The State Of Bakarwal Tribe In Times Of Covid Crisis

By Afreen Faridi

The erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) recognized 12 Scheduled tribes within its territory, numbering more than 140,000 individuals who comprise 11.9% of the total population as per the Population Census of 2011. Over 90% of the tribal populace follows the religion of Islam in this region. These tribal communities are one of the most vulnerable groups in the subcontinent, having endured the vagaries of the partition, conflict, climate change, deforestation, neo-liberalization, and now a global pandemic, leading to their increased marginalization within the modern nation-state. Of the twelve tribal groups, the Bakarwals are the second largest in number, after the Gujjar tribe. The Bakarwals and the Dodhi-Gujjars comprise one of the largest transhumance communities in South-Asia. They undertake bi-annual migration between the high-altitude Himalayan pastures in Kashmir and Ladakh in summers, to the plains and the Pir-Panjal range in the Jammu region.

Such migrations are integral to the social, economic, and cultural milieu of these two communities, who have traditionally reared livestock as their primary source of livelihood. Hence, they refer to themselves as khanabadosh or nomads. Since Bakarwals and Gujjars are mostly Muslims in India Administered Jammu & Kashmir (IAJK), such a mode of existence draws its sanctity as – Sunnah or inspiration from the Prophet, making the community loathe to any change in their traditional work practices.

The State of Bakarwals Post-Partition

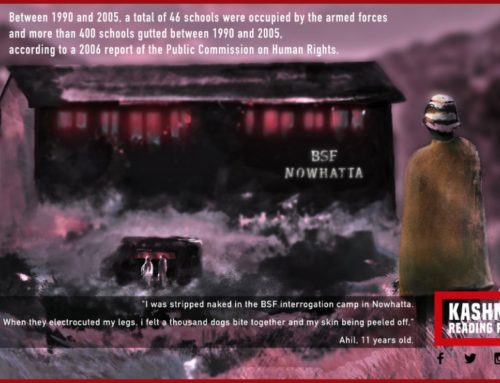

The nomadic tribes have always had an antagonistic relationship to the modern state, which has actively criminalized, exploited, and encroached upon their territories through the colonial project. After the end of British colonial rule in the Indian subcontinent, the independent Indian state took up its rein and expanded the colonial project in this Himalayan state of J&K. The brunt of partition in 1947 was faced by the Muslims of Jammu, a predominant tribal populace, when the erstwhile Maharaja of the Princely State, with the help of RSS1Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a Hindu Nationalist Organisation , exterminated the local populace through a systemic genocide to engineer a demographic change in the Jammu region and reduce Muslims to a minority2Naqvi, S. (10 July, 2016). The killing fields of Jammu: How Muslims become a minority in the region. Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/811468/the-killing-fields-of-jammu-when-it-was-muslims-who-were-eliminated . Four successive wars with Pakistan- 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999, along with the Sino-India wars, carved up traditional communitarian lands of the Nomadic tribes between the three nation-states of India, China, and Pakistan. The trifurcate claims of ownership over the region led to the establishment of impenetrable borders, drastically reducing the pastoral lands which the Bakarwals accessed for rearing their flock. The access to traditional pastures was further aggravated by the rise of the popular uprising in Kashmir during the late 1980s, when the colonial state of India, used military occupation to capture swathes of meadows, restrict and close access to traditional migratory routes via mountain passes, and forced recruitment of tribes as porters and guides, while usurping their livestock at will3Parvaiz, A. (16 June,2014). Military activities destroy Kashmir’s highland pastures. thethirdpole.net. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2014/06/16/military-activities-destroy-kashmirs-highland-pastures/ .

