State of Supreme Lawlessness

Mirza Saaib Bég

When it comes to democracy, liberty of thought and expression is a cardinal value that is of paramount significance under our constitutional scheme.

—Supreme Court of India, Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, March 24, 2015

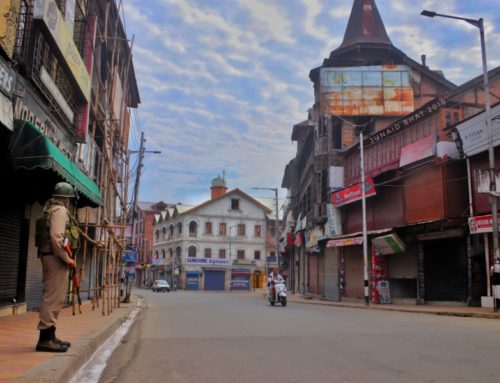

During the communication shutdown in Kashmir, many Kashmiris living outside Kashmir were unable to speak to their families for over 70 days. Some were fortunate to have parents who could walk a few miles to the nearest working phone, at the local police station, wait in lines and speak for a few seconds.

PM Modi’s Prediction

On September 16, a Supreme Court bench, headed by Chief Justice of India, heard some of the tagged matters concerning the developments in Kashmir and something peculiar occurred. One by one, senior counsels came up and reiterated different constructions of the same issue- Even after 70 days of collective punishment by way of communication ban, the people of Kashmir still had not been given any information on what authority of law had been used to impose this ban. There was no order in the public domain that informed the public why this ban had been imposed. There was no official communication by the Government on how long it was going to last. An act that inflicted such sweeping and collective punishment, against free speech, was shrouded in mystery and darkness. Ironically, in June 2014, after a month in office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi asserted “our democracy will not sustain if we can’t guarantee freedom of speech and expression.” Most listeners assumed he was cautioning them but his actions make it seem that he was actually making a prediction.

Abdication of Duty by the Court

On August 13, 2019, the 8th day of communication blockade, a three-judge Supreme Court bench, headed by Justice Arun Mishra, accepted the argument made by India’s Attorney General KK Venugopal, the Government’s highest ranked law officer, that the shutdown of communication was needed for law and order, adding further that “it will be settled soon.” The court accepted this submission and observed that “if the situation continues, the petitioner can come to court.” Even 5 months into the communication blockade, the petitioners came to court many times but there were no answers and no directions from the Court.

The intention of the Government can be gauged – If the order or the grounds of blockade are properly disclosed, affected individuals will pursue appropriate legal remedy. By deflecting all calls for such disclosure, the state was effectively delaying any opportunity of pursuing a legal remedy. It appeared to be an exercise of grotesquely undemocratic means.

If the Supreme Court of India fails to rise to the occasion and exercises its power to ensure appropriate disclosure, it would amount to a repudiation of principles that the Court is expected to stand by. In one of the hearings on the developments in Kashmir, a lawyer for the petitioners suggested that the Government wanted to suppress the Court from discharging its duties. The Chief Justice of India firmly replied, “we know our duties.”

Eventually when the Court ruled on this issue in January, 2020, five months into the blockade of communication, the Court refrained from striking down the ban and did not even comment on the legality of the blockade- which was the primary duty of the Court in this case.

Situation on ground

There were many fact-finding teams of journalists and activists that have visited Kashmir and every team has reported that the situation is nearing a catastrophe. According to the report by Network of Women in Media and Free Speech Collective, newsgathering in Kashmir has been “in peril” and newspapers/ periodicals were forced to suspend publication after August 5. The “key findings” state “it is clear that the government pulled off the total ban on communication by ordering private telecom operators and cable television service providers to suspend their services. None of this appears to be in writing.”

The report by Kavitha Krishnan, Jean Dreze and their team reiterates on similar lines, “at least 600 political leaders and civil society activists are under arrest. There is no clear information on what laws are invoked to arrest them, or where they are being held.” The report also highlights the “undeclared censorship” on media in Kashmir through a conversation with a local journalist- “Without the internet, we do not get any feed from agencies. We were reduced to reporting the J&K related developments in Parliament, from NDTV! This is undeclared censorship.” Due to the blockade of the internet, there is a shortage of medicines in the region. The report captures the situation in this paragraph – “an asthmatic auto driver in Srinagar, showed us his last remaining dose of salbutamol and asthalin. He had been trying for the past several days to buy more – but the chemists’ shops and hospitals in his area had run out of stocks. He could go to other, bigger hospitals – but CRPF would prevent him. He showed us the empty, crushed cover of one asthalin inhaler – when he told a CRPF man he needed to go further to get the medicine, the man stamped on the cover with his boot.”

