Bureaucratic Strangleholds over Media Freedom

Geeta Seshu

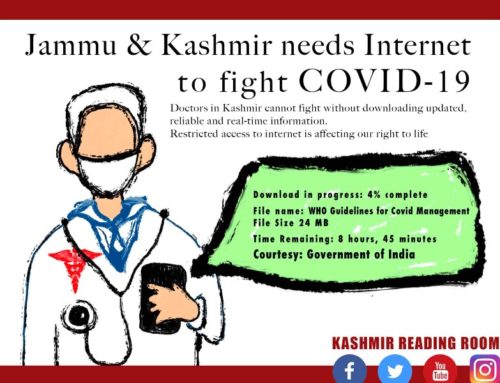

What explains the singular obduracy of the Indian state in its refusal to restore full internet connectivity to the valley, despite numerous reports of the havoc caused by it? The harsh effects were evident in statements and pleas by journalists, students and even doctors who have struggled to combat the COVID-19 pandemic without timely access to information, treatment or even the latest notifications from health agencies.

The unprecedented and total shutdown of communication in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) since August 4, 2019, a day before the amendment of Article 370, left people completely bereft in a way they had never experienced before, despite living through 70 years of turmoil and violence. The total inability to pick up the phone and talk to family, friends, colleagues and even neighbours, nearly resulting in total isolation and alienation, leaving them devoid, not just of information but of support systems and emotional succour.

The situation may have eased somewhat with 2G internet allowed in the valley from mid-January 2020, but this has made little or no difference to the plight of people, with the worst affected being health care workers and students grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic. A year on, the harassment, intimidation and false cases against journalists and slow and steady erosion of independent media has only got worse, aided by a repressive media policy that serves as additional warning to the media to behave or else…

A two-member team, of which this writer was a part, investigated the impact of the ban on communication on the media in Kashmir. Coming as it did as part of a larger shutdown, it was put into effect by the imposition of Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and the large-scale detention and arrests of leaders of mainstream political parties, separatist leaders, lawyers and youth.

There was a total communication ban, unlike in the past when Internet shutdowns were imposed on the people of Kashmir (180 since 2012 and 54 times before the current ban in 2019 alone). It resulted in the shutdown of mobiles, landlines, broadband and cable television. It also resulted in the easier dissemination of a one-dimensional state-controlled narrative in an information vacuum.

Two court cases challenged the communication blockade and an examination of the resultant judicial orders suggests that the court granted limited reprieve from the exercise of excessive administrative powers. Paradoxically, the orders denied the litigants any relief.

The effects of this shutdown and the manner in which journalists grappled with new challenges to disseminate information have been dealt with elsewhere in this report. But the two major administrative measures to curb freedom of expression – the communication blockade from August 4, 2019, and the media policy announced on June 11, 2020 reveal so much of the punishing regulatory approach of the government.

The Media policy

Nothing demonstrates this more than the ‘revised media policy’ made public more than a month after being formulated. Ostensibly to “carry the message of welfare, development and progress to the people in an effective manner”, it spells out in detail the advertising revenue policy for media houses, which would be strictly regulated for empaneled media that does not carry “anti-social and anti-national” news.

The Department of Information & Public Relations (DIPR) issued the media policy in a government order on May 15, 2020. It is a 53-page document which lays down guidelines for owners of media houses as well as the journalists they employ. The objective of the new media policy is to create “a sustained narrative on the functioning of the Government in media”.

It has exhaustive guidelines for print and electronic media and also makes it clear that government communication will move away from print towards new media. Thus, non-print media makes it to the list of ‘empaneled’ media (audio-visual and electronic media like FM, radio, satellite and cable TV channels).

But it is the guidelines for print media that need greater examination as it clearly reveals the thrust of the government’s media policy: to intimidate and warn independent media houses that they will be under scrutiny.

There are more than a thousand registered newspapers and periodicals in Kashmir. Over the last decades, print media had grown in Kashmir and was a vibrant and independent medium, drawing several talented journalists who reported on the ongoing conflict and highlighted numerous stories of the plight of the people.

Advertisements have been a major source of revenue but also of control. Since 2010, the newspaper Kashmir Times has struggled to get government advertisements. Other newspapers like Rising Kashmir and Kashmir Reader also suffered, the latter even facing a ban for a few months in 2018. No reason is ascribed for the suspension of government advertising, save reports that the newspapers were ‘anti-national’!

