Tales of a Vanishing River

Notes on Sand Mining in Kashmir

Basim-U-Nissa and Salik Basharat

Sand-mining is arguably one of the prime sources of environmental degradation in the world. More than 40 billion metric tons of sand is extracted every year, and over 50% of that is consumed by the construction industry. In the last few decades, several developing nations across the globe have co-opted rapid urbanisation into their national development policies. The foreseeable detrimental impact of these changes on the environment has been neglected. Urbanisation has been seen as a sure marker of ‘progress’. Urbanisation is achieved by standing upon the shoulders of the modern construction industry which depends on concrete prepared using sand. It’s no surprise then that sand is extracted at a large scale. India, a country that has obsessively focused on building urban spaces since the turn of the century, is the 2nd largest producer of concrete in the world and one of the leading extractors and consumers of sand.

Riverbed mining is a major form of sand extraction. According to a report by the Geological Survey of India, not only does it threaten the health and biodiversity of river systems, unchecked riverbed mining as it currently happens in India, has the potential to lead to the depletion of groundwater resources causing severe scarcity of river water, affecting irrigation and potable water availability all across the country. Unfortunately, despite these dire warnings, many of India’s rivers, such as the Sutlej, Baes, Ganga, Yamuna, Narmada, and Cauvery etc. are exploited unceasingly for river-bed sand.

In Kashmir, the primary casualty of this anthropocentric exploitation has been the Jhelum river, a 774 km long tributary of the Indus that flows right through the valley, physically and historically, and houses its sand mining industry. Whether due to the presence of an eco-spiritual heritage or Kashmir’s political instability or a mix of both, river-bed mining in Kashmir has traditionally obeyed the golden formula of harmonious natural living – which is, assuring that the rate of human-induced mineral extraction is always much lower than the rate of natural mineral replenishment. The sand extraction process in Kashmir has predominantly been a manual activity carried out by inhabitants from villages like Kakapora, Litter, and Sangam etc., located alongside the bank of river Jhelum. More recently, with a rise in the demand for urban spaces, a disregard for this age-old practice has seeped in.

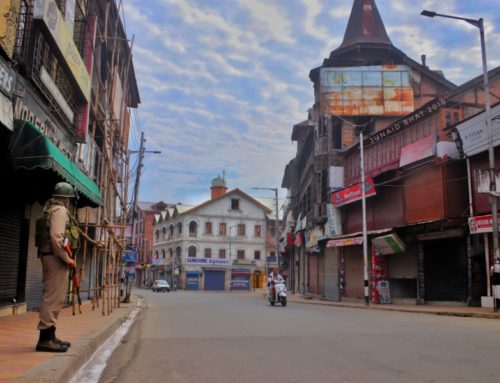

Almost instantaneously, under the gambit of urban development, the valley has witnessed a rise in housing projects and other concrete based construction activities. Just recently, on the 17th of July, the administrative council of J&K led by Lt. Governor G.C. Murmu sanctioned a proposal for the adoption of J&K Housing, Affordable Housing, Slum Redevelopment and Rehabilitation, and Township Policy, 2020 which sets an initial target of constructing 1 lakh housing units over the next five years. In a similar move, amendments have also been approved to the Control of Building Operations Act, 1988 and The Jammu and Kashmir Development Act, 1970 to allow a special dispensation for carrying out construction activities in strategic areas, which enables the government to notify any area as an area of strategic interest for the armed forces and then carry out construction activities as they deem fit . And as mentioned earlier, construction demands sand. The present day sand mining industry in Kashmir employs an ever increasing number of workers, around 1.5 lakh from all over Srinagar, Baramulla, Shopian, and several other districts who benefit economically from sand extraction and transportation activities. The three main categories of employers for this work are mining companies approved by the government, sand syndicates or mafias, and native individuals/families engaged in small scale traditional mining.

The mineral extraction and allocation laws abided by the Department of Geology and Mining (DG&M) of Kashmir seem to be non-partisan and environmentally conscious on paper, but the story on ground is not reflective of the promise of these laws.

Sand Mining in Kashmir before August 5, 2019

The DG&M, which is the regulatory body in charge of mining activities in Kashmir, has failed for years in curbing mineral exploitation. As per a report by the Tribune, the DG&M loses INR 300 crores annually to illegal mining of riverbed materials. Besides the excessive extraction of riverbed material at designated mining blocks, mining was carried out at locations that were not listed and auctioned as mining sites. Machines were increasingly employed for extraction by politically well-connected contractors even though the Department of Irrigation and Flood Control (DI&FC) had laid emphasis on extracting materials manually. The DG&M and DI&FC were not only exposed to threats and political patronage used by the sand mafia, but also complained of receiving little support from the police.