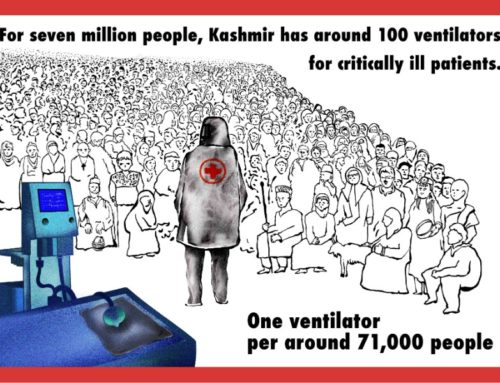

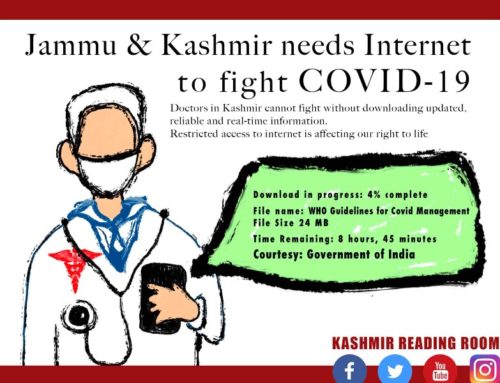

Petition filed by Dr. Sameer Kaul

A petition filed before the Supreme Court of India, by oncologist Dr. Sameer Kaul highlights the case of Bilquees Majeed Naqash w/o Rafi Kirmani R/o Ellahibagh Srinagar – who was operated for astrocytoma tumors and now requires radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment. Without internet access at the hospitals, she has not been able to get treatment from her oncologists from the last one month. Another case highlighted in this petition is that of a patient from Sopore, undergoing tests for cancer. He had undergone a biopsy test on July 27, 2019 from a collection centre in Sopore. He has been unable to receive the report due to lack of internet access in hospitals resulting in delay to a possible treatment.

The petition urges that at the very least medical and other essential centres be allowed to resume communication lines. Most hospitals host their databases on servers online. Shipping of drugs and instruments, ordering, making payments and subsequent tracking of shipment all happen online. Pharmacists relying on online delivery systems, baby food supplies and a host of other services that relied on online systems are all affected. The petition refers to machines like MRI and CT scanners that require constant updates from servers requiring Internet connections and highlights the recklessness of the on-going internet blockade – “Instead of effectively providing health and medical services and making sure that no one is allowed to cause hindrance in discharge of such services, the government is itself creating a situation, where access to health and medical care is disturbed and hindered by blocking access of hospitals and medical establishments to Information and Communication Technology. Such an action is clearly in violation of the fundamental right of health and medical care which has been recognized and included as a part of right to health as enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.”

International obligations and UN

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” The reckless actions of the Government of India are in clear violation of the UDHR. In 1979, India ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which sets forth internationally recognized standards for the protection of freedom of expression.

In the case of People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India, the Supreme Court of India has held that Article 21 of the Constitution of India in relation to human rights has to be interpreted in conformity with international law. India is also a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The rights of citizens in the online world have to be treated with yardstick as the rights in the offline world. The Internet shutdowns are a violation of the Constitutional Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression. In 2016, at the 32nd session of the United Nations General Assembly, a resolution was passed condemning these shutdowns and online access and/or dissemination of information.

During the blockade in 2019, UN representatives made statements reminding India that these communication blockades were violation of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations independent rights experts issued a statement calling for withdrawal of the restrictions. The experts highlighted again that the restrictions are “without justification from the Government”, and “are inconsistent with the fundamental norms of necessity and proportionality.” A similar statement was also issued by the United Nations experts in 2017. In 2016 the Human Rights Council, the central human rights body in the UN system, condemned such online disruptions and called upon states to avoid such shutdowns. However, none of these international condemnations seems to have made any difference.