Amidst contestations of nationhood and citizenship between the people of Kashmir and the Indian state, the Bakarwals have continually lacked representation over claims of ownership of land and resources.4Faridi, A. (Forthcoming).’ Child Labour in a Pastoral Tribe of Jammu and Kashmir: Impact of Spatiality within the State of Conflict.’ In A. Posso, Child Labor in the Developing World. Palgrave. (Forthcoming) The land reforms of the 1950s in IAJK, did not benefit the Nomadic tribes, who, to their own detriment, did not recognize private property rights and did not lay claim over communitarian lands. It was only in 1991 that the Bakarwals were recognized as scheduled tribes by the state, which then accorded affirmative action to uplift them. A social milieu that existed outside the norms of private property, the nomadic tribes have been historically disenfranchised as they did not possess the documents requisite for the nation-state to acknowledge individuals as its ‘permanent residents’ in IAJK. Furthermore, state forest officials, in the absence of Forest Rights Act (2006), have been notorious of denying the nomadic tribes access to forests lands, extorting them, and evicting them from their Deras which granted the Bakarwals proximity to pastures, water bodies and minor forest produce required for their daily sustenance. Hence, even after being recognized as Scheduled Tribes, state policies of affirmative action in the areas of education and employment could not be accessed by the members of the Bakarwal tribe. In addition to political conflict, state-led neo-liberalization and globalization have further marginalized Bakarwals by forcing them to engage in the market-economy – an alien mode of production until recently for the nomadic tribes. Limited access to credit, modern veterinary medicine, along with increased competition from imported wool and low auction rates in times of high inflation have had a detrimental impact on the traditional work practices of this nomadic populace. As per an unpublished survey, about 39% of nomads have given up migration5Parvaiz, A. (16 January 2020). ‘The tribal population of Jammu and Kashmir cries foul about the non-implementation of the Forest Rights Act.’ Mongabay. Retrieved from https://india.mongabay.com/2020/01/tribal-population-of-jammu-and-kashmir-cries-foul-about-the-non-implementation-of-the-forest-rights-act/ , owing to continued marginalization within IAJK, the Bakarwal community bears the highest incidence of illiteracy, child mortality, child labour and marginality of work amongst all social groups in the region.

The socio-economic status of the Bakarwal tribes got a major hit after the rise of ethno-nationalism and the propagation of sectarian politics in IAJK, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the Indian Parliamentary elections in 2014 and formed a coalition with the Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party to form the regional state government in IAJK.6Chakravarty, I (29 June 2019). ‘Why the BJP’s bid for delimitation in Jammu and Kashmir is being viewed with suspicion.’ Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/928324/why-the-bjps-bid-for-delimitation-in-jammu-and-kashmir-is-being-viewed-with-suspicion As a result, the bodies of the Muslim nomads became sites of communal violence, including sexual assaults.7Bhatnagar, G. (29 April 2018). ‘Kathua Case: A Part of Continuing Oppression of Pastoral Communities’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/women/kathua-gangrape-murder-bakarwals-pastoral-community The lowest moment being the 2018 sexual assault and murder of a minor girl from the Bakarwal tribe in Kathua, with political representatives of the BJP coming out in support of the accused.

Such attacks by Hindutva non-state actors aim to stop Bakarwals from settling in the Hindu-dominated Jammu plains during winters. Furthermore, cow-vigilantes attack the tribes during migration, a tactic to terrorize and prevent Muslims from rearing cows and other milch animals, to wrest control of the dairy and meat industry from these nomads. The period leading up to the year 2019 witnessed the aggregation of the political, economic, and social forces, inspired by the vision of the Hindutva state, to further exclude the Bakarwal community from their claims over ownership of land and resources.8Faridi, A. (Forthcoming).’ Child Labour in a Pastoral Tribe of Jammu and Kashmir: Impact of Spatiality within the State of Conflict.’ In A. Posso, Child Labor in the Developing World. Palgrave. (Forthcoming)

