Kashmiri Sikhs after Abrogation

Khushdeep Kaur

Elected to power by an overwhelming majority in its second term, the Hindu nationalist BJP government in a bid to ‘end militancy and develop Kashmir’, on August 5, 2019, de-operationalised Article 370, the legal instrument defining Kashmir’s relationship to India ‘lock, stock and barrel’, and took away Kashmir’s statehood by breaking the state into two parts and demoting erstwhile State of J&K to a Union Territory. The only Muslim majority state in India’s constitutionally secular polity, Kashmir had its own Constitution and could govern its own affairs, by decree of Article 370, which outlined the terms under which Kashmir acceded to India after the end of British colonial rule.

Rendering the state subjecthood that formed the very basis of Kashmiri being worthless, the government’s move, fundamentally altering the relationship between India and Kashmir, is being hailed both in the corridors of power and on the streets as the realization of an unfinished project of integration. Post-colonial India, according to the BJP (the ruling party of India) is now a completed project, with ‘One Nation One Constitution’. The two greatest changes that this move will usher in are, the opening of the possession of land and jobs to non-Kashmiris, both of which were restricted under Article 35-A of the Constitution of India.

It is not surprising that the brutal lockdown and erosion of Kashmiris’ fundamental freedom has been hailed by the Hindu right as a ‘recapture of the Valley from Islamists’ and celebrated by millions of Indians. The mainstream discourses on Kashmir have viewed the Kashmir conflict through a largely reductive lens of communalism: to the average Indian, it is a conflict between Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. This narrative, reinforced when the heightened militancy in the 1990s led to the mass exodus of Kashmir’s Hindu Pandit community (discussed below), conveniently ignores the experiences of those minorities (including Pandit families) who continue to live in Kashmir and bear witness to all of its trials and tribulations.

In 2018, I began my Ph.D. research with one such community, the Kashmiri Sikhs, a micro-minority community (a term they use to describe themselves), that constitutes less than 2% of the population of Jammu and Kashmir as per the 2011 Indian Census. Rendered invisible in this conflict, my research aims to afford the Kashmiri Sikh community the visibility that is their due while simultaneously nuancing our understanding of the multiple lived realities of Kashmiris beyond the Hindu-Muslim communal binary. Over the course of 10 months of ethnographic fieldwork, I conducted 70 formal interviews with Kashmiri Sikhs and 30 with Kashmiri Muslims, in addition to hundreds of hours of observation and informal conversations. In this brief, I present a historical and contemporary overview of the Kashmiri Sikh experience, drawing on my research material, before discussing the implications of abrogation vis-à-vis this community.

The Kashmiri Sikhs: A Brief History

Having lived in Kashmir for generations, the Kashmiri Sikhs trace their lineage to the extensive and well-documented travels of the first Sikh guru (preacher), Guru Nanak, across Kashmir. Sikhism advancement in Kashmir is also attributed to the travels of the sixth Sikh guru, Guru Hargobind. Each asthan (place) to which the gurus traveled is marked by gurudwaras that are the living testament of this history. Besides this, there is a second lineage which is traced to the rule of two Sikh rulers, Sukhjiwan Mal (1753-63) and Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), under whose rule Sikh soldiers from the Punjab region were brought to Kashmir to serve allotted land and settled in Kashmir.

In 1947, as India and Pakistan were reeling from the horrors of the brutal Partition after their newly attained independence, the Kashmiri Sikhs fought tribal ‘invaders’ in what has become known in popular parlance as the ‘Kabali raid’. Over 30,000 Sikhs, by the community’s estimates, were killed in this barbaric violence that took place primarily in the Baramulla area in North Kashmir. There is even a Partition memorial that remains the sole marker of this violence, located in the beautiful village of Chandoosa (about 16 km from Baramulla).

At present, an estimated 60-80,000 Sikhs reside in Kashmir Valley. While the bulk lived in rural areas spread out across Kashmir, the militancy triggered a migration to urban areas, mainly Baramulla city and Srinagar. Many families, however, still live in villages or if they have migrated, still retain property and lands in their ancestral villages. Historically agriculturists, Kashmiri Sikhs also work in government services, own private businesses and are recruited in the police and military.

