Armed Forces of the country.

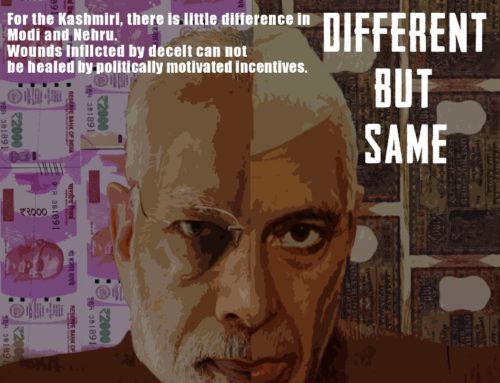

However, in matters concerning direct challenge to the policy of the Modi government, there appears to be undue delay in deciding cases and pronouncing judgements. The readers will recall the fateful ‘demonetisation’ which was unleashed on November 8, 2016 and challenged thereafter in a slew of matters before the Supreme Court, which was then referred to a Constitutional Bench on December 16, 2016. These matters are yet to be taken up. Demonetisation was not the first matter challenging the Modi government’s policy moves. Several other crucial matters such as challenges to the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 and electoral bonds issue remain pending, just like the challenges to the amendment of Article 370 and related cases. Legal scholar Gautam Bhatia argues that this is ‘judicial evasion’ where courts avoid deciding a thorny and time-sensitive question, and yet this very avoidance is, effectively, a decision in favor of the government, given that the government benefits from the status quo being maintained. Needless to add, a necessary consequence of this evasion is that the very decision becomes a fait accompli, and a decision in the future, if at all, is inconsequential. This also hits the public perception of an independent judiciary, especially when the Court fails to take up matters on which public opinion is sharply divided. There is now a noticeable trend of the Supreme Court of not taking up and deciding matters, especially those that have far-reaching impacts on the rights of people.

Conclusion

At the time of the framing of the Constitution, when Article 32 (numbered as Article 25 in the draft Constitution) was being debated,Ambedkar stated that: “If I was asked to name any particular article in this Constitution as the most important – an article without which this Constitution would be a nullity – I could not refer to any other article except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it”. The reason being, that alongside the guarantee of fundamental rights, Article 32 provided a remedy for its enforcement. The Supreme Court once observed: “The Constitutional Courts are entrusted with the critical task of expounding the provisions of the Constitution and further while carrying out this essential function, they are duty-bound to ensure and preserve the rights and liberties of the citizens without disturbing the very fundamental principles which form the foundational base of the Constitution.” The objective exercise of this power is necessary since it can have the effect of legitimizing government action as opposed to protecting the Constitution against any undue encroachment by the government. Invoking this duty, several petitions have been filed before the Supreme Court post August 5, with the expectation that the Supreme Court would inquire into the actions of the Government and when necessary, the Court would declare the same as unconstitutional and void. Unfortunately, this was not to be.

The foregoing overview of how the High Court of J&K and the Supreme Court of India have handled the pressing concerns of violations of fundamental rights and suspension of democratic principles in Kashmir since August 2019, is disappointing to say the very least. It would suffice to say that the Constitutional Courts have failed to discharge their judicial duty. Article 32 guarantees remedy at the hands of the Supreme Court in the event of a violation of fundamental rights. It has been long held that the fundamental right to move the Supreme Court under this provision constitutes the cornerstone of the democratic edifice raised by the Constitution. The Supreme Court should regard itself ‘as the protector and guarantor of fundamental rights’, and it should declare that “it cannot, consistent with the responsibility laid upon it, refuse to entertain applications seeking protection against infringements of such rights”.