In a bid to curb illegal sand mining, a blanket ban on mining was imposed by the J&K High Court in 2017 and was executed by district administrations across Kashmir. In its order, the High Court had stated that illegal mining was carried out in contravention of the Mines and Minerals Development and Regulation Act, 1957, the J&K Minor Mineral Concession Storage, Transportation of Minerals and Prevention of Illegal Mining Rules, 2016 [SRO 1065 (Dated 31.03.2016)] and several other rulings of the Supreme Court of India and the J&K High Court. Consequently, there was no existing valid mineral block allotment post-February 28, 2019 as per the SRO 93 of 2019 on February 1, 2019 of the Industries and Commerce Department of the J&K Government.

In conjunction with this policy, the Additional Deputy Commissioner of Pulwama district – exercising powers envisaged under Section 133 of J&K Criminal Procedure Code – imposed a blanket ban on the unlawful extraction and mining of minerals from rivers, nallahs, water bodies, tributaries and offshoots in the district, and soil from the Karewas, carried out in any manner. For the said purpose, the district administration also constituted area-specific task forces in order to ensure that guidelines were adhered to. The task forces were authorized to arrest any person operating earth movers and trucks and seize the machinery used. The order also called for initiating legal action against habitual offenders, and identification of the main sponsors, patrons and networks facilitating the illegal mining.

Despite repeated efforts by governmental authorities, illegal mining continued unabated. Concerns over the inaction of the authorities were raised by the residents of the catchment areas of Jhelum with the Deputy Commissioner, Srinagar, regarding the “multi-crore sand and clay scam” in river Jhelum in 2018. The DC had directed the DI & FC to conduct an inquiry into the matter and furnish a detailed report. However, the fate of the inquiry is still unknown, and no such report is traceable. Officials in the DC office claimed that ordering the probe “was an eye-wash”, considering which locals allege that the involved brokers continued unlawful extraction as the authorities avoided acting against them.

In many other reports about the rampant continuation of illegal mining, locals allege that there is a nexus between the mining mafia and the relevant government departments. For example, residents of Kupwara alleged that illegal sand and stone extraction in Nallah Mawar was being done by influential people at the behest of the district administration. Locals alleged that the mining mafia works in tandem with the relevant authorities, stating that, “It is surprising that just before any officials visit the site the extractors leave the spot.”

Ecological Ramifications

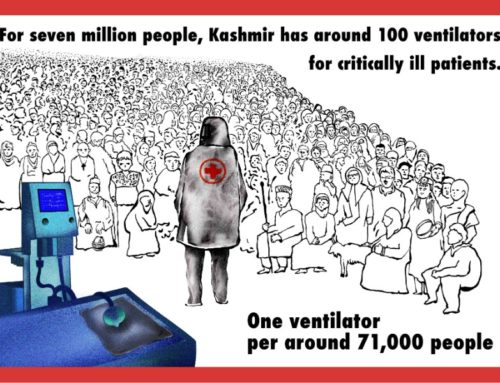

Defiled in the past two decades by rising urban populations and pollution, increased deforestation, and changing land use patterns along its floodplains, the local rivers have been under grave threat of mechanised sand extraction that will further ravage the river system. The removal of vegetation and destruction of soil profiles have ruined habitats above and below the ground and have led to a decline in fauna. Fish spawning of certain indigenous species such as the Schizothorax species of fish, known locally as kaeshirgaad, has decreased drastically due to this exploitation. The fish catch per unit of the famed trout of Kashmir too has been dwindling over the years. As per a study conducted by Prof. Farooz Ahmad Bhat of Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Agriculture Sciences (SKUAST), the lifting of sand, boulders, pebbles and stones from the riverbed is a prime cause of this decline.

Major lakes that are part of the Jhelum river basin, such as the Wular, are also facing threats from increased siltation due to river-bed mining. River channel widening has caused a shallowing of stream beds, and the riverbed has dried up in multiple locations due to an increased exposure to solar radiation. In several areas along the Jhelum riverbed mining has increased initial and premature failure of irrigation wells.

The troubled hydrological functionality of the Jhelum floodplains is tested further by new habitations and concrete structures that are now coming up along its banks. All of these constructions are perpetually in immediate danger of flooding. As per a 2018 report by the Central Water and Power Research Station, “The dredging, desilting/sand mining of the main channel of Jhelum from upstream to Asham is not advisable and may cause difficulties for the flood management.” Concomitantly, illegal mining carried out in Jhelum poses a threat to the Lower Jhelum Hydel Power Project, Uri besides endangering the pre existing embankments along the river. It’s almost as if the devastating Kashmir floods of 2014, in which at least 300 people lost their lives and millions were displaced, wasn’t enough of a warning for the government to tread with caution on the tightrope of urban construction.,,