Position of Law

It is a well-established principle of law that fundamental rights cannot be infringed upon in absence of law. The general common law rule is that delegated legislation does not come into force until it is published. There are also precedents by the Supreme Court of India that can help guide the Court on this issue – In the cases of Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting v. Cricket Association of Bengal (1995) and Sabu Mathew George v. Union of India (2017) the Supreme Court held that the citizens have the right to access, receive and disseminate information through any electronic media. The principle established in Johnson v. Sargant is that delegated legislation does not come into effect until it is published. Johnson v. Sargant was expressly followed in a British Columbia case, R. v. Ross and in India in Harla v. State of Rajasthan. In Harla v. State Of Rajasthan, Justice Bose held that natural justice requires that a law must be promulgated or published before it can become operative. The Court went on to state that “the thought that a decision reached in the secret recesses of a chamber to which the public have no access and to which even their accredited representatives have no access and of which they can normally know nothing, can nevertheless affect their lives, liberty and property …. is abhorrent to civilised man. It shocks his conscience. In the absence therefore of any law, rule, regulation or custom, we hold that a law cannot come into being in this way.”

Elected leaders, three ex-Chief Ministers, all shades of political opinion and “accredited representatives” in Kashmir have not been given any access to the laws under which the steps are being taken. There is no information/publication coming from the Government of India regarding the communication ban. A security advisory was published by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir on August 2, 2019 advising all Hindu pilgrims, in Kashmir, to immediately curtail their pilgrimage and leave Kashmir as soon as possible. After that, the only news on the development has come by way of opinion pieces and reporting in the media. On August 6,.2019, a report published in the Washington Post reported on the communication blackout that had engulfed Kashmir since the amendment of Article 370 on 5th of August. Since then, many news and media outlets have reported on the scale and effect of this blackout but there was still no official publication from the Government until 4 months into the blackout.

Shutdown of Internet

Internet shutdowns in India have been ordered under the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (CrPC) and Indian Telegraph Act 1885. Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act of 1885 allows the central or state governments to restrict or interfere with the transmission of messages, “in the interest of public safety and for maintaining public order,” though it has not been updated to specify safeguards or procedures for internet shutdowns. In 1996, the constitutionality of Section 5(2) was challenged before the Supreme Court in the case of People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India. The court held that the power can be resorted to only when “necessary.” If we are to accept the premise put forward by Attorney General KK Venugopal on August 13, 2019 that communication needed to be stopped for law and order when e-commerce, financial services, e-governance, cloud computing, media streaming also stopped. The position does not fit the criteria of “necessary” as required by the 1996 Supreme Court judgment in PUCL v. UOI. Further, we still have no order indicating that the procedure for such ban has been adhered to- In August 2017, the Department of Telecommunications of the Central Government issued new broad rules under the Telegraph Act to regulate the temporary suspension of telecom services. According to these rules, an order for suspension of telecom services can be made by a ‘competent authority’ which would be the Secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs if suspension is made by Government of India, or the Secretary to the State Government in-charge of the Home Department if the suspension is made by the State. However, ‘in unavoidable circumstances’, such an order might be issued by an officer of the rank of Joint Secretary or above who has been duly authorised by the Union Home Secretary or State Home Secretary. If the order is not confirmed by the competent authority within 24 hours it will cease to operate. The rules mandate that a copy of the order shall be forwarded to a Review Committee comprising Cabinet Secretary, and Secretaries of Legal Affairs and Department of Telecommunication or Chief Secretary, Legal Affairs and Secretary to the State Government within 24 hours. The Review Committee will have to meet within five working days of the issuance of order and record its findings on the suspension order whether it is in accordance with the provisions of sub-section (2) of section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act. In the last 45 days of communication ban, there is nothing available to the public to verify that this process has been followed.

Right to Information Act

India’s Right to Information Act is a useful tool to seek information that may be passively recorded but during an on-going situation of suspension of fundamental rights, it is misplaced to expect someone to wait patiently for 30 days to hear a response. As such, the RTI Act can not be the remedy/choice for emergency situations. If the entire state is under lockdown with even government offices and post-offices are shut, where can a Kashmiri file such an RTI? With the internet shut and travel restrictions imposed within Kashmir, how can one even make such an application? The affected persons have a right to know the instructions issued by the Home ministry and it is the responsibility of the Government to ensure that adequate steps have been taken to inform people of such instructions. However, in 2016, a Right to Information application revealed that no state authority knew who imposed the ban. Similarly, an RTI application seeking information about the 3 month long Darjeeling internet shutdown was declined, because the order authorising such indefinite shutdown was deemed “exempted from disclosure.” In such a situation, the Supreme Court must not refrain from passing directions that the order be made public instead of implying that in the interest of national security, collective punishment without disclosure of law and authority of such punishment can be an acceptable position.