There is a rather alarming outcome when the Court, after concluding that there is a violation of rights, in deference to the Government’s claims of security threats, creates an exception to the protection of fundamental rights. The message sent out is that the Government is well within its right to circumscribe the enjoyment of rights, on its sole assessment of security threats, and no judicial review of such actions by the state can be brooked. Further, it appears that the rights of the people of Kashmir are determined purely on the apprehension of the actions of certain persons in Kashmir, and Pakistan, and not based on the Constitution of India. In effect, there is judicial acceptance of the government sponsored notion that Kashmiris are not entitled to equal protection of the law even after the rhetoric of ‘one-country-one-Constitution’ accompanied the de-operationalisation of Article 370. When there are no discernible judicial standards to scrutinize claims of security threats, how is it conscionable for the same to be used to circumscribe rights? This is even more alarming considering that the very violent acts, which the internet ban purported to thwart, took place when there were restrictions on the internet! Clearly, the perceived security threat by the Government overrides any logic, let alone judicial review.

In dealing with people’s rights in conflict areas (besides Kashmir) the Supreme Court, in the past, at the very least, has recognised the need for judicial review of security threat claims and issued cautions. The Apex Court has however failed to live up to its once known liberal image – which gave paramount importance to fundamental rights of people and protection of democracy – when it comes to matters concerning Kashmir. This can be observed not just post August 5, 2019, but for the last 70 years. The experience in the Constitutional Courts, post August 5, has notably been of delay or failure to act even when violations are acknowledged and accepted. Constitutional safeguards appear to be suspended in exceptional circumstances of Kashmir. The so-called extraordinary circumstances are compelling enough, even for the Supreme Court to judicially approve the unequal protection of the rights of people of Kashmir. Effectively, the fundamental right to a judicial remedy under Article 32 is unavailable to people of Kashmir given the “compelling circumstances of cross-border terrorism”, even though there has been no proclamation of Emergency yet by the Indian Government.

Why, then, are people approaching the Constitutional Courts? What is it that they expect? Is there an inherent belief that they will be victorious in their cases? These questions are especially pertinent concerning the public interest litigations challenging the amendment of Article 370 and the bifurcation of J&K while taking away Kashmir’s special status. It can, however, be said, that this litigation has been engaged in without much participation of the people in Kashmir who resist the Central Government’s decisions and have different aspirations for Kashmir. This also assumes relevance when one seeks to assess the impact of the outcome of these litigations on the aspirations of the Kashmiri people. History has shown that legal victories do not necessarily translate into social change for the disempowered and oppressed sections of society. Rights, dependent on the goodwill of the Courts, can never be secure. An analysis of the struggles of the African-American communities in the United States reveals that the famed ‘Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka’ in 1954 did not bring about integration. Similarly, the judgment in Safai Karamchari Andolan has not abolished manual scavenging nor has the passing of Navtej Singh Johar ensured society’s acceptance and an end to discrimination of same-sex relations. Society must change for the courts to follow suit effectively. In the present times, with shrill hyper-nationalism worn like a badge of honor, barring exceptions, the dominant view in India is one of territorial integrity vis-à-vis Kashmir. The dismantling of the limited protection afforded to the state of J&K in self-governance, territorial integrity, and the collective rights to land and livelihood, was part of the ruling Party’s agenda and manifesto. What the legal challenge to the de-operationalisation of Article 370, in reality, seeks to achieve is a political agenda, which, having learned through the history of the Supreme Court, is a distinct impossibility.

Till the political resolution of the Kashmir conflict is achieved, the excesses of the Indian state would continue to be questioned before the Constitutional Courts of India. One can only hope that the distinction between the political executive and the sentinel on the qui vive is not eroded to the point of erasure.

References

- World Justice Project (2020). ‘Rule of Law Index’. Retrieved from https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/WJP-ROLI-2020-Online_0.pdf.

- The report relies on eight sectors – constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, public order and security, regulatory enforcement, and civil and criminal justice – to determine the situation of rule of law in particular countries.

- (October 2019), ‘Imprisoned Resistance – 5th August and its Aftermath’, Para 6.8. Retrieved from http://www.pucl.org/sites/default/files/reports/Imprisoned%20Resistance-final%20for%20dissemination.pdf.

- Zargar, A (27 Jun 2020) ‘99% Habeas Corpus Filed in J&K HC Since August 2019 Pending’. Newsclick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/99%25-Habeas-Corpus-Filed-Jammu-Kashmir-HC-August-2019-Pending

- The Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA), 1978

- Mian Abdul Qayoom v. State of J&K and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 07.02.2020, WP(Crl) No. 25/2019.