Sand Mining in Kashmir after August 5, 2019

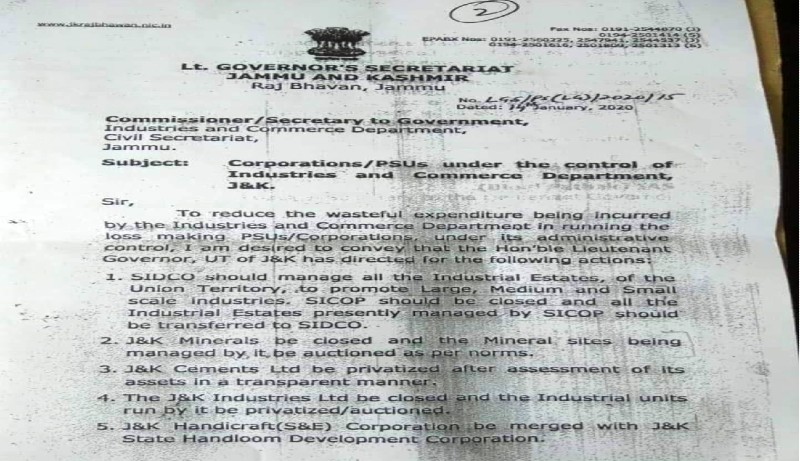

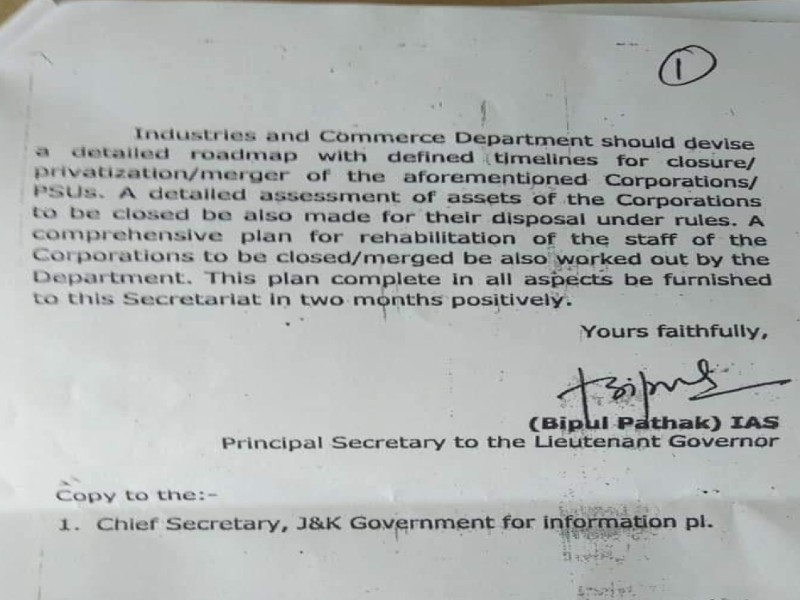

In the aftermath of the de-operationalisation of Article 370, the J&K administration-initiated e-auctioning of minor minerals and riverbed materials for the first time in its history. The stated objectives of the move were to put in place a transparent process for the allocation of the mineral blocks, and to boost the revenue generated by the DG&M. The authorities were also considering granting ‘Short-term Permits’ to organizations like Border Roads Organization, National Highway Authority of India, Central Public Works Department, and Jammu Kashmir Projects Construction Company in order to ensure that developmental work could be carried out seamlessly.

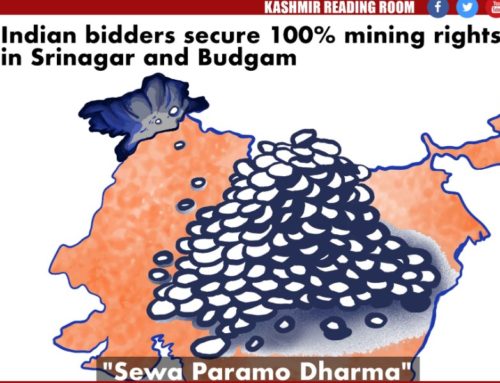

For the same purpose, the administration had identified over 260 mining blocks along the Jhelum alone. In January 2020, e-auctioning of over 150 land banks in Kashmir was initiated. Most of these mining blocks, that have since been allotted, are concentrated in South Kashmir, with 36 in Pulwama alone. However, the process of allocation adopted by the administration is questionable.