The Chittisinghpora Massacre

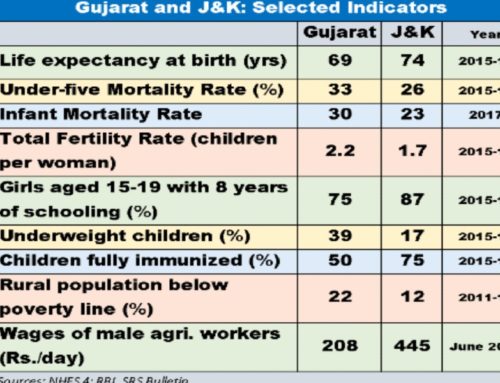

A multi-religious and multi-ethnic region, Indian-administered Kashmir is demographically predominantly Muslim (96.4%), with the two other distinct religious groups in the Valley being Sikhs (1.8%) and Hindus (2.4%). A significant proportion of Kashmir’s Hindus are the Kashmiri Pandits. When Kashmir’s militancy – now in its fourth decade and which author Gowhar Geelani has characterized as largely symbolic – was at its height in 1989-90, militant outfits like the Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) issued public threats to the Valley’s minorities, informing them that their only choices were to ‘Ralive, Tsaliv ya Galive’ (either assimilate, run away or perish), and orchestrated the killings of influential members of the Pandit community. Already feeling alienated by state-led policies which they believed favored the majority Muslim community, such as land reforms and political delimitation, the killings were the last straw for many, leading to the exodus of an estimated 170,000-300,000 Kashmiri Pandits.

As Kashmir stood recovering, from what many consider the most shameful event in its history, a mere decade later, the Sikh community, never before the target of violence, suddenly found itself under attack in Chittisinghpora village, located in South Kashmir’s Anantnag district (about 70 km south of the capital, Srinagar).

Chittisinghpora is the largest of the 14 Sikh villages in South Kashmir, hidden away in the bosom of the Pir Panjal mountains. It is settled by nearly 400 Sikh and 80-100 Muslim families which live in close geographic proximity and are connected by strong economic but somewhat sparse social ties. On March 20, 2000, at around 7:45 in the evening, unknown men wearing army overalls made their way into the village, lined up 36 men on the pretext of conducting a routine ‘crackdown’ (search and seizure for militants) – eighteen in front of each of the two main gurudwaras in the village – and gunned them down moments later. Only 60-year old Nanak Singh, who lay in the pile of dead bodies left behind by the killers, survived.

The attack came as a shock to Kashmiris; for as long as anyone could remember, both Sikhs and Muslims had lived together peacefully. While no one knows who perpetrated the massacre, almost everyone – Sikh or Muslim – believes that this was the handiwork of ‘agencies’of the Indian state. The popular narrative is that the attack was carried out to project to the then President of the United States, Bill Clonton, who was visiting India on that very day that there existed a problem of ‘Islamic Terrorism’ in Kashmir and that Kashmir’s minorities were unsafe.

The attack came as a shock to Kashmiris; for as long as anyone could remember, both Sikhs and Muslims had lived together peacefully. While no one knows who perpetrated the massacre, almost everyone – Sikh or Muslim – believes that this was the handiwork of ‘agencies’ of the Indian state. It is suspected that sinceThe popular narrative is that the attack was carried out to project to the , the then President of Americathe United States, Bill Clinton, who was visiting India on that very day, the Indian state intended to project that there existed an ‘Islamic extremism’ problem in Kashmir – a Muslim-majority region in the Indian Union – and that Kashmir’s minorities were unsafe.

Fearful that the massacre would trigger another minority exodus, prominent political leaders such as Shabeer Shah of the National Conference (NC) party of Kashmir, visited the community in Chittsinghpora upon being informed that Sikhs were contemplating leaving the Valley. Shah, as survivor Nanak Singh (real name) recalls, remarked, “aap hamari laashon se jayenge” (you will leave over our dead bodies). Sikh leadership from the neighboring state of Punjab too visited the village immediately afterward, and after deliberating with them about whether they should leave, the Sikh community ultimately ended up staying, with only three out of the 400 households in Chittisinghpora migrating elsewhere.

