Ladakh – Experience as a Union Territory

Mustafa Haji

Ladakh Was a Separate Kingdom till 1834

In 1834 the Dogra Maharaja Gulab Singh conquered the independent Kingdom of Ladakh through one of his generals, Zorawar Singh and remained under the Dogras till the fall of the British rule. In its heyday the territory of Ladakh extended from Jammu to Lhasa and Gilgit Baltistan. Skardo (Gilgit-Baltistan) which is currently under Pakistan-Administration used to be the Winter Capital and Leh the summer capital. Owing to the central equidistant location between Skardo and Srinagar, Kargil became a centre of trade between Skardo, Srinagar, Leh and Zanska. Over the years, Kargil became a resting place for the traders and travellers to and from Central Asia and South-East Asia, and Yarkand (China).

Unbeknownst to the people of Kargil, this seemingly advantageous location would one day be reduced to a precarious position.

Leh and Kargil

After Partition in the subcontinent, Ladakh was stitched up as one district within Jammu & Kashmir (J&K). It comprises Kargil and Leh. In 1979 Kargil would be carved into a separate district, but only to be side-lined by Leh in most aspects. The last 40 years have witnessed very different growth trajectories of the socio-political states in Leh and Kargil. Leh progressed rapidly as the political and tourism hub- so much so that in many imaginations Leh became synonymous to Ladakh whereas Kargil was reduced to being just a stop on the way. Leh’s monasteries, stupas, landscapes and the serene lakes fit in the exact imagination of a person who fantasizes Ladakh to be a “land of lamas and wanderlust”. This image of Ladakh runs in the advertisements, news and all kinds of discourse popularised in India.

Kargil is a Muslim majority region with Buddhists as the second majority. Over the years it has rather come to be known by the Kargil war. It is worth mentioning that Bollywood war movies only further solidified the war-zone image. Not many people realize that Kargil is one of the two districts in Ladakh, in fact the only other district after Leh and that too with a bigger population.

Having all the discourse set around Leh has inevitably steered most of the attention away from Kargil, both from the central as well as the state government. This reflects in the number of government institutions with head offices located in Leh, the level of development in the Leh town, the number of NGOs and the tremendous support they get, the voices that reverberate in the policy corridors; all in the name of Ladakh, whereas very little of it can be seen in Kargil.

The prejudice can be seen in the writers who have been writing on Ladakh also as most the writings on Ladakh have been centred around Leh with little to no focus on Kargil. Whatever available literature is found on Kargil, it depicts a grim, bleak picture. John Da Silva in his recent account on Ladakh writes-

“After Kargil the road bends south and as the sun has not yet risen over the mountains, we travelled the next twenty-five miles in Shadow. The dwellings by the roadside had an untidy and furtive appearance and the few women we saw turned away, covering their faces. Our last glimpse was a tiny mosque with a Golden dome in the darkened fields before we emerged into sunlight at Mulbekh and saw a Buddhist Monastery high on the hill to our left… It seemed that we emerged metaphorically as well as actually out of darkness into light”

Kargil has been protesting for the Zojila tunnel (which will connect Ladakh to Kashmir) for the last 70 years, but this demand has been kept in abeyance for the longest time. Recently a divisional status was granted for Ladakh making it the third division after Jammu and Srinagar, but all the headquarters were to be stationed at Leh. It took 10 days of civilian protests for the government to agree on making the status sharing between the two districts, only for the arrangement to become redundant due to the new bifurcation.

Theocratic influence

The political milieu in Kargil is more of a theocratic nature; the two Shia Schools, Islamia School and the Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust (IKMT) have a huge influence on the daily discourse in Kargil. Apart from their influence over the socio-politics, their influence is deeply rooted in every aspect of Kargil and surprisingly, the two organizations do not get along well. A recent example of the vendetta between the two is losing the Member of Parliament seat to Leh even after having a bigger voter turnout. It was solely because both the institutions had proposed a candidate of their own. This was the scenario in the previous parliamentary election as well. The issue of corruption, nepotism and religious orthodoxy is more visible in Kargil than in Leh. The last major recruitment drive for General Line teachers and Village Level workers resulted in protests the selection as masses had accused the authorities of nepotism and corruption.