Economics of Shutdowns

J&K has seen more than 180 internet shutdowns in the past few years. In 2018 alone, internet services in the Kashmir were cut off 65 times; In 2019, 55 such shutdowns have taken place this year thus far. According to a report by Delhi-based Software Freedom Law Centre, India routinely employs internet shutdowns. It is now the country with the highest number of shutdowns in the world. In 2016 the longest duration of internet shutdown in India was observed in Kashmir in 2016 due to the agitation caused by the killing of Burhan Wani on 8th July 2016. Mobile Internet Services were suspended for 133 days. While mobile Internet services on postpaid numbers were restored on November 19, 2016. Mobile Internet services for prepaid users were resumed in January 2017 implying that they faced almost a six-month Internet shutdown. In Kashmir, sometimes, the internet is allowed to remain ‘connected’ but the speed is reduced so much that uploading photos or videos would be hampered. In 2017, while most parts of Kashmir had the internet suspended, some areas were reduced to 128 Kbps. Further, there are also undefined limitations placed on content and Kashmiri social media users are routinely find their accounts suspended or deleted for social and political activism. Apart from being subject to surveillance and privacy violation, the problems for Kashmiri activists do not end with punishment in the virtual world. Many have faced legal prosecution, harassment and even physical attacks.

Day-to-day transactions, communication, online business, financial transactions and flow of information has been brought to an abrupt halt with no warning. The economic loss of such shutdowns needs to be factored in the making of such decisions. In its country report on India, Freedom House said that while the Indian government has been restricting access to the internet since 2010, especially during so-called periods of unrest. A 2016 study by Brookings Institution that looked at 81 instances of internet shutdowns across 19 countries between July 2015 and June 2016 found that they had cost the world economy a total of USD 2.4 billion. India alone, at a conservative estimate, lost nearly USD 1 Billion during this period. In contrast, similar but far less frequent bans cost USD 69 million in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and USD 48 million in war-torn Syria. The Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations Jammu & Kashmir estimated that Jammu & Kashmir lost over USD 600 million due to these shutdowns. A Deloitte study estimates the number of IoT (internet of things) units is increasing faster than ever. With this increase in IoT, the cost of an internet shutdown will increase as well. Deloitte studies data from 96 countries and estimated that

- For a country that has high internet connectivity: Per day impact of USD 23.6 million per 10 million population

- For medium-connectivity country: Per day impact of USD 6.6 million per 10 million population

- For Low-connectivity country: Per day impact of USD $0.6 million per 10 million population

The report by Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, a New Delhi-based think tank, states that 16,315 hours of internet shutdown in India from 2012 to 2017 cost the economy more than USD 3 billion. Apart from the economic impact, the cost of these intermittent shutdowns on mental health is also immense. People subject to these communication blockades are cut off from their families making them feel isolated.

Conclusion

The structure of the internet is too vast to be defined merely as a tool for communication. It affects every possible activity, many of which are not “communicative” in the human sense of communication. Governments in the past have blocked the use of specific social media apps like Facebook and WhatsApp so there are alternatives available to a blanket ban on the internet. In this light, these indefinite bans must be viewed as arbitrary, sweeping and an unconstitutional violation of the fundamental rights of people affected. The final arbiter of the issues in India is the Supreme Court of India and it is relevant to remind the Court that “national interest”, as defined by a government in power, is not a ground that qualifies the test of reasonable restriction on fundamental rights and basic human rights.

References

- Press Trust of India, (30 June 2020) ‘Supreme Court to hear pleas against Article 370’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/supreme-court-to-hear-pleas-against-article-370-move-kashmir-curbs-today/story-PXBZr1R6cpQVD0pkvk6cfJ.html

- India Today,(16 September 2020) “Kashmir media restrictions, political detentions”. India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/supreme-court-to-hear-fresh-batch-of-pleas-questioning-abrogation-of-article-370-today-1599496-2019-09-16

- Human Rights Watch, “Stifling Dissent” (24 March 2016) https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/05/24/stifling-dissent/criminalization-peaceful-expression-india

