Mental Health and Kashmir:

A Longitudinal Perspective

Dr. Amit Sen

Atifa1Name changed for purpose of privacy and security of the individual was 14 when I first saw her. She was bright and acutely perceptive and was scrutinizing me from head to toe. It took her a while to open, and once she did there was no stopping her. She was articulate and vivid in her descriptions, especially with her experiences on the streets of Shopian, a town in South Kashmir where she was growing up. Considered to be very intelligent in school and amongst her family, she was expected to break away from the mould and do great things, like becoming a doctor, which was her dream. She was the class topper till grade 8 and was also known for her talent in Art, but things changed once she came to grade 9. Atifa started having fainting attacks in school, at home, and even when she was walking the streets of Shopian at times. She was rushed to the district hospital for the first few times, who referred her to the Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences in Srinagar. A range of investigations didn’t reveal any medical condition, and therefore, she was referred to a psychiatrist. One of my colleagues in Srinagar directed the family to consult me in Delhi 3 years ago, as there was no child psychiatrist in Kashmir those days, although many things have changed since then (Srinagar now has a dedicated child and adolescent mental health service with trained professionals responding to consequences of the series of socio-political and medical crises in innovative ways). Atifa came to see me from time to time for the next 2 years, and as I got to know her better, a complex picture of what young people in Kashmir were going through started unfolding before me. Atifa had got caught, on a few occasions during her journey to school or back, in the crossfire between local boys pelting stones and security forces firing from automatic weapons, and had seen young people from her community bleeding and writhing in pain after being hit by pellets. Some of them would end up losing their vision or get maimed for life. Few of the older youth would try to persuade her to join them in their reprisal against the state, and that would tear her apart, given her ambition of becoming a doctor/healer in her community. She started getting vivid dreams and flashbacks of disturbing memories that kept her awake at night. There were mood swings, severe anger outbursts towards her family and friends, and she found it increasingly difficult to focus on studies. Her academic grades were slipping, and she started missing school, which used to be her favorite place, often. She would be overwhelmed with intrusive and distressing negative thoughts and even thoughts of self-harm and suicide. Atifa was clearly suffering from the consequences of traumatic experiences and was diagnosed with depression, dissociative disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. We met sporadically, as and when her family could get her to Delhi for treatment but lost touch once the political shutdown was imposed in August 2019.

My relationship with Kashmir has been long and intimate. The first time I visited was when I was 14 years old, with my family in the summer of 1974, expecting to experience paradise, as you do when you are told about Kashmir, especially in the romantic teenage years. The trip was far from perfect, but I remember being struck by the sheer magnificence of the Lidder Valley in Pahalgam where we had camped for a couple of days or the magic of the serene waters of Dal Lake reflecting the hills and the majestic gardens arching around it. I was also intrigued by the people who were so different and earnest, and the food blew my mind (and taste-buds). I was not concerned about mental health, of my own or anyone else’s those days, but these rich experiences left a mark deep enough to make myself a promise that I will return one day for a longer period.

So, I did not lose the first opportunity I got to work there, as soon as I completed medical school. In January 1983 Badami Bagh Cantt, where I lived next to the hospital I worked in, was cold and detached from the rest of Srinagar. Not because of the heavily armed and fortified walls that we see today, but due to the distance and scanty transport during winter months. Yet, I would take a public bus or hitchhike my way into town quite frequently after work. Interacting with local shopkeepers and people at snack bars, gorging on street food in and around Lal Chowk, walking along the canals leading up to Dal Lake, watching children play as the colours of spring cut through the grey winter, my intrigue and wonder about the valley and its culture kept growing. Although I was not trained in mental health back then, my natural curiosity and observations about people gave me a good understanding of life in the Valley. They were generous and hospitable people who were proud of the distinct identity that they believed was separate from the rest of India. As an outsider, I was made to feel welcome and included, even in their passionate and often charged discussions about politics in the region, which has always been fraught and complicated even in the best of times. But those were pre-insurgency days and there was a basic level of trust and openness amongst people and towards each other. And the children were everywhere, running and prancing over the steps of Nishat Bagh, going to school in Shikaras, picnicking by the rapids in Pahalgam and snowboarding – on makeshift wooden boards – down the winter slopes of Gulmarg. There was spring in the air for most of the year.