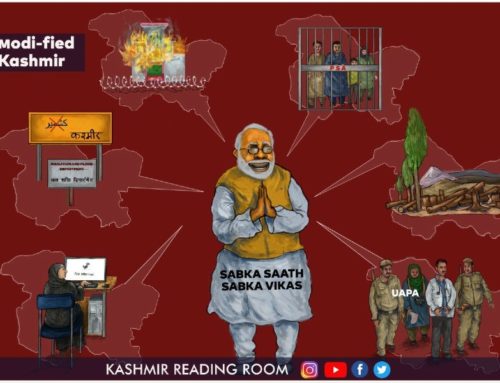

The State of Bakarwals After Invalidation of Article 370

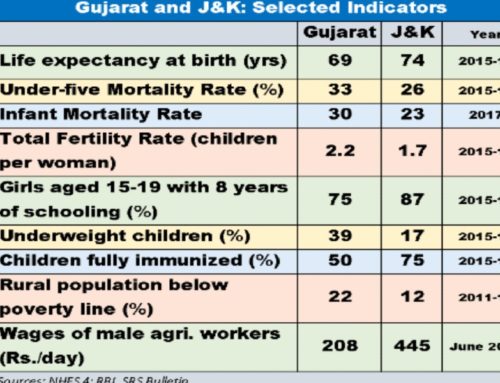

On August 5, 2019, the Indian government unilaterally revoked the limited autonomy of IAJK, a special status accorded to the people of J&K through Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which had been placed in recognition of the contestation of citizenship in the region. Such a move was undertaken in absence of a democratically elected local government during the (Indian) President’s Rule, bifurcating IAJK into two Union Territories of J&K, and Ladakh. Such a measure by the Indian government was to further its ethno-nationalist imagination of Akhand Bharat, to extend the idea of a Hindu Rashtra to the region by initiating a demographic change by changing the domicile law – which until now restricted non-natives from purchasing land and availing government jobs in the region. This move of disenfranchising the native populace, the subjugation of their democratic rights, and enforcement of a de facto economic blockade lead to political upheaval, against which the Indian state placed in force Section 144 (CrPC). Such a law enforced a moratorium on the normal functioning of the society by limiting the physical movement of all individuals, even as a communication blockade was initiated. Incidentally, the BJP continues to claim that their move of changing the federal relation with IAJK would benefit the nomadic tribes of the region by extending them the hitherto unavailable political reservation and extension of Forest Rights Act (2006).

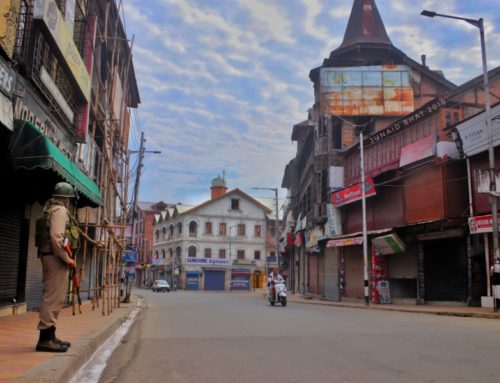

While the Indian state representatives keep making loud claims of benevolence towards the tribal population, the amalgamation of political shut down along with the pandemic lockdown for colonial considerations has brought nothing but misery to the Bakarwal nomads who had migrated and settled in the plains of Jammu during the winter. The shutdown immediately after the amendment to Article 370 of the Constitution of India, caught the Bakarwal community unawares and off-guard. Owing to the economic blockade and closure of markets, the nomadic community could not trade with the local meat and wool merchants. The nomads usually supplement their livelihood by engaging in unskilled work in the construction sector and by accessing employment schemes such as the MGNREGS. However, due to suspension of such public and private activities, the members remained out of work for the duration of the winter, while their subsistence costs drastically increased due to the logistical jam in the Public (Food) Delivery System which could have been used to access food grains at a subsidized rate. Furthermore, with the closure of educational institutions and suspension of policies such as Mobile Schools, the tribal children continued to be denied an education. All this while, the provincial administration failed to implement the now extended Forest Rights Act in the region, making the community vulnerable to evictions and denial of access to pastures in forest reserves in the Jammu region – limiting food sources for their flock. The shortage of food for the herd was exacerbated with no access to veterinary medicines and fodder from the Animal Husbandry department in the region. The increase of sectarianism in the region post-amendment led to increased calls of eviction of the Bakarwal communities practicing Islam by Hindu nationalists of Jammu from the rented vacant plots that they inhabit in the region – leading to land conflicts, increase in rent, along with economic ostracisation of the community where the local populace refused to purchase dairy products from the Bakarwals, affecting their livelihoods.

