Enforced Homelessness

Collective dispossession and punishment in Kashmir

Mariyeh Mushtaq

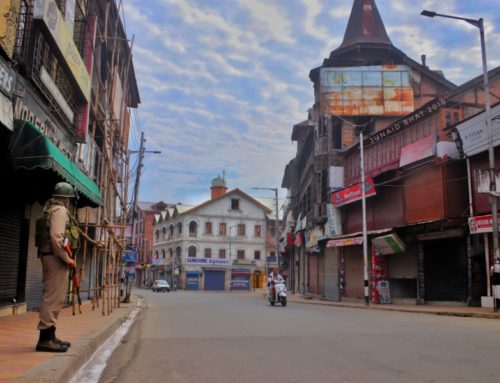

On May 19, 2020, over 14 houses were burned down in a locality of Nawakadal, Srinagar by the Indian armed forces whilst carrying out a gunfight with two militants, who had taken shelter in the area. The residents alleged that apart from razing their houses to the ground, their valuables like gold, cash, etc. were stolen by the armed personnel during the encounter.

Videos and photos of women wailing and crying at the theft of gold jewellery from their damaged homes surfaced on the internet. In the videos, the women can be seen pointing out the broken lockers and the empty jewellery boxes to the journalists. More recently, after the Reban encounter, videos of children looking for the torn pages of their school books buried underneath the shattered bricks of what they called home also made rounds on social media. Subjecting Kashmiris to this form of collective punishment is not new. The destruction of civilian property is as normalized as is the killings of civilians. Jammu & Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society’s annual reports from 2016-2020 provide detailed documentation of the destruction of property by the Indian armed forces with absolute impunity.

I spoke with two families from a village in north Kashmir whose houses were burnt down during an encounter in 2019. The encounter had lasted over 70 hours. Akhtar (name changed), a 52-year-old woman, said that shortly before the encounter, all the villagers were asked to vacate the houses in the mahalle (locality) where the militants were apparently hiding. She lives in a joint family and said that they were separated in this sudden pandemonium. “For three days, I didn’t know the whereabouts of my family, I was praying for their safety the whole time… especially after we heard the sound of IED blasts, I knew that doom had befallen on us”, she added.

Encounter in Kashmir is also a site of plunder, loot, and theft. Akhtar’s daughter Rubeena, 28, told me, “When we came back to our home after 3 days, we found out that our cow-shed and storeroom had been torched to the ground and all of our ration had also been spilled on the floor. They had taken our 5-litre oil tin and sprayed it all over the floor and the walls. Our bistar (bed) was tossed upside down, everything was upside down. It was like a tornado, my mother fainted at the sight of it”. Many reports suggest that the forces have been involved in the plunder of the empty homes caught in the midst of gunfights. The authorities deny these allegations each time they are raised. Kashmiri homes continue to be collateral damage much like the bodies which inhabit them.

In recent years, the frequency with which destruction of property has been carried out at the encounter sites warrants more focused research in order to gauge the total damage and the cost incurred by the victim families.

As the 2019 JKCCS report noted:

The vandalism and destruction of window panes, people claimed, were to impose collective punishment and to dissuade the people from protesting – particularly against the abrogation of Article 370, 35-A and splitting the J&K state into two separate Union Territories.

…use disproportionate force to inflict damage on a civilian property, sometimes resulting in the death of civilians as well, as the killing of 12-year-old Atif Mir reveals. (p.39)

Recounting the horrors of experiencing an IED blast in her neighbourhood, Mehreen said, “when they (blasted) the house, we could feel our home, which was half a kilometer away, shiver and shake. It was as if our house was scared too, just like us. They say that during the blast, the tremors are so powerful that if you have a baby you must put something in their mouth otherwise their teeth can fall out due to the impact”

The villagers recalled that the cowshed was burnt as well, while the cow was trapped inside. “When the army left, we went to the site. Everything was reduced to dust and in the corner we saw a burnt carcass of the cow. It was a devastating sight. Everyone in the village had a heavy heart that day.”

After the encounter is over, the locals come together for fund-raising campaigns to collect relief, in cash and kind for the victim families. Because of the informal nature of these initiatives and processes, no work has been done to assess the extent to which these campaigns help, the families rebuild their home, and how long it takes. In the case of the aforementioned Nawakadal incident, the locals were able to collect over 3 cr in one week following the encounter. But it is not clear whether the funds are enough to rebuild all the destroyed/damaged property.