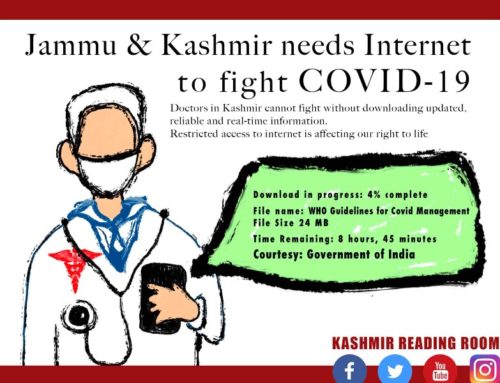

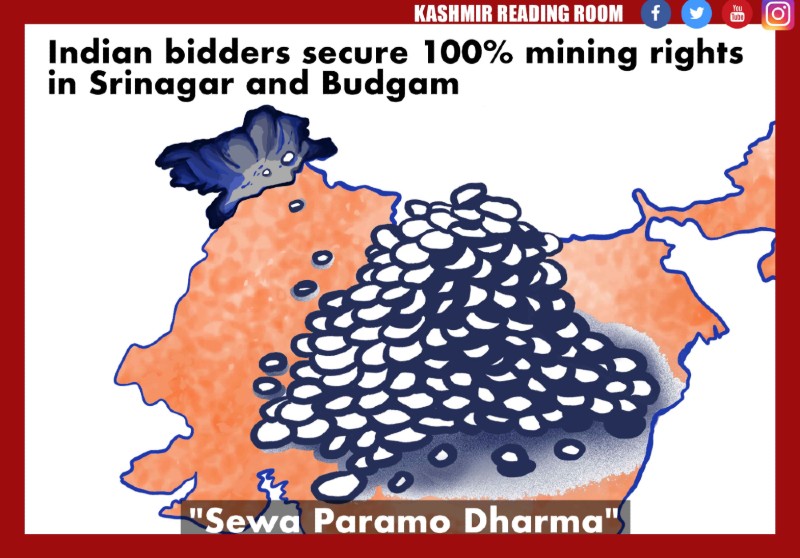

E-auctions were publicized in September 2019 when the internet ban, which had been imposed after the amendment of Article 370, was still in place. Applications were invited from potential bidders in December 2019 and early January 2020 while internet connectivity had still not been restored in the Valley. The government advised local businessmen to bid from the government’s internet facilitation centers while some contractors were forced to move outside the union territory, amidst travel restrictions, to be able to access the internet and register their bid. Despite this, non-local bidders have been able to capture a majority of the auctioned mineral blocks and locals are left complaining about restricted access to the bidding process.

Shakir, a local contractor, who managed to bid for three spots, even though unsuccessfully, summarizes the predicament of the local contractors who blame the internet ban for their losses:

“First, they banned the internet. And then they issued tenders for mining rights. Had they not been ill-intentioned, they would’ve waited for the restoration of the internet”

The centrality of the access to internet to the bidding process can be assessed from the following data (table 1). Approximately, 73% of successful bidders across six districts are non-locals. The ratio is most bleak in districts like Srinagar and Bandipora which were among the first ones to be earmarked for e-auctioning. Mir and Khan, the only successful local bidders in Bandipora, speak of the bidding process – “During bidding, our computer showed us the sign ‘please wait’ after providing a new rate and till the page refreshed, the tenders were won by outsiders.” The percentage of successful local bidders is the highest in Kulgam where the auction process was completed most recently (ending June 2020) when local businessmen had relatively better internet connectivity.

Table 1: District-wise percentage of successful bidders by Residential Status

| District | Percentage of successful bidders local | Percentage of successful bidders_non-local |

|---|---|---|

| Srinagar | 0.00% | 100.00% |

| Bandipora | 5.26% | 94.74% |

| Anantnag | 20.00% | 80.00% |

| Baramulla | 31.58% | 68.42% |

| Budgam | 42.86% | 57.14% |

| Kulgam | 66.67% | 33.33% |

| Average | 27.73% | 72.27% |

Of the minimum reserve bids (see annexure 1). Similarly, the average successful bid per block across the 97 blocks that data is available for is a whopping 81.6 lakhs (table 2). In Pulwama, for example, the highest bid for a block went up to 3.25 crores as compared to 77 lakhs during the last auction. Local bidders also allege that non-local contractors purposely increase the bidding amount when applying for a block. Yousuf, a local contractor, contextualizes the sharp increase – “Until now the rate per block would not be much. Some of the blocks would cost aroIn addition, opening up of mining leases for non-locals has led to a radical increase in the highest successful bid amount, as such, rendering locals incapable of matching the high bids. For example, all the bids in Srinagar were won by non-local contractors. The sum of highest bids made was 7158.6% more than the sumund Rs 1 lakh”.

Table 2: Average successful bid amount per block by district

| District | Number of Blocks | Corresponding Sum of Highest bids | Average Bid Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulwama | 12 | 178200000 | 14850000.00 |

| Kulgam | 15 | 157670000 | 10511333.33 |

| Anantnag | 15 | 156577000 | 10438466.67 |

| Budgam | 7 | 46711000 | 6673000.00 |

| Baramulla | 38 | 201500000 | 5302631.58 |

| Srinagar | 10 | 50810000 | 5081000.00 |

| Total | 97 | 791468000 | 8159463.92 |

The closure of the bidding process, however, does not ensure the allocation of mining blocks to successful bidders. It is to be followed by a Letter of Intent – provided by the concerned district magistrate, an environmental clearance from the State Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority of J&K, a mining plan approved by the DG&M, and a consent to operate (CTO) obtained from the Pollution Control Board (PCB).In connection with the recent allocations made by the DG&M, the Deputy Director of the Department, Dr. Amarjit Singh Sodhi assured that, “All the firms are bound to get Non-Objection Certificates (NOC) from all the departments falling under ministry of environment, forest, ecology and environment. Mining sites will be properly checked and [then] will be handed over to the firms.”