The policy document says that the DIPR will go into the “antecedents of the paper/news portal as well that of its publishers/editors/key personnel” before empanelment. Similarly, it will do a “robust background check including verification of antecedents of each journalist.”

According to the empanelment guidelines, which lays down the criteria for media’s eligibility to obtain government advertisements, “DIPR shall examine the content of the print, electronic and other media for fake news, plagiarism and unethical or anti-national activities. Any individual or group indulging in fake news, unethical or anti national activities or in plagiarism shall be de-empaneled besides being proceeded against under law. There shall be no release of advertisements to any media which incite or tend to incite violence, question sovereignty and integrity of India or violate the accepted norms of public decency and behavior.”

The media policy seeks to justify these measures by stating that “J&K has significant law and order and security considerations. It has been fighting a proxy war supported and abetted from across the border. In such a situation, it is extremely important that the efforts of anti-social and anti-national elements to disturb the peace are thwarted.”

For a media already struggling with slow speed internet, severely strapped by an economic shutdown and depleted revenue, the control over government advertising and the largesse that is promised to pliant media houses, spells the death knell for any kind of independent news that is even slightly critical of the powers that be.

The Bhasin petition: The Internet shutdown devil

The Executive Editor of Kashmir Times, Anuradha Bhasin, filed a petition in India’s Supreme Court arguing against the internet ban. The petition said that the ban resulted in an information blackout. It became impossible for her newspaper to get in touch with district correspondents and obtain any authentic news. The ban forced the suspension of publication of the newspaper’s edition from Srinagar since August 6, 2019.

The information blackout was a ‘direct and grave violation of the right of the people to know about the decisions that directly impact their lives and their future’ and prevented the media from reporting developments and knowing the opinions of the citizens of the state.

There was no mandatory official notification for the imposition of the internet ban, the petitioner pointed out during the hearings. However, no stay order was given on the ban and the final order, delivered on January 10, after being reserved for almost two months, held that an indefinite suspension of internet services was illegal.

A two-judge bench of Justices N.V. Ramana and V. Ramasubramanian said that orders for an internet shutdown must satisfy the tests of necessity and proportionality. However, the Court did not lift the ban on the internet, instead it directed the government to issue formal notification and review the shutdown every seven days!

The Court did make critical noises about the fact that the state failed to produce orders or notifications by which communication has been blocked in the State of J&K. It added that as a general principle, the State must proactively produce orders if there is a challenge made regarding the curtailment of fundamental rights and ensure that all the relevant orders are placed before the Court.

While the Court stopped short of getting into whether the right to access the internet is a fundamental right (despite an excellent judgement of the Kerala High Court before it), it did state that the right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a), and the right to carry on any trade or business under Article 19(1)(g), using the medium of internet, is constitutionally protected.

The Court examined the Suspension Rules under Section 7 of the Telegraph Act, under which different states were restricting telecom services including access to the internet and a Review Committee to examine these directives within five days. The court said:

“Keeping in mind the requirements of proportionality expounded in the earlier section of the judgment, we are of the opinion that an order suspending the aforesaid services indefinitely is impermissible.”

Coming down strongly on the use of Sec 144 the judges said:

“The power under Section 144, Cr.P.C., being remedial as well as preventive, is exercisable not only where there exists present danger, but also when there is an apprehension of danger. However, the danger contemplated should be in the nature of an “emergency” and for the purpose of preventing obstruction and annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed… The power under Section 144, Cr.P.C cannot be used to suppress legitimate expression of opinion or grievance or exercise of any democratic rights.”

But the judgement rejected the petitioner’s contention that the blockade meant that the “people of Kashmir were plunged into a communication blackhole and an information blackout.” Despite enough and more evidence that the internet shutdown completely crippled news media and suspended websites, hampered news gathering and rendered journalists dependent on artificial mechanisms like a centralized media centre with limited internet access, the order said:

“Without such evidence having been placed on record, it would be impossible to distinguish a legitimate claim of chilling effect from a mere emotive argument for a self-serving purpose.”

The net result of this order was that the Internet ban continued. There was nevertheless a relaxation, in terms of restoration of the 2G lower broadband speed, or Internet kiosks maintained by the Government, and the introduction of ‘whitelisting’, first with around 150 sites that were permitted, with more slowly added on. No mainstream news media were in the list.

According to research monitoring the whitelisted sites, by February 14, 2020, around a thousand sites were added to the list, but even this was hardly of any use and several sites were non-existent URLs or names misspelled. As this research into the whitelisted sites pertinently asked:

“Who chooses these websites?”