The next time I visited Kashmir was in 2003, in the role of a child mental health professional, as part of a team that was given to address the needs of traumatized children and fractured families in the valley. This time, the picture-perfect landscape had been punctured by protruding nozzles of automatic guns from camouflaged security bunkers at close intervals throughout the city of Srinagar. Over the next 3 years, through multiple visits, we met dozens of children and adolescents, many of them orphans and others from families that were damaged and disintegrated due to insurgency, terrorism, and excesses from security forces. Some 8-year-olds had lost the ability to play spontaneously, and instead, would sing songs of martyrdom where they proudly proclaimed that the only objective in life was to march to their death in the quest for freedom. Teenagers and the youth, initially mistrusting and reticent, would break down and pour their hearts out once they got to know us better. There were accounts of children and families getting caught in the crossfire between terrorists and security forces, fathers and brothers being picked up by men in uniform never to return, and young men getting ruthlessly murdered in front of their kin. We met parents who appeared jaded and burdened by the looming threat, uncertainty, and inability to ensure safety for their children and families.

Such repetitive and violent trauma in endemic war zones can be deeply damaging for the community, especially children and adolescents who could be scarred for life and pass on their fear and anger to generations that follow. The impact of such trauma could be wide and complicated. It could range from stunted growth and severe behaviour disorders in young children, substance misuse and self-harm behaviours during the teenage years, to depression and anxiety disorders in late adolescence. Others develop a range of physical symptoms that are disabling and warrant repeated visits to the doctors. And some turn their anger into hatred and violence towards others, including family and their community at times, or towards people they see as their oppressors or adversaries. They don’t need to be tutored or indoctrinated to form extreme attitudes and prejudices. They learn from the brutal life lessons that surround them – that repeatedly break their trust in people whom they expected would care for them and protect them.

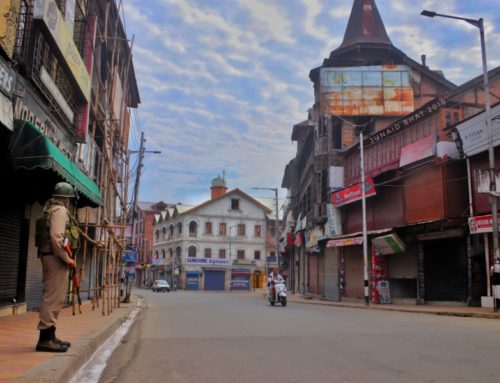

The last time that I went to Kashmir was the end of September 2019, with a fact-finding team2‘Imprisoned Resistance: 5th August and its aftermath’ (October 2019) http://www.pucl.org/sites/default/files/reports/Imprisoned%20Resistance-final%20for%20dissemination.pdf that wanted to take a close look at the ground realities after the shocking shutdown of Kashmir on the 5th August 2019. This time there were no children on the streets or the gardens; in fact, they were not even in schools. The streets of Srinagar were completely deserted, and it felt like a ghost town in the center of the city (Lal Chowk) on a Sunday afternoon when I landed there.