However, it has been noted that mining operations in the blocks recently allotted to non-local contractors are already underway even before obtaining environmental clearances. According to residents of Lassipora, heavy extraction vehicles have been deployed in Nallah Rambiara. These reports have also been confirmed by the regional Director of the PCB who claims to not have received any applications for the requisite CTO yet.

These illegal mining operations are being conducted well under the nose of the District administration as Shahnawaz, a local contractor working on behalf of a non-local firm, Hari, claims – “We have all the documents and we are expecting EC [environmental clearance] soon. We have been allowed by the district administration to operate since we are supplying material for government works – NREGA and PMGSY. All the officials including the DC of Pulwama knows we are extracting material. We are now waiting for EC which will come soon.” In absence of EC, even if awaited, any mining activity conducted is illegal.

The allocation of mining blocks to non-locals has been widely criticised especially as J&K is already grappling with high unemployment rates. Abdul QayoomWani – Chairman of Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Forum, while calling for the immediate cancellation of contracts allotted to non-locals claimed that the government manipulated the bidding process in favour of the non-local firms in order to render bonafide residents of the valley jobless. The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce also registered their objections with the allocations, referring to the policy as “alarming and against public interest”. Critical voices were also heard from across the political spectrum. Members of Hurriyat alleged that the process was designed to benefit the non-locals and the COVID pandemic was being used to exploit J&K’s natural resources. CPI(M) leader, Mohammad Yousuf Tarigami also sought the cancellation of the contracts given to non-locals.

Economic Displacement in the Traditional Industry

In the wake of issuing e-tenders for mining blocks, the livelihood of local laborers involved in manual extraction of sand has, in fact, been obliterated by the recent mining policy. Traditionally, most sand and stone extraction in Kashmir was done manually. Typically, the laborers involved in extraction, dumping, loading and transportation of the materials were inhabitants of villages (like Kakapora, Litter, Lassipora and Sangam etc.) that are located along the banks of local rivers. Consequently, manual extraction of riverbed materials has been a predominant occupation in these areas for generations and continues to be the primary source of livelihood for many families even today. An estimated 1.5 lakh families are dependent on the industry in Kashmir.

In this context, the revision in the mining policies comes as a direct threat to the subsistence of these people. Speaking of the plight of the sand digger’s community, Sharik says –

“We (contractors and businessmen) might still manage. Traditional sand diggers are at the verge of begging. Someone who has earned his living from sand digging all his life can’t pick-up a new vocation when he is old.”

As a result, sand diggers from various parts of Kashmir have been holding protests and have demanded that the Lieutenant Governor personally looks into the matter. However, no respite has been provided to the marginalized group yet.

Kashmiri Eco Spiritual Legacy

The disempowerment of local communities in Kashmir is not limited exclusively to the realm of politics. A systemic patronage by the central government of India is usurping the powers of indigenous people over their land and resources. The inapplicability of the Forest Rights Act that empowers tribal communities in J&K, the conversion of the Forest Department of J&K into a government-owned corporation, the opening up of local quarries and land banks to non-local competition, government sponsored allocation of land to potentially hazardous industries, and other recent developments point towards a centralisation of authority and an institutionalized marginalisation of local communities. This concentration of authority brings with it a homogenising force which neutralises any alternate opinions.

The proposed model for development in Kashmir is a replication of the same models that have been long implemented in India’s peripheries, and have led to a blatant exploitation of resources, violation of rights and interests of local communities and have completely disregarded traditional knowledge systems and practices. The marginalisation of the Adivasi community in India due to land alienation, loss of access and control over forests, enforced displacement due to development projects and lack of proper rehabilitation bears a testament to the failure of this mindless implementation of western developmental model in local contexts.

An eco-spiritual existence has been one of the pillars of the cultural landscape of Kashmir. Evidence for this can be found in the literature and architecture of Kashmir, in its intellectual and spiritual life, and even in local parlance. The creation legend of Kashmir itself speaks of a valley through which the Goddess Parvati in the form of the sacred purifying river Vitasta – also known as the Vyeth, the Hydaspes, the Jhelum – flows. Baba Bulbul Shah’s mosque, the shrine of Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani, Kheer Bhawani, Rinchan Shah’s Mazaar, the Batyar temple, and several other religious structures are built along the Jhelum indicating its importance in Kashmir’s religious imagination. Nund Rishi’s 14th Century ecological wisdom reverberates through the halls of Kashmiri experience and into our modern dictionaries – “aanposhiteli, yeli wan poshi (nurture nature, for nature nurtures)”, he says, offering great insight into the ways of nature. Even Habba Khatoon, before forsaking material life, cleansed herself at Panda Chok in the Jhelum river for the river is said to purify all sins.

