Remembering Afzal

Amrit Wilson

It was a cold grey winter day in December 2007 when I got permission to visit Afzal Guru in Tihar jail. I had so many questions I wanted to ask him, so much I wanted to hear. In the event it was the briefest of meetings. He was only allowed a few minutes outside the cage-like structure in Jail no 3 of the high-security wing where he was being held, and we could only speak separated by a security barrier. I remember mainly the warmth of his smile and the friendship he extended to me. He told me he had received my letter and thanked me for the events demanding his release which South Asia Solidarity Group had organised in London – a demonstration in front of the Indian High Commission, a letter signed among others by 4 Labour MPs, a public meeting, an Early Day Motion in the British Parliament and the successful lobbying of Members of the European Parliament to take his case up with President Abdul Kalam during his upcoming visit to Strasbourg.

The previous November, Afzal had filed a petition to the President of India under Article 72 of the Indian Constitution asking for clemency. It was more like the statement of a political prisoner asserting their legal right to justice than a plea for mercy.

“When a man faces certain death things become clearer,” he had written “I find myself wondering if my death can achieve any kind of justice or bring us closer to peace. I really do not think [ so] … I would like to write and tell you my story, as I see it, in the hope that you will spare my life but also that you will understand the stories of thousands of other Kashmiri youths who are locked inside jails. I want you to understand why the Kashmiri people have taken to the streets on my behalf. Their anger, their anguish, their pain is still not understood in India.” He had gone on to recount what it was like for his generation of youth who had grown up during the 90s, why he had joined the movement, why he had surrendered and what life was like for surrendered militants. “In those heady days, [in the mid-90s] I was like thousands of youths, who left the comfort of our homes, the security of our future jobs and gave up our dreams, joined the movement and went over to Pakistan.” After only 3 months, during which he did not receive any training he, like many others, had returned to the valley and surrendered, ‘disillusioned by the fact that both India and Pakistan were using Kashmiri youth as their pawns’.

But life as a surrendered militant meant facing a constant reign of terror. “The officers of the Indian army and the STF would not allow me to live a normal life. They would call me and other surrendered militants to their camp, beat us, torture us and humiliate us till we agreed to become informers [or work for them in other ways]”

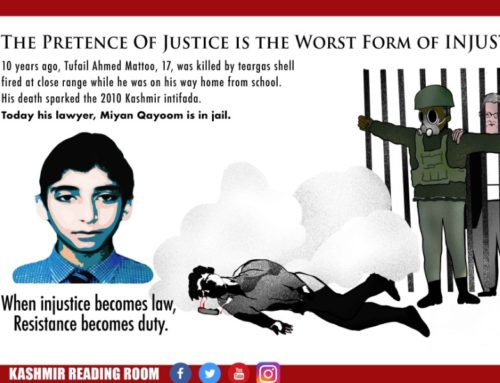

He went on to relate the stark and dehumanising injustice he had faced at every step from arrest to incarceration in Tihar. Before the case went to court, he had faced a trial by media organised by officers of the Delhi police cell. His ‘confession’, obtained as he sat in handcuffs with his torturers standing around him had been broadcast over and over again for two days by NDTV accompanied by remarks such as ‘See how natural, how truthful, how fluent his statement appears’ and ‘Who can believe that such a statement can be given under torture’. Viewers were encouraged to act as a virtual lynch mob by soliciting SMS messages from them asking whether he should be hanged in light of the ‘confession’ being broadcast. At the trial itself he had not been represented by a lawyer. He was from a poor family and could not afford lawyers’ fees and every lawyer he had requested had refused to act on his behalf.

The campaigns across the world, interventions at the British and European Parliament and the expressions of outrage by a wide variety of people and organisations in Kashmir were, of course, in the end, unsuccessful. In the early hours of February 9, 2013, Afzal was hanged in secret and buried in Tihar jail. His family were not informed and a memo to his wife with Afzal’s name insultingly misspelt arrived only after he had been executed.