Over the years, the Chittisinghpora case all but disappeared from public memory, only kept alive by the local commemoration that is held every year in the village. Although twenty years have passed, justice remains a far-fetched goal for the families of those killed in Chittisinghpora. Frustrated by the lack of any impartial inquiry and a series of court cases that appear to go nowhere, Nanak Singh remarked to me, “No one can do anything. The militants will say the government did it, the government will say the militants did it. We are scapegoats”. He followed up the statement by saying that at this time, the Kashmiri Sikh is helpless. “Whenever they need us, they will sacrifice us”, he said, implying that for either side, Sikhs are disposable pawns in this ongoing battle.

Rebuilding Trust

While militancy has triggered a slow migration to urban areas in the capital Srinagar and the highly urbanized Baramulla city in the north, the bulk of the Sikh population in south Kashmir still lives in rural areas in Anantnag and Pulwama districts. Several Kashmiris whom I interviewed – both Sikh and Muslim – repeatedly alleged that the intention behind targeting the micro-minority Sikh community was to create a Sikh-Muslim communal divide and similarly trigger a mass displacement of Kashmiri Sikhs.

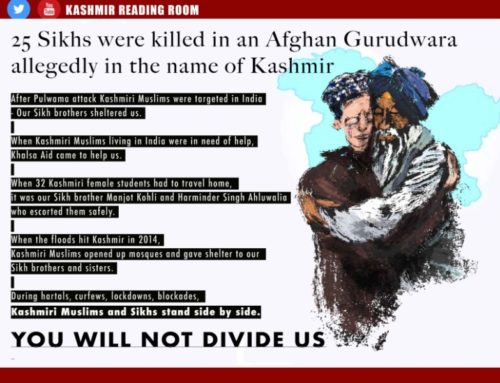

While reconciliation still remains an ongoing process, both communities have worked hard to move past this horrific event, repairing the ruptures it left in its wake and building solidarities. Most respondents, Sikh or Muslim, are quick to point out that relations have now normalized between the two communities. Asked if she’s afraid of a repeat of 2000, one female respondent from Chittisinghpora replied, smiling, “They ask, ‘why should we kill our Sikh brothers?’. Even in this heightened militancy, they haven’t let any harm come upon us. When they (the mujahideen) kill the police, they don’t see whether he is Muslim or Sikh”.

For Sikhs and Muslims in Kashmir, solidarities are based not on “an enforced commonality of oppression”, as Chandra Mohanty writes, but on the recognition of diversity and difference as central values “to be acknowledged and respected, not erased in the building of alliances”. To an outsider, it might be strange that they won’t eat at each other’s homes; but to them, these are simply ways of life to be respected. As several respondents explained, “we have tea in each other’s homes, but not food. We even attend each other’s weddings, but instead of serving them food, we sometimes give them a living chicken [so they can cook it how they like]”, because of religious rules governing the consumption of meat.

These alliances are also important because they help maintain peace on the ground, and in a context of pervasive violence and uncertainty make day to day living and safety possible for both communities. There are also important economic interdependencies that need to be maintained, as Nanak Singh explained. “All the labour here is Muslim. We cannot live without them and they cannot live without us”.

As for the conflict itself, the Sikhs as a community maintain a position of ‘neutrality’, meaning that they neither side with the militants, nor the Indian state. Perhaps this explains why while I expected violence to be central to discourses of everyday life, it was in fact discussed sparingly in my interviews. Instead, in almost all interviews, my respondents chose to discuss economic grievances arising from the limited economic opportunities in the Valley especially for young Sikhs, alleged discrimination in favour of other communities for representation in government positions, lack of political representation, the day to day inconveniences caused by frequent shutdowns and most importantly, the (perceived) threat of intermarriage between Sikh girls and Muslim boys.

Remaining Rooted

Despite experiencing violence, for many Sikhs, leaving was never an option. According to Pashaura Singh, not leaving Kashmir came down to two things – land ownership and government jobs. For others such as Darbara Singh, there was no question of leaving behind the land where his father’s blood had been spilled. Gurpal Singh, father of two young girls, who lost several family members in the ‘Kabali raid’, too felt that leaving would amount to a betrayal of the ancestors who had sacrificed their lives. And still for others such as Dimpi Kaur, whose husband was killed in the massacre, there simply was nowhere else to go.