Already battling the vagaries of the political shutdown, the COVID-19 pandemic has acted as the last straw on the camel’s back. Due to the imposition of nationwide lockdown measures to curb the spread of the virus, the Bakarwal community’s migration schedule has been massively disrupted. Even as the Central and State governments of India set up policies such as Vande Bharat, to aid the return of white-collar workers who had emigrated to foreign countries and across the nation during the lockdown, no such initiative was launched for this nomadic community.

Almost 800,000 nomads got stuck in cramped rented plots in Jammu till late April of this year, a full month’s delay in setting out for the higher reaches.9Hassan, F (4 May 2020). ‘In Jammu and Kashmir, inconsistent lockdown rules have disrupted seasonal livestock migration.’ Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/960770/in-jammu-and-kashmir-inconsistent-lockdown-rules-have-disrupted-seasonal-livestock-migration During this period, the provincial government failed to provide any substantial aid to the tribe in the form of rations, medical assistance, rent relief, and fodder for the livestock.10Ahmad, M (21 June 2020). ‘Trouble Mounts for J&K’s Nomads During Annual Migration to Greener Pastures.’ The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/agriculture/jammu-nomads-bakarwal-annual-migration-animal-rearing The increased cost of living, fall in income, and delay in transhumance shall bear a cascading effect on the livelihood and the lives of the nomadic community. The health and numbers of the flock, which cannot bear the summer temperatures in the plains, significantly deteriorated and shall continue to plummet as the delay in reaching the pastures shall reduce the availability of good grass in the high-altitude pastures. It was only by April 23 that the provincial government of IAJK allowed Bakarwals to travel as a complete dera or household – including the young and the elderly. However, the road back to the summer abode remains fraught with obstacles for the tribe. The provincial government sat on its haunches in issuing Mattoos or written permits required by the community for passage to their forest lands, claiming lack of stationary pads. Moreover, as stated by the J&K Advisory Board for Development of Gujjars and Bakarwals, the administration has refused11Iyer, A (17 April 2020). ‘Worried & Confused’: 15 Lakh Bakarwals Begin Migrating to Kashmir. The Quint. Retrieved from https://www.thequint.com/news/india/jammu-and-kashmir-gujjar-bakarwals-worried-confused-migrate-lockdown to issue Mattoos for milch animals viz. cows and buffalos, this being in accordance with the sectarian aims of transferring ownership of such animals away from the Muslim community. With each milch animal costing as much as INR 40,000, the Bakarwal community is set for a huge financial setback.

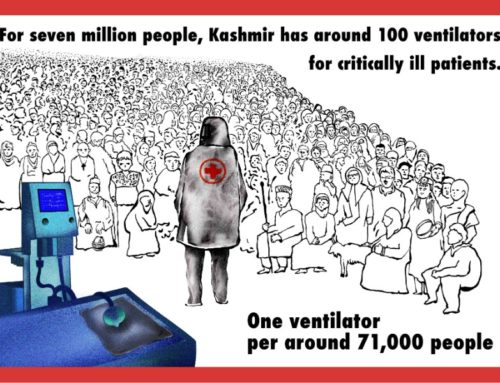

As the Bakarwals set out to migrate along their ancestral routes, often through COVID-hit zones, the administration failed to set up health facilities for the tribes folk and their livestock- both vulnerable to diseases and injury during the migration. The administration has also refused to allow the use of vehicles, which would have speeded up the movement of large animals and safeguarded vulnerable members of the community. The road to the higher reaches continues to be treacherous as the state administration has not engaged in the upkeep and clearance of snows from the route that the community used to migrate into regions as far as the Zanskar range in Ladakh.

COVID Colonialism and the Future of Traditional Livelihood of the Bakkarwal Tribe

The distress and marginalization of the Bakarwal community are set to exacerbate owing to the unilateral promulgation and implementation of colonial policies by the BJP-led Indian government even as the COVID-19 Pandemic besieged the region. Using the pandemic as a state of exception the Indian state waylaid democratic processes and suppressed dissent to further their ethno-nationalist agenda in IAJK, which in the long run shall affect the traditional mode of social reproduction within the Bakarwal tribe.