Kargil’s Dependence on Kashmir and Jammu

Although culturally and ethnically Ladakh is common from Matayen in Drass to Nubra valley in Leh, the difference in the aspirations of Leh and Kargil has a lot to do with the problems of accessibility. With a surface area of 59,146 km² and a population of just 274,289 many places in Ladakh are sparsely populated. Kargil is closer to Srinagar than it is to Leh. Drass, one of the biggest blocks of Kargil district is just 150 km from Srinagar and has very harsh winters even by the standards of Ladakh – the mercury dips below minus 30 degrees which forces people to migrate to places in the Kashmir or Jammu region before winter sets in. Decades of difficulties owing to lack of amenities and opportunities led to many people from Kargil settling in Jammu or Kashmir.

Unlike Leh, which has a commercial Airport that operates throughout the year and an alternate land route via Manali in summers, Kargil is left with no alternative to depend on Kashmir. Residents are left dependent on the erratically available Army Air Courier service which occasionally ferries the locals in Kargil in winters. Ladakh gets cut off from the world in winters for almost 6 months with having no point of access other than going to Leh and then taking a flight whenever someone wants to go out of Ladakh. To access the High Court in Srinagar- a person from Kargil must take a detour from Leh and spend thousands of rupees which only a few can afford, instead of directly traveling to Srinagar which is closer to Kargil.

The status of Ladakh Post August 5, 2019

It is now gradually dawning on many that the reconstitution of Ladakh as a UT under the Jammu and Kashmir reorganization Act, 2019, following the revocation of Jammu & Kashmir’s (J&K) special status, has not solved Ladakh’s problems once and for all; it has created a new set of dilemmas for the locals. There is a gap between the dream of a union territory called Ladakh, with extended autonomy, and the UT that seems to be firmly under the thumb of the LG office and its bureaucracy.

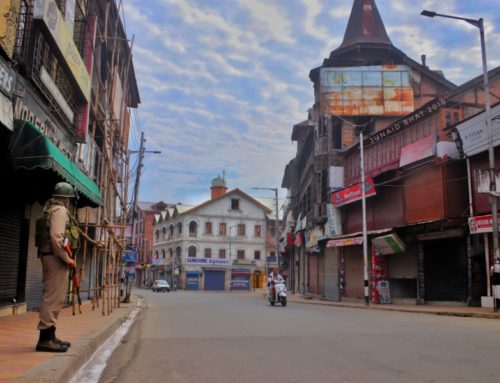

Viral images and situation on ground in Kargil

The immediate response to Ladakh’s reconstitution as a union territory last year was mixed. Leh district saw an outpouring of celebration on the street and in the main market. The pictures of Ladakh’s sole Member of Parliament, Jamyang Tsering Namgyal, dancing went viral just like the Bharatiya Janata Party MP’s speech in Parliament had been during the debate on the J&K Reorganisation Bill. However, it is important to highlight that the same excitement was not visible in Kargil due to several reasons: The Union Territory has its headquarters in Leh, therefore the people of Kargil must travel a greater distance for official work than they did earlier. Further, the new UT does not have any provisions for the protection of land rights and job reservations either. And again, Kargil’s demand for the Zojila tunnel, to provide year – round connectivity, has been stalled for several years.

Ladakh never asked for UT without legislature

The demand for UT status for Ladakh had been a longstanding one for various reasons. When it was finally accepted, the timing of it surprised many because there was no urgent circumstance necessitating it. Moreover, the reality of Ladakh as a union territory does not coincide with the conception of the kind of UT the people of Ladakh had envisaged. The people had assumed that if Ladakh was to get UT status, it would come with a legislature; there were four MLAs and two legislative council members who used to represent it in the legislature of the erstwhile state of J&K. An UT devoid of a legislature meant an LG-centric administration. This was perhaps the just the first disappointment for the Ladakhis.

No Roadmap/vision for Union Territory

While the rest of J&K remained under an unprecedented lockdown, including a blockade of internet service, Kargil was placed under curfew, and those in Leh put up a celebratory front. Once the celebrations in Leh dimmed down, discussions began on how the UT would function. There were many discussions on this aspect, which were attended by people from all walks of life, including leaders, students, lawyers, academics and ordinary people. The Hill Council of Leh even sent a team of members and officials to study the administrative working of an UT. The sudden surge of haphazard activities proved that there had been no prior research or study undertaken to plan the kind of union territory that would be appropriate for Ladakh and specific to its concerns. Even the Ladakh Buddhist Association, which was by far the biggest advocate of UT status for Ladakh did not seem to have a roadmap.