There is abundant knowledge in our native experience from which we can draw inspiration and caution before fiddling with traditional modes of living. Yet, despite centuries of tradition and experience, a modern anti-culture called ‘progress’ which has wreaked havoc not only in the social and natural spaces of India, but the entire world is slowly burrowing itself into the valley. The defunct ecologically conscious laws and rising unmanaged urban construction hatched onto a canvas next to the de-operationalisation of Article 370 and the reassurance given to non-local mining companies and investors places before our eyes a bleak painting of a possible ecological, cultural, and social disaster. The tenets of environmental colonialism all check out. The creation of a competitive sand market will peak the interest of urban construction companies and lead to a greater exploitation of river-sand. This river-sand will be used to create modern compounds, complexes, housing and other structures to accommodate the increasing urban population and new settlers, inevitably displacing local communities, livelihoods, and their cultural experiences. The floodplains of the Jhelum will suffocate, and this will not only destroy fertile land and ecosystems, but also put the constructed buildings and populations at great existential risk from flooding. The irony is that the very structures that were built at the expense of environmental exploitation will be consumed by the exploited environment.

One might be inclined to believe then that to be ‘developed’ is to develop endlessly. To sustain expansion is to disregard history and the wisdom of nature and pave a path for endless exploitation, until, of course, there is nothing left to exploit. For the politically tyrannised people of Kashmir then, what does India’s environmental colonialism and capitalist expansion hold in its future? Local Kashmiri wisdom, exposing itself in the poignant words of boatman, Noor Mohammad Pakhdoomi, giggles at this concern, ‘The entire Valley can be brought to its knees, but the Jhelum will always have its own rules.’

Annexure 1: List of successful bidders

| Block Number | District | PID of successful bidder | Residential Status | Minimum Reserve Bid | Highest Bid amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Anantnag | sdmn_004 | non-local | n/a | 1619000 |