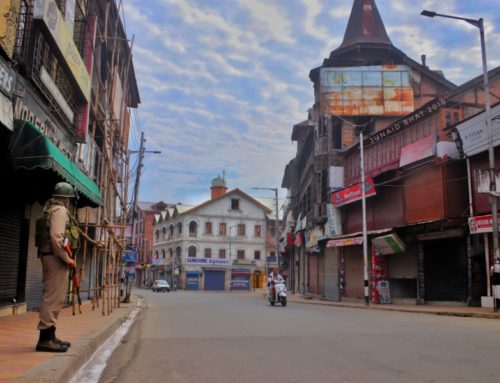

The news was received with an unstoppable outpouring of grief and anger in Kashmir. People poured out onto the streets despite a curfew being imposed. They were met with further repression. In India, at the time, and even more so as the years passed and the BJP came to power, every attempt was made to stop any discussion of the terrible injustice Afzal Guru had faced. He was seen as dangerous even in death – so dangerous that organisers of meetings about him were openly threatened by the BJP’s foot soldiers. At the same time his body, like that of Maqbool Bhat before him, has not been returned to Kashmir and to his family.

In the last month, however, with the arrest of DSP Davinder Singh in Jammu & Kashmir, allegedly for ferrying Hizbul Mujahideen militants to Delhi, Afzal Guru’s name is in the news again. The Indian media, who in general had shown little interest in his testimony, while he was alive are finally unearthing the letters he had written to his lawyer Sushil Kumar and to human rights organisations. In these documents he had described his entrapment by the STF, the tortures, relentless extortion and threats to lives of his loved ones which he had faced from this very Davinder Singh and other police officers and most significantly he had stated that it was Davinder Singh who had introduced him to a man known as Mohammed and ordered him to do the ‘small job’ of taking him to Delhi and finding him a rented place to live. Mohammed, who was clearly not a Kashmiri, was later identified as one of the five terrorists who stormed the Parliament building on December 13, 2001, who had all been conveniently gunned down by the police so no further investigation was possible.

Questions are being asked about why these documents with their incriminating evidence were not discussed in court. So far, neither the judiciary nor politicians have provided any answers. Other older questions continue to hang in the air, also unanswered: Why did the Supreme Court admit there was no direct evidence against Afzal Guru and then sentence him to death? Why did it rule that by killing an innocent man ‘the collective conscience of the society will be satisfied’, what did that say about Indian ‘society’? And why, even before the BJP came to power were Indian institutions so eager to appease the violent Hindutva forces who wanted Afzal killed, when clearly, as Nandita Haksar wrote, back in 2006, his hanging institutionalised the growing lawlessness of the police and authoritarianism of the Indian state and gave a fillip to the growth of Hindu fascist forces.

Today, in India, with the judiciary often acting like a mere appendage of the ruling party, it is unlikely that these questions will be answered. To honour Afzal Guru’s memory, however, we must continue to ask them and demand justice for him while we also campaign for his body to be returned to Kashmir and his family.

References:

- (26 January 2007). ‘Torture, Lies And A Fabricated Confession: No Death Penalty For Afzal Guru’ Islamic Human Rights Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ihrc.org.uk/activities/events/5720-torture-lies-and-a-fabricated-confession-no-death-penalty-for-afzal-guru/

- Haksar, N (5 October 2006). ’Afzal’s Story’. Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/afzals-story/232712

About the Author: Amrit Wilson is a writer and activist on issues of race and gender in Britain and South Asian politics. She is a member of the South Asia Solidarity Group collective. She was a founder member of Awaz, the first South Asian women’s activist organisation in Britain. Her books include Finding a Voice, Asian women in Britain which won the Martin Luther King award for 1978 and has been republished with a new introduction and other additions (Daraja Press 2018) and Dreams, Questions, Struggles –South Asian Women in Britain (Pluto Press 2006).

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.