There was a fresh anxiety too, there would now be an influx of outsiders buying up land or commencing industrial enterprises which would dilute the distinct culture and affect the fragile ecology of the land. Rumours of people showing interest in buying land in Ladakh had already surfaced leading to protests by locals.

Demand for 6th Schedule Status

A fresh round of debates began, this time about the need to be given a 6th Schedule status. (The Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution comprises provisions for the administration of tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram, providing safeguards for tribal dominated areas). The public opinion was that only a 6th Schedule status would enable Ladakh to preserve its cultural identity and environment and secure jobs for its people.

The Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh (HIAL), headed by prominent Ladakhi figure and Ramon Magsasay awardee, Sonam Wangchuk, organised study tours to Sixth Schedule states to get an idea of the system that had been put in place to protect their distinct cultures, land and ecology. In addition to the study tours, there were protests spearheaded by students in Leh who went on hunger strike in the cold winter, in mid-November.

In the meantime, Ladakh formally became a Union territory on October 31, 2019, and the office of the Lieutenant Governor (LG), along with several senior bureaucrats, assumed charge. There are several changes – from just two District Commissioners, the strength of Ladakh’s senior bureaucracy has grown to five with the addition of three senior IAS officers – Advisor to the Governor, Commissioner Secretary, and Divisional Commissioner- assisting the LG office. There is also the office of the Inspector General of Police, followed by various Directors who are mostly from the state civil service. This new administrative set-up was in the process of settling down and acclimatizing to the difficult climatic conditions and terrain of Ladakh when the Coronavirus crisis was unleashed. The new executive swung into action and took control of the situation, gathering plaudits in the process.

COVID-19 fault-lines and Collision in Ladakh

As different parts of India have grappled with a rapid rise in COVID 19 cases in the last four weeks or so, the manner in which the five month old Union Territory of Ladakh and its new, Lt. Governor – headed administrative set-up has tackled the crisis has been appreciated. The irony is that the efforts of the LG office to protect the people of Ladakh from the infectious disease have put it on a collision course with the elected members of the very institutions based on the principle of people’s participation in the planning process — democratic decentralization – namely, the autonomous hill development councils of Leh and Kargil; bodies that came into being after much struggle by the people of Ladakh.

Actions such as ordering a shutdown of the Leh Council’s office for a few days or reopening the Zojila pass and taking over the distribution of essential commodities, the remit of the Kargil Council, to name a few, have created such an opaque atmosphere. Tensions reached such a high that members of the latter held a press conference some days ago complaining about a non-responsive LG office and threatened mass resignation. These events have exposed the fault-lines running through the core of the unplanned decision to make Ladakh a Union Territory. Fault-lines that foreground the absence of a well-thought out roadmap despite a longstanding demand and agitation for the status of UT for Ladakh.

The war on the new Coronavirus was being won in Ladakh but the zeal of the bureaucrats had started to unnerve the Autonomous Hill Development Councils (Hill Council) in Leh and Kargil. In a straight clash of power in Kargil, the District Magistrate wrote against the Executive Counsellor (EC) Health for breaking the curfew and visiting a village. The EC argued that being the head of the health department in the Hill Council he was duty bound to attend to distress calls. As mentioned earlier, the Hill Council office in Leh was ordered to close down for some days and the Kargil Hill Council found itself being side-lined as the LG office took over the task of reopening the Zojila pass and distribution of essentials to locals. At a press conference held a few weeks ago, members of the Kargil Hill Council said they would resign en masse if their demand of evacuation of Ladakhi pilgrims and students stuck in foreign countries was not heeded. Many political leaders from Leh, even the ones from the BJP, have shown their discontent with the LG office on several other occasions.

It is worth noting that the Hill Councils in Leh and Kargil are the outcome of the struggle of the Ladakhi people, especially the people of Leh, against marginalisation. The Hill Council of Leh was created with the holding of elections in 1995, and the Kargil Hill Council came into being in 2003. They are also part of the bigger project of decentralization in India, with people’s participation in the planning process shaping development according to grassroot realities and needs. The Hill Councils of Leh and Kargil have existed for close to two decades now and the BJP government had even extended many of its powers in 2018 for the same reasons. With an unprecedentedly large and controlling bureaucracy taking over in Ladakh, it remains to be seen how the elected representatives will survive.