One group of young Sikhs, who ally themselves with a Sikh missionary organization, recalled India’s actions in neighboring Punjab in 1984, when security forces had desecrated and attacked the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, to apprehend Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the man who became the face of the Punjab insurgency. The young Sikhs of this group believe that until India rights its wrongs in Punjab, the Sikh religious way of life will always be under threat in India. They explained that in Kashmir, they felt respected because should anything untoward happen to the community, “the leaders come within minutes and apologize”.

Regardless of the reason, the Sikhs chose not to leave, the Sikh position in Kashmir is one of simultaneous visibility and invisibility, whereby in times of crises, the community keeps a low profile while during periods of safety, it mobilizes.

Implications of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act

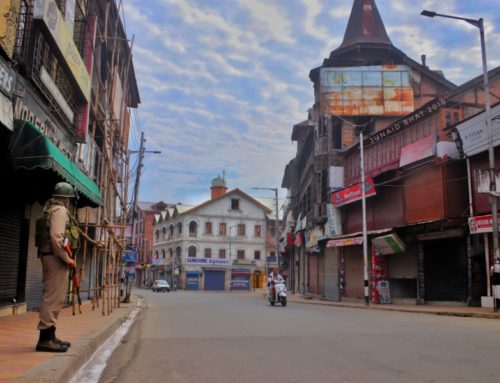

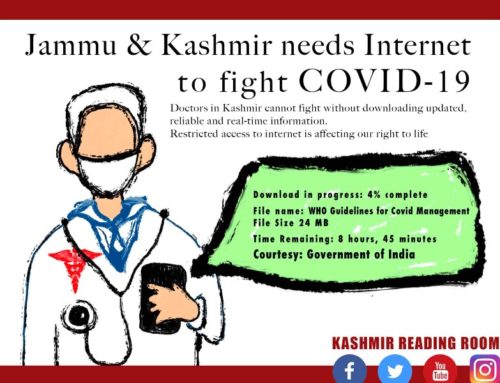

While the move was celebrated by many, the de-operationalisation of Article 370 has only prolonged the hardships of Kashmiris whose voices have been stifled through a variety of means, not least of all an internet blockade which has now become the longest in the world in a democratic nation. Although rapid changes are underway across Kashmir, such as the grant of domicile certificates to outsiders who meet the new criteria outlined by the J&K administration, the implications of these changes are difficult to assess for Kashmiri Sikhs, given the restrictions in mobility and communication and fear of reprisal that many express.

A consistent grievance of the Sikhs, there was little representation in government positions before abrogation. According to several respondents, Sikh youngsters have a difficult time obtaining coveted government jobs in Kashmir. Many respondents complained, saying that if there are 10,000 posts, “only one is for a Sikh”. With jobs across Kashmir now open to non-Kashmiris, there is fear that this will further dilute Sikh representation. A recent government order which calls for a 4% reservation for “Pahadi-speaking people” has deliberately left unaddressed what languages come under this classification, with Sikhs arguing that their dialect of Punjabi, is in fact, a Pahadi language. The order drew widespread condemnation from the community. A geographically dispersed and numerically minuscule community, the Sikhs don’t constitute an important enough ‘vote bank’ for the political leadership in Kashmir and are often left to advocate on their own behalf.

Another grave concern is the ongoing cycle of violence that despite Modi’s claims of having brought the militancy to an end, seems to have picked up in recent months. Although Sikh-Muslim solidarities exist, they are vulnerable to breaking down time and again, as they did in the months after Chittisinghpora. A series of recent events outlined below, has already attracted communal backlash from certain sections of the community and heightened the sense of vulnerability. With little to no hope of justice from the Indian state, these events, if left unresolved, can potentially weaken the already fragile solidarities between these communities.

On March 14, 2020, a Sikh police officer named Davinder Singh was arrested by the Jammu and Kashmir police, on the charges of aiding and abetting terror activities in the state. Mere days after his arrest, news reports alleging that he was a ‘double agent’ working for Indian intelligence, surfaced. Singh was implicated to be connected with Afzal Guru; a Kashmiri Muslim sentenced to death on February 9, 2013 for his alleged involvement in the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament. On June 19, 2020, Davinder Singh was granted bail by Delhi police, because the Delhi police had not filed a charge sheet within the stipulated 90 day period for doing so. However, Singh remains in judicial custody.