The trauma associated with enforced homelessness is related to both material loss and emotional distress. It seeps into the psychological and mental well being of the victims. Often these (now shelterless) families take refuge in the homes of their relatives or neighbours, leaving the women and girls particularly vulnerable to abuse and harassment. No study has been conducted to investigate such cases.

In order to estimate the extent of losses Kashmiris have incurred in the last thirty years due to damage to property in ‘conflict-related’ encounters, I filed an RTI application in June 2019.

2019 RTI

Considering the lack of information available on the exact number of buildings damaged in the ‘turmoil of Kashmir’, a Right to Information (RTI) application to the PIO, District Commissioner Office was filed in 2019. I sought details of damaged buildings classified as government-owned and civil. I also sought details on the extent of losses (in monetary terms) and the compensation (or lack thereof) received by the families. Letter no. ACR/RTI/19/1759 dated 30.05.2019 was received and redirected to offices in five districts of Kashmir. The findings are discussed below:

Srinagar:

Dated:13.06.19

Incharge Relief Section

- Ex-gratia relief has been sanctioned in respect of 2953 cases.

- The loss assessed is being done by concerned engineering authorities, however, Ex-gratia is sanctioned on the basis of 50% of loss assessed subject to an upper selling of Rs. 1.00 lac

- INR 13,07,42,513 has been sanctioned to the affected persons so far.

Hajin

Dated: 24.06.2019

Tehsildar Hajin

- Two Residential houses got damaged related to turmoil in Kashmir valley in respect of Tehsil Hajin which was established in 2014

Ganderbal

Dated: 25.06.19

Assistant Public Information Officer, Ganderbal

- How many houses/other buildings got damaged: 48

Bandipora

Dated: 09.07.19

Dy.SP Bandipora

- 217 property damage cases were received by the respective police stations

Sumbal

Dated: 24.7.19

Tehsildar Sumbal, Sonawari

- 320 structures damaged since 1989

- 67 persons have been paid compensation

- INR 70, 50,000/- estimated loss (approx.)

- INR 14, 19503/- for 67 Asamies has been paid by DC office Bandipora

Budgam

Dated: 16.10.19

Dy SP (Hqrs) Budgam

- How many houses/other buildings got damaged: 1419

Interestingly, one of the response letter dated 02.07.2019 (from PIO, Srinagar) misread the RTI which sought information ‘related to turmoil in Kashmir valley since the inception of militancy from 1989 to till date’. The PIO instead responded to ‘damages to houses and Govt/Civil buildings due to militancy since 1989’. The information given was:

|

No. of residential homes: 156 | No. of Govt Buildings: 48 | No. of Civil Buildings: 46 |

Most of the other information supplied did not present any specifics. In fact, no information was divulged. The reason cited for not divulging this information was that it ‘pertained to the revenue department and the concerned quarter’. Nevertheless, it is clear even from the figures cited by the government that the rate of compensation remains significantly low. This could also be a result of the fact that no complaint is allowed to be made if the authorities claim that the family had voluntarily given shelter to the militants. It must be noted that no substantiation is required at any stage of the process, for these claims made by the authorities.

In the past few years, due to the disturbing rise in military operations, enforced homelessness has increased alarmingly in the region and is at its highest since the 1990s. The prevalence of this kind of ‘collective punishment’ leads one to conclude that this is a concerted strategy to discourage the masses from protesting against grave human rights abuses in the region. By destroying homes with institutional impunity and rendering families homeless, the Indian state’s agenda of disenfranchising Kashmiris becomes even more clear. How is it that the destruction of homes of Kashmiri Pandits invokes collective empathy and outrage whereas the sight of Kashmiri Muslim homes being demolished hardly makes a case of sorrow in the Indian imagination?

About the Author: Mariyeh Mushtaq is an independent researcher based in Srinagar, Kashmir. Her research analyses the intersection of gender, militarization and precarity with a focus on the disputed region of Kashmir. She recently completed her Masters in Gender, Sexulity and Culture at Birbeck University of London. At present, Mariyeh is working on two projects related to research and documentation of the socio-cultural impact of militarization in Kashmir.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.