After the implementation of Constitutional Orders numbered 272 and 273, the Indian state took away the autonomy of the natives of IAJK, including the tribes, by stripping them of the solely existing indigenously formulated Constitution in the Indian Union along with their land and statehood. This led to a political disenfranchisement through the dissolution of the Legislative Assembly and replacement of one with a reduced number of political representatives, bound to the Indian Parliament via a Lieutenant Governor. Unsurprisingly, the absence of any elected representatives and the presence of an administrative puppet of the Indian Union led to the implementation of anti-native policies that aimed to propagate colonial extraction within the region. Using the pandemic to enforce limitations on popular expression, the provincial government notified new Domicile Rules in the region.12Ganai, N (1 April 2020). ‘Amid Coronavirus Lockdown, Govt Comes Up With Domicile Law For Jammu And Kashmir.’ Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-govt-comes-up-with-domicile-law-for-jammu-and-kashmir/349830 These rules regulate ownership of immovable private property and employment, opening up greater contestation over local resources from non-natives who had emigrated to the IAJK for employment but did not hold the status of permanent residents as per previous rules. As a means to actuate a demographic change in the region, the new regulations shall primarily allow members and families of Indian civil servants and the Indian military to compete for a greater share of local resources through political bargaining.13Bég, M (30 May 2020). ‘J&K’s New Domicile Order: Disenfranchising Kashmiris, One Step at a Time.’ The Wire. Retrieved rom https://thewire.in/rights/kashmir-domicile-law Even though the BJP claims to set up political reservation14Bhat, S (18 August 2019). ‘BJP to woo Gujjars, Bakerwals.’ Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/bjp-woo-gujjars-bakerwals-1581881-2019-08-18 of the tribes of IAJK, since, the Bakarwals barely access state institutions, own private property, and hold documents issued by the modern state, they shall remain undocumented and underrepresented. In their place, the creamy layer within the Indian tribal groups, a part of the colonial machinery in IAJK, shall usurp the benefits supposedly extended to the nomadic tribes of the region.

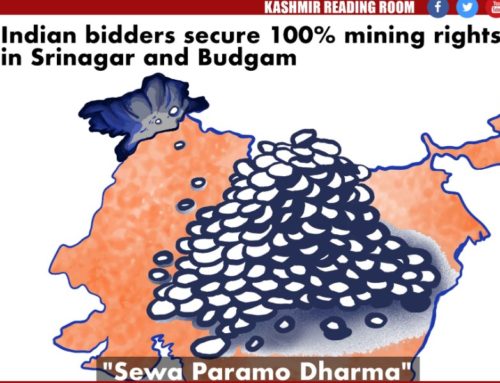

The commensurate material marginalization through increased obstacles to transhumance mode of livelihood within the community is apparent. The extractive colonial policies of the Indian state have opened up the natural resources of J&K to Indian subjects and private corporations, allowing them to participate and establish exploitative hegemonies in the local economy. The traditional pastures, essential to the livelihood of the Bakarwal communities are at high risk of being subjected to mining activities, with already over 500 mineral blocks being auctioned – a sizable number in areas with a high tribal population such as Anantnag and Kulgam. In the absence of implementation of the Forest Rights Act, alongside the re-organization of the J&K Forest Corporation15The Kashmir Monitor (25 June 2020). ‘Govt creates J&K Forests Dev Corp, company to take over erstwhile SFC.’ The Kashmir Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.thekashmirmonitor.net/govt-creates-jk-forests-dev-corp-company-to-take-over-erstwhile-sfc/ as a for-profit company, and the notification of draft Environment Impact Assessment 2020 – which has diluted environmental safeguards16Mohanty, A (6 July 2020). ‘Why draft EIA 2020 needs a revaluation.’ Down To Earth. Retrieved from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/environment/why-draft-eia-2020-needs-a-revaluation-72148 – it is quite clear that the Indian state is setting up local land, water, forest and mineral resources17Javaid, A (6 February 2020). ‘Outside firms enter the mining race in J&K, lease earnings touch crores from lakhs.’ The Print. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/india/outside-firms-enter-mining-race-in-jk-lease-earnings-touch-crores-from-lakhs/360175/ up for capitalist exploitation by large MNCs, with no heed for the indigenous tribes dependent on the same for their survival. Similarly, the tourism industry that the Bakarwals have used to supplant their livelihoods is set to be taken over by large private groups which shall potentially purchase large swathes of lands and gentrify the region, excluding the nomads from providing services to tourists in the vicinity of their projects.