| 3 | Anantnag | sdmn_005 | non-local | n/a | 1339000 |

| 2 | Anantnag | sdmn_009 | local | n/a | 9128000 |

| 10 | Anantnag | sdmn_014 | non-local | n/a | 4500000 |

| 12 | Anantnag | sdmn_015 | non-local | n/a | 7658000 |

| 18 | Anantnag | sdmn_017 | non-local | n/a | 19359000 |

| 6 | Anantnag | sdmn_020 | non-local | n/a | 2001000 |

| 11 | Anantnag | sdmn_020 | non-local | n/a | 16989000 |

| 4 | Anantnag | sdmn_022 | non-local | n/a | 16330000 |

| 19 | Anantnag | sdmn_024 | non-local | n/a | 9655000 |

| 1 | Anantnag | sdmn_026 | local | n/a | 10339000 |

| 17 | Anantnag | sdmn_027 | local | n/a | 21577000 |

| 16 | Anantnag | sdmn_032 | non-local | n/a | 25585000 |

| 20 | Anantnag | sdmn_034 | non-local | n/a | 1188000 |

| 5 | Anantnag | sdmn_037 | non-local | n/a | 9310000 |

| 10 | Budgam | sdmn_002 | local | n/a | 13079000 |

| 4 | Budgam | sdmn_006 | non-local | n/a | 883000 |

| 1 | Budgam | sdmn_007 | non-local | n/a | 1315000 |

| 11 | Budgam | sdmn_009 | local | n/a | 11733000 |

| 2 | Budgam | sdmn_015 | non-local | n/a | 3116000 |

| 3 | Budgam | sdmn_017 | non-local | n/a | 1006000 |

| 12 | Budgam | sdmn_033 | local | n/a | 15579000 |

| 20 | Kulgam | sdmn_001 | local | n/a | 5280000 |

| 9 | Kulgam | sdmn_003 | local | n/a | 3730000 |

| 29 | Kulgam | sdmn_005 | non-local | n/a | 45060000 |

| 3 | Kulgam | sdmn_008 | local | n/a | 1770000 |

| 6 | Kulgam | sdmn_010 | local | n/a | 1590000 |

| 27 | Kulgam | sdmn_011 | local | n/a | 28890000 |

| 11 | Kulgam | sdmn_012 | non-local | n/a | 6500000 |

| 16 | Kulgam | sdmn_014 | non-local | n/a | 9870000 |

| 28 | Kulgam | sdmn_017 | non-local | n/a | 19420000 |

| 26 | Kulgam | sdmn_021 | local | n/a | 14420000 |

| 17 | Kulgam | sdmn_028 | local | n/a | 5480000 |

| 10 | Kulgam | sdmn_029 | local | n/a | 1610000 |

| 30 | Kulgam | sdmn_034 | non-local | n/a | 1080000 |

| 25 | Kulgam | sdmn_035 | local | n/a | 6670000 |

| 21 | Kulgam | sdmn_036 | local | n/a | 6300000 |

| 7 | Srinagar | sdmn_013 | non-local | 70000 | 16220000 |

| 10 | Srinagar | sdmn_015 | non-local | 60000 | 200000 |

| 6 | Srinagar | sdmn_016 | non-local | 50000 | 3100000 |

| 8 | Srinagar | sdmn_020 | non-local | 80000 | 7800000 |

| 1 | Srinagar | sdmn_023 | non-local | 70000 | 190000 |

| 4 | Srinagar | sdmn_025 | non-local | 80000 | 10660000 |

| 3 | Srinagar | sdmn_030 | non-local | 80000 | 7200000 |

| 2 | Srinagar | sdmn_031 | non-local | 50000 | 210000 |

| 5 | Srinagar | sdmn_037 | non-local | 80000 | 4050000 |

| 9 | Srinagar | sdmn_037 | non-local | 80000 | 1180000 |

References

-

- The article shares its title with a book of humorous stories published by Earl Howell Reed in 1920. The title is reflective of the draining of the marshlands situated along the Kankakee River, at and around which the stories are situated. Today, the river is essentially a ditch.

- Torkington, S (5 October 2016). ‘India will have 7 megacities by 2030, says UN’. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/india-megacities-by-2030-united-nations/

- United Nations Environment Programme (2019). ‘Sand and Sustainability: Finding new solutions for environmental governance of global sand resources’. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved from http://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28163/SandSust.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Kohli, K (26 August 2013). ‘The Struggle Over Riverbed Mining in India’. International Rivers. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/blogs/257/the-struggle-over-riverbed-mining-in-india

- Bhat, S (12 February 2020). ‘Sandstorm’. KashmirLife. Retrieved from https://kashmirlife.net/sand-storm-issue-45-vol-11-223571/

- Hakhoo, S (15 April 2015). ‘J-K losing Rs 300 crore annually due to illegal and sand mining’. Retrieved from https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/archive/features/j-k-losing-rs-300-crore-annually-due-to-illegal-sand-mining-67920

- Ibid.

- The Kashmir Walla (7 July 2019). ‘Despite High Court ban, illegal extraction going on unabated in River Sindh’. Retrieved from https://thekashmirwalla.com/2019/07/despite-high-court-ban-illegal-extraction-going-on-unabated-in-river-sindh/

- The Kashmir Walla (7 July 2019). ‘Delhi High Court ban, illegal extraction going on unabated in River Sindh’. The Kashmir Walla. Retrieved from https://thekashmirwalla.com/2019/07/despite-high-court-ban-illegal-extraction-going-on-unabated-in-river-sindh/

- GNS (2 April 2019). ‘Blanket ban imposed on illegal extraction, mining of riverbed material in Pulwama’. Fast Kashmir. Retrieved from https://fastkashmir.com/2019/04/blanket-ban-imposed-on-illegal-extraction-mining-of-river-bed-material-in-pulwama/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Early Times Report (3 February 2019). ‘What happened to the sand mafia enquiry?’. early TIMES. Retrieved from http://earlytimesnews.com/newsdet.aspx?q=256211

- Shah, M (13 January 2019). ‘Illegal sand mining in Kupwara under the nose of authorities’. Greater Kashmir. Retrieved from https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/kashmir/illegal-sand-mining-in-kupwara-under-the-nose-of-authorities/

- The Third Pole (18 April 2016). ‘The troubled trout of Kashmir’. TheThirdPole. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2016/04/18/the-troubled-trout-of-kashmir/

- Shabir, Z. B (23 July 2019). ‘How illegal pursuit of riverbed material is threatening the habitat of Kashmir’s trout fish’. FreePressKashmir. Retrieved from https://freepresskashmir.news/2019/07/23/how-illegal-pursuit-of-riverbed-material-is-threatening-the-habitat-of-kashmirs-trout-fish/

- Parvaiz, A (17 February 2020). ‘Mining expands on Kashmiri rivers despite dire warnings’. The Third Pole. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2020/02/17/mining-expands-on-kashmiri-rivers-despite-dire-warnings/

- Kashmir Age (15 April 2020). ‘Illegal Sand Mining Threats Lower Jhelum Hydroelectric Project, Uri’. Kashmir Age. Retrieved from https://kashmirage.net/2020/04/15/illegal-sand-mining-threatens-lower-jhelum-hydroelectric-project-uri/

- SANDRP (8 June 2017). ‘Jammu and Kashmir Rivers Profile (Jhelum and Chenab Basins)’. SANDRP. Retrieved from https://sandrp.in/2017/06/08/jammu-and-kashmir-rivers-profile-jhelum-and-chenab-basins/