“What is the methodology to choose the websites?”

“What is the rationale of choosing 2G speed and banning VPN usage?”

“Why even whitelist?”

FMP petition: The COVID-19 lockdown deep sea

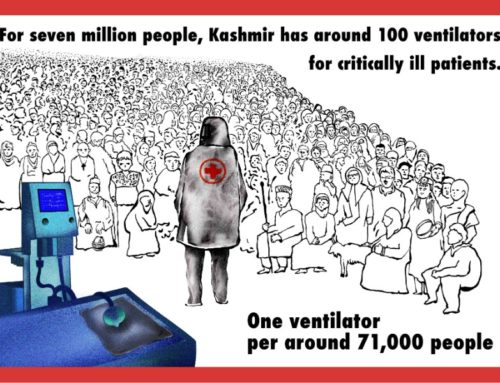

In any event, the phase-wise restoration of landlines and broadband and the continuing slowdown of the internet had disastrous implications for health workers and doctors dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite pleas that internet access was crucial to keep abreast of health developments to understand the nature of the virus and provide timely and effective healthcare to patients, the courts continued to remain obdurate. Another Writ Petition filed by the Foundation for Media Professionals (FMP) in March 2020 said that the internet slowdown had “deprived the people of their right to access healthcare, education, livelihood, justice and information during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

On May 11, 2020, the Supreme Court ordered that a Special Committee consisting of the Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, Secretary, Department of Telelcom and the Chief Secretary of the Union Territory of J&K will meet to “decide whether the internet slowdown in J&K was necessary and proportionate after balancing competing concerns of terrorism and human rights.”

On May 16, the FMP wrote to the Special Committee to “pay heed to the Supreme Court’s holding that internet restrictions are proportionate only if they are geographically and temporally limited.” The FPM said that blanket orders to slow down the internet could not be issued without providing specific reasons. Besides, internet restrictions could not be a tool to address terrorism, the FMP reiterated.

The FMP filed a contempt petition before the Supreme Court since the special committee was not formed as per the directive of the Apex Court. However, on June 24, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), in an affidavit, said that a special committee was constituted to look into the issue of restoring 4G internet in J&K and decided against resuming full services.

In an affidavit filed earlier this week, in response to contempt petition against the J&K administration, the MHA said: “Based on a considered and wide-ranging assessment of the prevailing situation in this sensitive region, the committee arrived at a decision that no further relaxation of restrictions on internet services, including 4G services, could be carried out at present.”

And so it goes on. In this miasma of bureaucratic strangleholds, what remains is the denial of the right of people of the valley to get online, to reach out to their near and dear, to join virtual classrooms or access course or job applications, to access the latest health bulletins and to speak out about their issues. This online silencing and invisibilising, which started out as a government’s collective policing to curb all manner of expression, including expectations of protest and resistance, is digital punishment in the extreme.

References

- (4 September 2019) A two-member team from the Network of Women in Media, India (NWMI) and the Free Speech Collective (FSC), comprising Laxmi Murthy and Geeta Seshu, visited the Valley between August 30-September 3,2019, and met more than 70 journalists, correspondents, editors of newspapers and news-sites in Srinagar and south Kashmir, members of the local administration and citizens. Our report entitled “News Behind the Barbed Wire: Kashmir’s Information Blockade”. FreeSpeechCollective . Retrieved from https://freespeechcollective.in/2019/09/04/news-behind-the-barbed-wire-kashmirs-information-blockade/

- Report from Software Freedom Law Centre, Retrieved from https://internetshutdowns.in/

- R.Kracekumar (21 February 2020), “1000 more whitelist sites in Kashmir, yet no Internet”.Retrieved from https://kracekumar.com/post/190951734050/1000-more-whitelist-sites-in-kashmir-yet-no/

- IFF (May 2020), “FMP approaches Special Committee established by SC for restoration of 4G internet in J&K”, Internet Freedom Foundation. Retrieved from https://internetfreedom.in/fmp-approaches-special-committee-established-by-sc-for-restoration-of-4g-internet-in-j-k/

- Hindustan Times (25 July 2020). ‘No relaxation in J&K 4G curbs yet, Centre tells SC’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/no-relaxation-in-j-k-4g-curbs-yet-centre-tells-sc/story-RILP9SPhDPMs8shbFdThrM.html

About the Author: Geeta Seshu is a journalist and co-editor of Free Speech Collective. She is based in Mumbai, India.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.