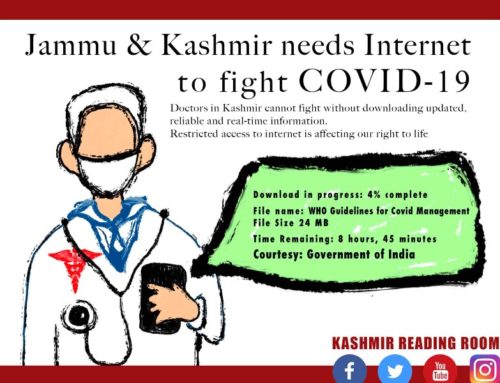

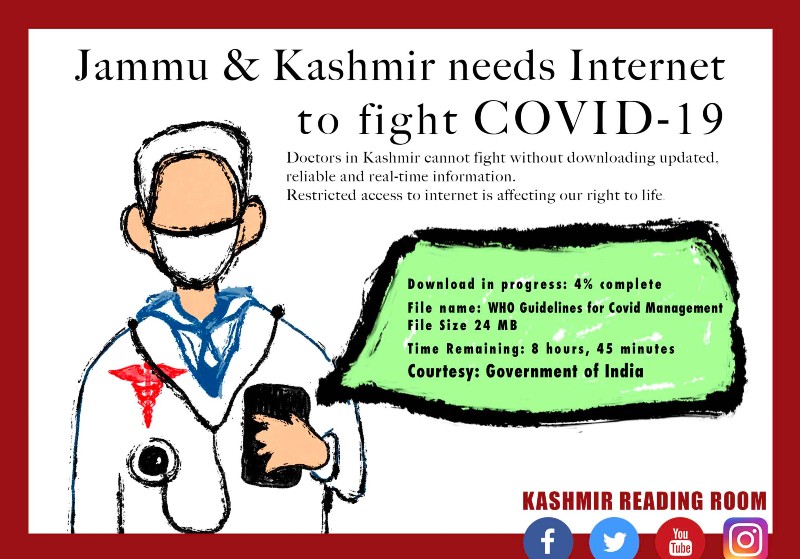

Mental Health (MH) services and their functioning had been badly hit. The footfall of children and families at the newly formed Child Mental Health Center in Srinagar, of both new registrations and follow up cases, saw a sharp decline in the month of August after the shutdown. The numbers were picking up slowly when I visited them but were nowhere near the footfall in June/July. It was believed that the lack of transport, communication, and lack of trust in government agencies might have contributed to this decline. Attempts by MH professionals to reach out to the community was met with extreme hostility from local youth at first, but they had found innovative ways of collaborating with community leaders and workers to provide Psychological First Aid (PFA) to children from smaller towns and villages. The clampdown on all forms of communication had hugely hampered the exchange of notes and important data between the different MH centers and organisations in the state, which is essential for good practices of mental health.

The children and adolescents coming for PFA in Pulwama and Kulgam, the only two districts the mental health teams could reach out to at that time, were reporting extreme violence at the hands of security forces, which had created an atmosphere of terror and panic amongst young people and their families. They were sharing experiences of paralysing fear, acute anxiety, panic attacks, depressive and dissociative symptoms, post-traumatic symptoms, suicidal tendencies, and severe anger outbursts. Grassroot workers were unable to refer children showing clear signs of trauma and abuse, to more centralised facilities that are better equipped to deal with such complex cases, due to the lack of transport and connectivity. There was a marked increase in psychological distress in 70% (as estimated through a survey at that time) of the population, although how that would translate into mental health disorders was yet to be seen.

After long months of oppression and shutdown, the Valley opened to a semblance of normalcy with the advent of spring this year. Schools reopened after 8 months at the beginning of March, only to be shut down again in 3 weeks, this time due to the COVID-19 lockdown. “The anxiety surrounding political uncertainty has given way to fear of life; Kashmiris have to deal with both now”, lamented one worried MH professional in Srinagar. Fortunately, the 2G internet and social media services were started sometime in March 2020, the impact of which on children has been mixed according to my trusted colleagues working in Kashmir. While many have taken to online classes and learning with enthusiasm, there are many others whose routines are completely disrupted as they can’t let go of screens till late night/early morning hours. There are complaints from parents of behaviour problems in the form of disobedience, rudeness, mood swings, and aggressive outbursts. Some of them are showing clear signs of screen addiction. Given the fear of contacting COVID and the reluctance of families to venture out, MH professionals are finding innovative ways of working with children and families, most often through online services.

The footfall of adult patients, on the other hand, has been increasing steadily since winter months and has hit its peak now; the numbers attending the psychiatric outpatients at the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (IMHANS), Srinagar are seeing record highs. However, for every person coming to seek help, there may be multiple others who choose not to avail of government services due to the massive breakdown of trust between the common man and the State. We are, perhaps, nowhere near knowing the real numbers of people in acute psychological distress or those with a full-blown mental health disorder. Professionals working on the ground believe that the aftermath of this imbroglio and the trauma suffered by thousands of people will become evident in the months and years to come.

What is evident is that it will require revolutionary vision, deep compassion, and humongous resources to begin to address the suffering, mental health needs, and healing of the Kashmiri people. I sincerely hope that all stakeholders are willing to put their differences aside and can pull together to respond to this glaring need.

About the Author: Dr Amit Sen completed his MD in Psychiatry from NIMHANS, Bangalore and trained in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the UK. He has worked with national (Haq, CSJ, The Foundation) and international organizations like UN Human Rights Commission and UNICEF in the area of Trauma, child sexual abuse and juvenile justice. Dr Sen is the co-founder & director of Children First, a multidisciplinary institute that provides clinical & community-based services, training and research in child and adolescent mental health. He was part of an eleven-member team that visited Kashmir in September 2019.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.