- Vaidyanathan, A & Sanyal, A (13 August 2019) ‘J&K situation very sensitive, Government should get time’ NDTV, Retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/jammu-and-kashmir-situation-very-sensitive-reasonable-time-should-be-given-to-government-to-ensure-n-2084456

- Withnall,A. (28 August 2019 ) ‘Kashmir: India’s top court is asked to reverse decision on revoking special status’ Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/india-kashmir-article-370-supreme-court-challenge-modi-pakistan-a9082221.html

- Free speech collective, ‘News Behind the Barbed Wire’ (4 September 2019) https://freespeechcollective.in/2019/09/04/news-behind-the-barbed-wire-kashmirs-information-blockade/

- Kashmir Caged: A Fact-Finding Report by Jean Drèze, Kavita Krishnan, Maimoona Mollah and Vimal Bhai 14 August 2019 https://www.nchro.org/index.php/2019/08/14/kashmir-caged-a-fact-finding-report-by-jean-dreze-kavita-krishnan-maimoona-mollah-and-vimal-bhai/

- NWMI reports ‘News Behind the Barbed Wire’, Free Speech Collective. Retrieved from https://freespeechcollectivedotin.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/news-behind-the-barbed-wire-nwmi-fsc-report-2.pdf

- Network of women in media, India. Retrieved from http://nwmindia.org/

- Free speech collective. Retrieved from https://freespeechcollective.in/

- Peoples Dispatch, “Kashmir Caged Report”. Retrieved from https://peoplesdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Kashmir-Caged-final-report.pdf

- Chaudhary, N (12 September 2019) “National Conference Leader Moves SC For Restoration Of Internet And Landline Services In J&K Hospitals” Live Law. Retrieved from https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/national-conference-leader-sc-restoration-of-internet-and-landline-services-in-jk-hospitals-147989

- Goyal, V. Singh, K. & Yasir,S (14 August 2019) ‘India Shut Down Kashmir’s Internet Access’, New York Times, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/14/technology/india-kashmir-internet.html

- Yadavar, S and Parvaiz,A (6 September 2019)‘Healthcare Crisis in J & K’, The Wire, Retrieved from https://thewire.in/health/ground-report-healthcare-crisis-in-j-ayushman-bharat-suspended- At the Shafie Diagnostic Centre, a public-private partnership at the Bone and Joint Hospital, the MRI machine–one of three in government hospitals here–suffers glitches, but it is not getting its software updates and company technicians have not been able to find out what is wrong.

- Plea in SC seeks restoration of Internet, phones at hospitals across Jammu and Kashmir, The Hindu, 12 September 2019 https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/plea-in-sc-seeks-restoration-of-internet-phones-at-hospitals/article29402548.ece

- UN Treaty Body Database https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=79&Lang=EN

- (1997) 1 SCC 301

- United Nations, General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil,political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development., Thirty-second session, Agenda item 3, 27th June 2016.

- UN rights experts urge India to end communications shutdown in Kashmir, United Nations Human rights office of high commissioner, UN, “Kashmir communications shutdown a ‘collective punishment’ that must be reversed” https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044741

- https://ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24909&LangID=E

- UN HRC, (11 May 2017) ‘India must restore internet and social media networks in Jammu and Kashmir’, Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21604&LangID=E

- Kharak Singh v. State of UP https://indiankanoon.org/doc/619152/ ; Also see Gautam Bhatia “The 16th September Order and the Supreme Court of Convenience” Indian Constitutional Law https://indconlawphil.wordpress.com/2019/09/18/the-16th-september-order-and-the-supreme-court-of-convenience-or-why-separation-of-powers-is-like-love/?fbclid=IwAR3jSTaxYLHmbuX9eWQkB474P_tSL9Z5-frN6qVPniW_aqtS44EO_P98lA4

- Bhattacharya, P. “Human Rights and Internet Shut-Downs in Jammu & Kashmir” Oxford Human Rights Hub. Retrieved from https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/human-rights-and-internet-shut-downs-in-jammu-kashmir/

- [1918] 1 K.B. 101

- [1945] 1 W.W.R. 590, noted (1946) 24 C.B.R. 149. Also see Minister of Mines v. Harney [1901] A.C. 347 (P.C.) (minister’s decision to forfeit a lease not effective until notified to lessee). Prerogative legislation by proclamation could not generally come into effect until published.