The Davinder Singh episode has once again raised the prospect of ‘deep state’ involvement in destabilizing Kashmir. The questions raised by this case are a stark reminder that Kashmir, as reporter Barry Bearak wrote of Chittisinghpora, “has a way of boiling truth into vapor. Every fact is contested, every confession suspect, every alliance a prelude to some sort of betrayal”. In the months that followed Chittisinghpora, that story too became complicated by a web of contradictions that remain unresolved.

On March 25, 2020, a dastardly attack on Afghanistan’s Sikh community in capital Kabul was purported to be revenge for “what had been done to Kashmir”. The attack, while denounced categorically by Kashmiris worldwide, again stands to communalize this relationship, as noted by a statement released shortly afterward by the advocacy group Stand With Kashmir (SWK).

This was followed two months later by a theft from a Srinagar gurudwara of Rs 2 lakh, and around the same time an attack on a Shia shrine, prompting a respondent (Kashmiri Muslim) to remark, “this seems like a return to the 90s” when at its peak, minorities began to become the target of the militancy.

Lastly, the death of a Sikh police officer from Pulwama, Anoop Singh, whose elder brother Sagar Singh too had been killed in counter-insurgency operations in Srinagar on December 9, 2009, and the heartrending photos of his family that circulated afterward, did much to arouse the anger of the Kashmiri Sikh community. While the officer was killed in the line of duty, his death was a stark reminder that unlike the Modi government’s claims that abrogation of the ‘special status’ of Kashmir would curtail militancy, the struggle for Kashmiris on all sides is far from over.

References

- (29 June 2019) Statement by Ram Madhav, BJP National General Secretary. ‘J&K: Article 370 has to go lock stock and barrel, says Ram Madhav’. Indian Express, Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/jammu-and-kashmir-article-370-bjp-ram-madhav-58)

- For the text of the act, see The Gazette of India Extraordinary. ‘The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019’, 08/09/2019, http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/210407.pdf

- Within moments of the declaration by India’s Home Minister Amit Shah in Parliament, advertisements promising “heavenly” plots of land for sale in Kashmir went up on the web and RSS karsevaks (volunteers within the organization) appallingly, remarked, that they can now ‘bring beautiful Kashmiri girls’ as brides; IANS (7 August 2019 ) ‘Marry fair Kashmiri women now’: BJP MLA after Article 370 repeal’. Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/marry-fair-kashmiri-girl-now-bjp-mla-after-on-article-370-repeal/story-PN1M8vLCWdizTpGFuykWyI.html

- For Kashmiri Pandit families that continued to live in Kashmir, see Trisal, N. (2007). Those Who Remain: The Survival and Continued Struggle of the Kashmiri Pandit “Non-Migrants”. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 5(3), 99-114

- The first Sikh guru and the founder of Sikhism in 1469, Guru Nanak traveled to Kashmir in the year 1516

- Guru Hargobind’s visits to Kashmir are placed at around 1620 AD, according to the Sikh encyclopedia, Sikh Wiki. Retrieved from https://www.sikhiwiki.org/index.php/Guru_Hargobind_Sahib_in_J_%26_K

- For a detailed account of the ‘Kabali raid’, see Whitehead, Andrew. “Partition Voices: The Bali Family”, BBC Radio (2003), Retrieved from https://www.andrewwhitehead.net/partition-voices-bali-family.html; ‘The forgotten massacre that ignited the Kashmir dispute’. Aljazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/forgotten-massacre-ignited-kashmir-dispute-171106144526930.html

- Census of India, “Religion”, 2011, https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/jammu+and+kashmir.html

- Geelani, Gowhar. (2019). Kashmir: Rage and Reason. New Delhi: Rupa.

- (19 January 2016) ‘Exodus of Kashmiri Pandits: What Happened on January 19, 26 Years Ago?’, India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/fyi/story/exodus-of-kashmiri-pandits-january-19-jammu-and-kashmir-304487-2016-01-19

- Bhat, A (Ed).(2003) Kashmiri Pandits: Problems and Perspectives. New Delhi: Rupa.