- Mian Abdul Qayoom v. UT of J&K and Ors, Supreme Court of India, dated 04.05.2020, LPA No.28/2020 in WP (Crl) No.251/2019.

- Foundation For Media Professionals v. UT of J&K and Anr., Supreme Court of India, reply dated 28.04.2020, WP (C) DIARY No. 10817/2020.

- Suhail Rashid Bhat v. St. of J&K and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 25.10.2019; PIL 24/2018

- In Re: Court on Its Own Motion, Supreme Court of India dated 16.04.2020.

- Azra Usmail v. UT of J&K, Supreme Court of India dated 03.04.2020; WP(C) PIL no. 4/2020 c/w WP(C) PIL no. 5/2020.

- J&K HC Bar Association v. UoI, Supreme Court of India dated 11.03.2020; WP(C) (PIL) no.14/2016.

- Dr. Shah Faesal & Ors. v. Union of India & Anr., Supreme Court of India dated 02.03.2020, WP(C) No. 1099/2019.

- Mohammad Aleem Syed v. Union of India, Supreme Court of India dated 19.11.2019, WP(Cri) No. 225/2019.

- Sitaram Yechury v. Union of India, Supreme Court of India dated 28.01.2020, WP (Cri) No. 229/2019.

- Shafin Jahan vs. Asokan K.M. and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 08.03.2018, AIR 2018 SC 1933.

- Sitaram Yechury v. Union of India & Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 28.08.2019, W.P. (Criminal)No. 229/2019.

- Justice K.S. Puttaswamy vs Union of India, Supreme Court of India dated 24.08.2017, AIR 2017 SC 4161.

- Supra note 130

- Enakshi Ganguly v. Union of India, Supreme Court of India, WP(C) No. 1166/2019.

- Chaudhary, N. (December 13, 2019). ‘SC Accepts JK Juvenile Justice Committee’s Findings Against Allegations Of Illegal Detention Of Children In Kashmir’. LiveLaw. Retrieved from: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/sc-accepts-jk-juvenile-justice-committees-findings-that-no-children-are-illegally-detained-in-kashmir-150774”

- M Siddiq through Lrs v Mahant Suresh Das and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 09.11.2019, 2020 (1) SCC 1.

- Kantaru Rajeevaru v Indian Young Lawyers Association, Supreme Court of India dated 14.11.2019, W.P.(C) No.373 of 2006.

- Central Public Information Officer, Supreme Court of India v. Subhash Chandra Agrawal, Supreme Court of India dated 13.11.2019, 2019 (16) SCALE 40.

- Indore Development Authority Vs. Manoharlal and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 06.03.2020, MANU/SC/0300/2020.

- The Secretary, Ministry of Defence Vs. Babita Puniya and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 17.02.2020, 2020 (3) SCALE 712 and Union of India and Ors. Vs. Annie Nagaraja and Ors., Supreme Court of India dated 17.03.2020, MANU/SC/0307/2020.

- Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings), Vol. VII (9.12.1948).

- The Government of NCT of Delhi v. Union of India, Supreme Court of India dated 04.07.2019, (2018) 8 SCC 501.

- Romesh Thappar vs The State Of Madras, Supreme Court of India dated 26.05.1960, AIR 1950 SC 124.

- Rashid,M. (8 July, 2016)‘Manipur Extra Judicial Killings: Allegation of excessive force by Police or Armed Forces must be thoroughly enquired into: SC’. Live Law. Retrieved from https://www.livelaw.in/manipur-extra-judicial-killings-allegation-excessive-force-police-armed-forces-must-thoroughly-enquired-sc/

About the Author: Saranga Ugalmugle is an advocate in the High Court of Bombay. She is pursuing LLM from Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (2020-2021).

Clifton D’ Rozario is an advocate and part of the All India People’s Forum, Bengaluru. Both the authors were part of an eleven-member team that visited Kashmir in September 2019.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.