- The World Bank (2018). ‘Jhelum and Tawi Flood Recovery Project. The World Bank. Retrieved from http://jtfrp.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Task1_Report_Final.pdf

- Burke, J and Boone, J (11 September 2014). ‘Kashmir monsoon floods leave 460 dead and displace almost a million’. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/11/kashmir-monsoon-floods-million-displace-pakistan-india-aid

- Daily Excelsior (6 January 2020). ‘For transparency, e-auctioning of minor mineral blocks initiated for first time in J&K’. DailyExcelsior.com. Retrieved from https://www.dailyexcelsior.com/for-transparency-e-auctioning-of-minor-mineral-blocks-initiated-for-first-time-in-jk/

- KNT News Desk (24 June 2020). ‘e-auction of sand blocks go to non-local contractors in Kashmir ‘Move will generate more revenue’. Kashmir News Trust. Retrieved fromhttp://kashmirnewstrust.in/2020/06/e-auction-of-sand-blocks-go-to-non-local-contractors-in-kashmir-move-will-generate-more-revenue-2114/

- Zargar, A (5 February 2020). ‘With Article 370 Gone, Locals Lose Majority Bids for Sand Extraction in Kashmir’. Newsclick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/Article-370-Gone-Locals-Lose-Majority-Sand-Extraction-Kashmir

- Supra note 243.

- This is an excerpt from an interview conducted by the authors. Names have been changed to maintain anonymity.

- Also see annexure 1.

- Supra note 243.

- Percentage has been calculated using numbers from the following reports stating that only one out of the 20 blocks auctioned was secured by local contractors – https://kashmirlife.net/sand-storm-issue-45-vol-11-223571/

- In absence of detailed data for Baramulla district, percentages have been quoted from the following report stating that 26 out of 38 blocks auctioned went to non-locals – https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/business/non-local-firms-bag-majority-of-mineral-extraction-contracts-in-kashmir/

- Supra note 262.

- Ibid.

- In absence of detailed data for Pulwama, average bid amount has been calculated using the data quoted in the following report – https://kashmirlife.net/sand-storm-issue-45-vol-11-223571/

- In absence of detailed data for Baramulla (see annexure 1), average successful bid amount per block has been calculated from the following report stating that 38 blocks in Baramulla fetched 20.15 crores – https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/business/non-local-firms-bag-majority-of-mineral-extraction-contracts-in-kashmir/

- Supra note 262.

- Malik, I. A (25 February 2020). ‘Environmental hazards of sand mining wars’. The Kashmir Walla. Retrieved from https://thekashmirwalla.com/2020/02/environmental-hazards-of-sand-mining-wars/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CExcessive%20instream%20sand%20mining%20is,people%20make%20of%20the%20river.

- Zargar, A (30 June 2020). ‘J&K: New Contractors Begin Extraction on Mineral Blocks Without Environmental Clearance’. Newsclick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/Jammu-kashmir-new-contractors-begin-extraction-mineral-blocks-without-environmental-clearance

- Ibid.

- Kashmir Pen (27 June 2020). ‘Allotment of sand extraction contracts to non-locals making locals jobless: QayoomWani “Cancel all such contracts, won’t allow it at all’. Kashmir Pen. Retrieved from https://www.kashmirpen.com/allotment-of-sand-extraction-contracts-to-non-locals-making-locals-jobless-qayoom-wani-cancel-all-such-contracts-wont-allow-it-at-all/

- Outlook News Scroll (7 June 2020). ‘Revoke decision giving mining contracts to non-locals: Tarigami’. Outlook News Scroll. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/revoke-decision-giving-mining-contracts-to-nonlocals-tarigami/1879357

- Ibid.

- Supra note 243

- Round brackets represent clarifications added by the authors

- Kalla, K. L (1985). The Literary Heritage of Kashmir. Mittal Publications: Jammu & Kashmir

- Dutta, P (17 October 2019). ‘Eternal Witness of Kashmir Valley: Tracing the Jhelum River’.Sahapedia. Retrieved from https://www.sahapedia.org/eternal-witness-kashmir-valley-tracing-jhelum-river

- In order to avoid publishing the names of human subjects, PIDs are used. PID is a unique code assigned to a person/entity irrespective of the district. As such, a bidder will have the same PID across different districts.

- The residential status has been assigned on the basis of name and address of the successful bidders.

Annexure 1

Annexure 2

About the Author: Basim-U-Nissa is a Research Fellow at the Trivedi Center of Political Data, Ashoka University. She is interested in the study of state repression, political violence and the media.

Salik Basharat is an MA student at Ashoka University studying English and Philosophy. His areas of interest include environmental ethics, Kashmiri mysticism, 19th-century philosophy, cultural studies, magic realism and poetry.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.