- While scholars put the number of displaced at approximately 170,000, Kashmiri Pandit leaders estimate closer to 300,000 were displaced. Trisal, Nishita. (2007) “Those Who Remain”, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 5, no. 3, pp.99-114.

- ‘Agencies’ refers to Indian (and international especially Pakistani, American and Russian) intelligence and espionage bodies like the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) as per respondent interviews.

- There has only been one inquiry related to Chittisinghpora, whose contents were never made public. It was also later discredited when new facts emerged. In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, most Sikhs believed that it was militants who carried out the attack. However, as the facts became murkier, most people started to think this was the work of the ‘deep state’. This is now a pervasive belief in Kashmir. In nearly all of my formal interviews and informal conversations, I was told that this was the work of ‘agencies’. Jaleel, M. (20 August 2017) “Why justice eludes the victims of Pathribal fake encounter?”, The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/why-justice-eludes-the-victims-of-pathribal-fake-encounter-4804985/

- Except where indicated, all respondent names have been changed to protect their privacy

- Author interview, Nanak Singh, Chitti Singhpora village, 9th August 2017.

- This number was given to me by my respondents. As per the Jammu and Kashmir Revenue Department, a total of 1714 families, or 6504 souls, have left Kashmir and are registered as migrants in Jammu since the 1990s. Statistics retrieved from http://jkmigrantrelief.nic.in/. Last accessed 07/08/2020.

- Author interview, Nanak Singh, 06/18/2018

- Author interview, Bitti Kaur, 06/19/2018.

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade (2003). “Introduction: Decolonization, Anticapitalist Critique, and Feminist Commitments”, in Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity; p. 7.

- Author interview, Nanak Singh Bedi, 08/09/2017.

- Singh, J. (8 March 2020). ‘Sikh Kashmiris react sharply to Pahari speaking people reservation circular’. The World Sikh News. Retrieved from https://www.theworldsikhnews.com/sikh-kashmiris-react-sharply-to-pahari-speaking-people-reservation-circular/

- Chaturvedi, S (14 january 2020). ‘Davinder Singh Arrest Raises Many Questions. How the NIA Handles It Could Raise More’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/security/davinder-singh-afzal-guru-nia

- (19 June 2020). ‘Bail granted to suspended J&K police DSP Davinder Singh as Delhi Police fails to file chargesheet’. National Herald. Retrieved from https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/india/bail-granted-to-suspended-jandk-police-dsp-davinder-singh-as-delhi-police-fails-to-file-chargesheet

- Bearak, B (31 December 2000). ‘A Kashmiri Mystery.’ New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/31/magazine/a-kashmiri-mystery.html#:~:text=As%20it%20happened%2C%20several%20men,Kashmir%2C%20such%20things%20are%20possible.

- Mir, S (26 March 2020). ‘#NotInMyName, Say Kashmiris After ISIS Claims Kabul Attack Was Revenge for Kashmir’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/security/notinmyname-say-kashmiris-after-isis-claims-kabul-attack-was-revenge-for-kashmir

- SWK. ‘Statement of Solidarity with the Victims of the Kabul Massacre’. https://www.standwithkashmir.org/kabul-massacre. Last accessed 07/07/2020

- KNT (30 May 2020). ‘Money stolen from Jawahar Nagar Gurudwara’. Fast Kashmir. Retrieved from https://fastkashmir.com/2020/05/money-stolen-from-jawahar-nagar-gurudwara/

Hussain, A (22 May 2020). ‘Slain Kashmiri Sikh cop second of 4 brothers to lay down life in militant attack’. HindustanTimes. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/slain-kashmiri-sikh-cop-second-of-4-brothers-to-lay-down-life-in-militant-attack/story-LwKxOpdGFkYUA7X7U1dshJ.htm

About the Author: Khushdeep Kaur Malhotra is a 6th year Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University, Philadelphia. Her dissertation examines the political and cultural economies of mobilities in conflict. Data for this report are retrieved from ethnographic fieldwork she completed with the Kashmiri Sikh community from March 2018-March 2019.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.