“1st Independence Day”?

On Independence Day last year, a huge banner was hung in the main market of Leh which read “Union Territory of Ladakh celebrates its 1st Independence Day”. Mr. Sonam Wangchuk congratulated everyone with the same euphoric note. For Ladakhis the word ‘independence’ clearly meant freedom, or unshackling themselves from the rule of Kashmiri leaders who due to their Kashmir-centric agenda sorely neglected regions like Ladakh.

However, months after Ladakh formally became a Union Territory, reality has asserted itself. The lack of any clear roadmap in the minds of the Ladakhis, the inconclusive debates over the proposed 6th schedule status for Ladakh, and the Hill Councils’ struggle to co-exist with the LG office and assert their powers, makes one wonder if the word ‘independence’ on the banner held another meaning for the Ladakhis – namely, unshackling themselves from their autonomy as well?

The creation of two union territories upends the decades of links and ties that have been built between Kashmir and Kargil. There is a shared grievance of the people of Leh and Kargil that they did not get their due in Kashmir. This is a grievance that needs to be addressed politically and democratically. But a Union Territory for Ladakh that is devoid of a legislature, land protection laws and job security, is something we never asked for and it is not acceptable to the people of Kargil.

References

- Wedge, J. F. N and Hamilton, C (1987). ‘The society’s tour to Kashmir and Ladakh’. Asian Affairs. 18:1, 45-44.

- Alexandra Ulmer, “India’s Ladakh Buddhist enclave jubilant at new status but China angered”, Reuters, August 6, 2019 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-ladakh/indias-ladakh-buddhist-enclave-jubilant-at-new-status-but-china-angered-idUSKCN1UW1QL

- News 18 (26 December 2019). ‘Mercury Falls to Minus 30.2 Degree Celsius in Drass Belt of Kargil’. News18. Retrieved from https://www.news18.com/news/india/mercury-falls-to-minus-30-2-degree-celsius-in-drass-belt-of-kargil-2436791.html#:~:text=Share%20this%3A,Celsius%2C%20Meteorological%20Department%20official%20said.

- Press Trust of India (9 September 2019). ‘Hill Council of Ladakh members call on Pondy LG’. Business Standard. Retrieved from https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/hill-council-of-ladakh-members-call-on-pondy-lg-119090900728_1.html

- ANI (6 August 2019). ‘Maharashtra govt plans MTDC resorts in Ladakh, Kashmir’. Business Standard. Retrieved from https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/maharashtra-govt-plans-mtdc-resorts-in-ladakh-kashmir-119080601751_1.html

- Rashid, H. I (11 March 2020). ‘After the UT tag, Ladakh residents seek constitutional safeguards’. Economic Times. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/after-the-ut-tag-ladakh-residents-seek-constitutional-safeguards/articleshow/74568531.cms?from=mdr

- PTI “Students stage protest demanding inclusion of Ladakh in Sixth Schedule of Constitution” Outlook, 11 December, 2019 https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/students-stage-protest-demanding-inclusion-of-ladakh-in-sixth-schedule-of-constitution/1683234

- Dharma, N (20 March 2020). ‘DC Kargil, Executive Councillor Health slug it out on corona’. Kashmir Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.thekashmirmonitor.net/dc-kargil-executive-councillor-health-slug-it-out-on-corona/

- Aswani, T (14 April 2020). ‘Ladakh Autonomous Hill Council May ‘Mass Resign Due to Lack of Essentials. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/government/ladakh-autonomous-hill-council-may-mass-resign-due-to-lack-of-essentials

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/topic/Ladakh-Autonomous-Hill-Development-Council-Act

- PTI (15 August 2019). ‘Ladakh celebrates ‘1st Independence Day’ after being declared UT’. Live Mint. Retrieved from https://www.livemint.com/news/india/ladakh-celebrates-1st-independence-day-after-being-declared-ut-1565875091148.html

About the Author: Mustafa Haji is a Lawyer, from Kargil. He was a law officer in Hyderabad and then a researcher with the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Delhi. He has written for various national and local groups. This article is an update on his previous work as published in the Wire and Caravan.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.