One can foresee an imminent expansion of private ownership and militarisation of lands, that the Bakarwals have traditionally traversed as a community, leading to further shrinkage of spaces where the nomads have dwelled and secured their livelihood. With the dilution of domicile laws18Kissu, S (27 June 2020). ‘Jammu Feels Betrayed, Kashmir in Panic After Domicile Certificates Issued’. NewsClick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/ammu-kashmir-felt-betrayed-kashmir-panic-domicile-certificates-issued , there shall be an expansion of the real estate sector for private settlements and industry in the region, mostly accessible to non-natives with disposable incomes and access to credit institutions. This could raise the cost of living and create private boundaries and borders, impeding the traditional migratory paths of the nomadic tribes, as with the establishment of Ladakh as a separate administrative territory. Furthermore, the Bakarwals are besieged with increased political turmoil, resurgent armed rebellion, and escalation of Sino-India conflict over claims of territoriality in the Galwan Valley, affecting a greater militarization in the region by the Indian forces, which seek out and occupy large swathes of grazing grounds for their bases. The militaristic occupation of tribal lands is worsened by impunity accorded to the Indian Armed forces via AFSPA19The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958, wherein they escape civil accountability for inflicting material damage on the community, such as running over their flock with their vehicles, as seen during the nomadic migration of the Bakarwals in the past.

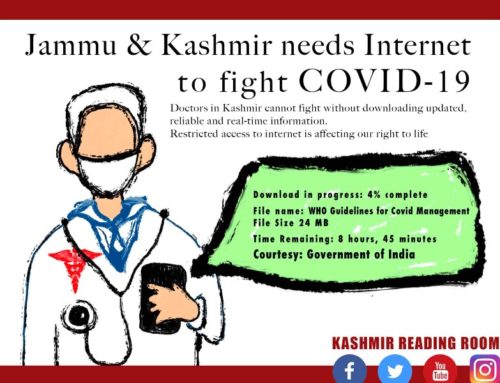

The insidious nature of the colonial state also impedes the shift of traditional mode of production within the Bakarwal tribe on to the mainstream modes of livelihood which are highly skilled and require formal school education. The shutdown of public and private schools in conjunction with denial of 4G internet in IAJK since, August 5 last year; in addition to the state-backed shift to online modes of education during the pandemic, completely place the members of Bakarwal tribe at a disadvantage, who have historically been dependent on mobile schools for imparting traditional knowledge and culture to their children. This educational marginalization can be foreseen through the fact that 86% of children in the region cannot access online learning which is being valourized by the current Public Education Department. As private educational institutions are set to increase in the region, ‘technocratic inegalitarianism’ while imparting education will only rise and further marginalize future generations of Bakarwals, and limit their inclusion in formal work economy; one only set for increased competition with the opening of access to the non-natives.

Given all the ‘developments’ in the IAJK, the Bakarwals are doomed to part with their traditional work practices and exist as undocumented workers ripe for exploitation by the Indian private and public sector, with limited recourse to state institutions for representation and justice. The tribes face an almost insurmountable challenge of standing up to the sectarian colonial state for securing their social, economic, and political rights.

About the Author: Afreen G. Faridi is a Ph.D. Candidate at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His research seeks to locate the interstices of constitutionalism and conflict for determining their impact on work practices in Kashmir. His writings include poetry on conflict, trauma and memory.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.