- 1951 AIR 467, 1952 SCR 110

- Municipal Board, Sitapur v. Prayag Narain Saigal & firm 1970 AIR 58; Raza Buland Sugar Co. Ltd v. Municipal Board, Rampur 1965 AIR 895.

- Software Freedom Law Center, (10 August 2018) ‘Parliament’s Last Opportunity to Modify Telecom Suspension Rules?’ The Quint. Retrieved from https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/parliament-telecom-suspension-rules

- Human rights watch India ‘20 Internet Shutdowns in 2017’. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/15/india-20-internet-shutdowns-2017

- Schmall, E. (29 August 2019) ‘India seeks to portray a sense of calm in locked-down Kashmir,’ Ap News . Retrieved from https://www.apnews.com/45cf214d417745b1b1ea24941b8655ba

- Nayak, N.(6 October 2017) ‘The Recently Notified Rules on the Suspension of Telecom Services’, Caravan Magazine. Retrieved from https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/suspension-telecom-services-rules-legitimise-internet-shutdowns-facilitate-voice-call-bans

- Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017, August 7, 2017, http://www.dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Suspension%20Rules.pdf?download=1.

- Pahwa, N. (28 August 2018), ‘Government of India issues rules for Internet Shutdowns’ Medianama. Retrieved from https://www.medianama.com/2017/08/223-internet-shutdowns-india

- Software Freedom Law Centre, ‘Temporary Suspension of Telecom Rules’, Retrieved from https://sflc.in/new-rules-temporary-suspension-telecom-services-case-public-emergency-or-public-safety

- Saha, A.(3 June 2017) ‘Kashmir internet ban: No one knows who ordered the shutdown,’ Hindustan times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/kashmir-internet-ban-no-one-knows-who-ordered-the-shutdown-shows-rti/story-db6f78xiCysL3iTDIY8x8H.html

- Software Freedom Law Centre, ‘Darjeeling Internet Ban’. Retrieved from https://sflc.in/rti-darjeeling-internet-ban-3-months-and-counting

- Mahajan,S.(12 September 2019) ‘How the communications shutdown is hampering medical and health services in Jammu & Kashmir’. Bar and Bench. Retrieved from https://barandbench.com/how-the-communications-shutdown-is-hampering-medical-and-health-services-in-jammu-kashmir-pil-in-sc-reveals/

- Barik, S. (30 July 2019)‘India saw 6 internet shutdowns in July, 65 so far in 2019’, Medianama . Retrieved from https://www.medianama.com/2019/07/223-india-saw-6-internet-shutdowns-in-july-65-so-far-in-2019/

- Software Freedom Law Centre, “Living In Digital Darkness Internet Shutdowns Handbook” https://sflc.in/sites/default/files/reports/Living%20in%20Digital%20Darkness%20-%20A%20Handbook%20on%20Internet%20Shutdowns%20in%20India%2c%20May%202018%20-%20by%20SFLCin.pdf

- Bahree, M.(12 November 2018) ‘India Leads The World In The Number Of Internet Shutdowns’ Forbes, . Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/meghabahree/2018/11/12/india-leads-the-world-in-the-number-of-internet-shutdowns-report/

- (29 January 2018) ‘Shopian killings: Valley shuts in mourning’, Kashmir Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.kashmirmonitor.in/Details/142069/shopian-killings-valley-shuts-in-mourning

- West, D. ‘Internet shutdowns cost countries $2.4 billion last year’ Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/intenet-shutdowns-v-3.pdf

- Rajat Kathuria, Mansi Kedia, Gangesh Varma, Kaushambi Bagchi, Richa Sekhani, ‘Measuring the Economic Impact of Internet Shutdowns in India’ Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations http://icrier.org/pdf/Anatomy_of_an_Internet_Blackout.pdf

- Rithu Thomas, Preetha Devan, Abrar Khan, “The Internet of Things,” Deloitte Insights https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4420_IoT-primer/DI_IoT-Primer.pdf

- Rajat Kathuria, Mansi Kedia, Gangesh Varma, Kaushambi Bagchi, Richa Sekhani, “Measuring the Economic Impact of Internet Shutdowns in India” Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations http://icrier.org/pdf/Anatomy_of_an_Internet_Blackout.pdf

About the Author: Mirza Saaib Bég is a Kashmiri lawyer and an alumnus of NALSAR University of Law. He is currently in the UK to pursue a Master’s in Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford as a Weidenfeld- Hoffman scholar.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.