Ecological Vandalism in J&K:

The After-effects of Abrogating the Special Status

By Sushmita

“Ann poshi teli yeli wan poshi (food will last as long as forests last)” is a popular Kashmiri saying that gives an insight into the important connection that Kashmir has had with its forests. Having a delicate ecological balance, Kashmir’s evergreen and lush forests have a direct bearing1Jammu and Kashmir State Forest Policy, 2010. Retrieved from http://jkforest.gov.in/pdf/approved_forest_policy_28jan11.pdf on the region’s agriculture and energy sectors. Despite the well understood relevance of these forests, even popularised in the teachings of saints and poets like Sheikh ul Alam, the forests have faced unprecedented devastation alongside the cycle of physical violence and militarisation in the last three decades.

Moreover, as part of abolishing the semi-autonomous status of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), the union government passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act in the Indian parliament. The Act has been in effect since October 31, 2019. As per this Act, 153 Acts of the former state of J&K have been repealed, 166 Acts have been retained from the former state and 106 new laws have been applied to J&K. However, there has been a lack of clarity on which Indian laws are applicable and which have been implemented. For instance, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 has been made applicable but not implemented. Before the amendment of Article 370, the state’s forests were governed by the Jammu and Kashmir Forest Act 1987, which some believe was a robust law to protect the region’s forests.

Fast paced forest clearances post amendment of Article 370

As per a 2017 report2 FSI assesses forest cover of the country every 2 years by digital interpretation of remote sensing satellite data and publishes the results in a biennial report called ‘State of Forest Report'(SFR). Beginning in 1987, 16 SFRs have come so far. of the Forest Survey of India, forest cover in J&K increased with a net gain of 253 sq. km in comparison to the forest cover in 2015. However, experts3Parvaiz, A (12 December 2019). ‘Kashmir’s forests face the axe’. Thirdpole.net. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2019/12/12/kashmirs-forests-face-the-axe/ claim that out of 253 sq. km increase in forest area, a significant figure of 245 sq. km comes from outside the Line of Control (LOC). India officially claims the area and includes it as Indian territory in its maps despite it being under Pakistani administration since 1948.

The area under dense forests around Pahalgam in South Kashmir, which also happens to be a tourist destination, fell by 191 sq. km from 1961 to 2010 with an average annual loss of 3.9 sq. km, mainly due to illegal constructions. The districts that showed an increase in forestation namely Budgam (61 sq. km), Baramulla (34 sq. km) and Pulwama (21 sq. km) did not see an actual increase in the forest area, but a shift to horticulture.

In a span of 33 days between September 18, 2019 and October 21, 2019, the Forest Advisory Committee (FAC), a statutory body which rules over the questions on the diversion of forest land for non-forest use in the state, approved diversion of over 727 hectares of forest land. It also approved felling of more than 1800 trees, which were unenumerated.4 Ibid.

Importantly, 60 percent of the diverted land was approved for diversion for construction of roads. 33 percent (243 hectares) of the diverted land was approved for diversion for the utilization of army and paramilitary forces in Pirpanjal (Gulmar Wildlife Sanctuary), Jhelum Valley, Samba and Jammu Forest divisions, as per the analysis of official documents.

Moreover, a review of official data revealed that a massive land hunt5 Parvaiz, A (8 January 2020). ‘Forest Land identified for development after reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir’. Wire.in. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/government/forest-land-jammu-and-kashmir[/mfn] exercise has been going on in the region. So far 120000 kanals (15000 acres)5Ibid. land from 203020 acres of state owned land in Kashmir region has been identified for industrial infrastructure development. Understandably, most of this land is ecologically sensitive as it’s part of or close to rivers, streams and other water bodies.

What comes across more starkly is that a significant proportion of forest land/s diverted is for the use of army and paramilitary forces. 33 percent (243 hectares) of 727 hectares of forest land was approved for such diversion between September 18, 2019 and October 21, 2019 in Pir Panjal (Gulmarg Wildlife Sanctuary), Kehmil, Jhelum valley, Samba and Jammu forest divisions.

Official reason for such rushed decisions was – because of the implementation of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act from October 31, 2019, the Jammu and Kashmir Forest would be scrapped.6 Ibid.

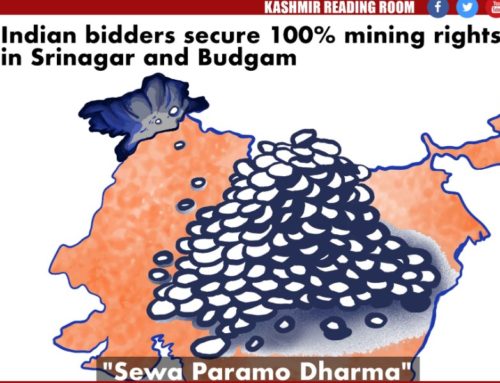

Sand mining

In February 2020, going against its own studies that warned against large scale mining operations in the Jhelum river and its tributaries, the government started the process of opening up as many as 200 blocks in the river for mining of sand and other minerals.

In a report from 2018, prepared by the Central Water and Power Research Station (CWPRS) on the request from Department of Irrigation and Flood Control (IFC), the situation of the river was highlighted

“The dredging/desilting/sand mining of the main channel of Jhelum from upstream to Asham is not advisable and may cause difficulties for the flood management. Re-sectioning by increasing the waterway width may possibly be taken up at few places only as recommended in the tour report of CWPRS officers.” The study was supported by the World Bank.

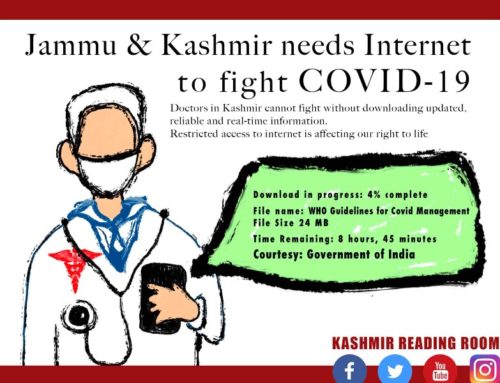

Despite several recommendations issuing alerts on the fragile and delicate situation of the river, mineral blocks in the Jhelum and its tributaries were auctioned starting December7 Ahmad, M (25 June 2020). ‘Kashmir: Online bidding for mineral blocks leaves locals at a disadvantage’. Wire.in. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/government/kashmir-jhelum-mineral-blocks-bidding-online 2019. In wake of the internet shutdown and slow internet speed mainly non- Kashmiris were successful in these auctions. Shockingly, a member of Environmental Appraisal Committee of J&K which gives environmental clearance to mining and other projects, told thirdpole.net8Thethirdpole.net is a magazine covering issues related to the environment. on the conditions of anonymity that they had “advised the government in a meeting in December last year that no mining should be allowed in Jhelum and other rivers till there is a basin wise scientific mining plan as to which area should be declared feasible for mining and which areas should be declared as river sanctuaries.”9Ibid.

Kashmir saw its worst floods in 2014 and now experts fear that intensive mining will leave an impact on local ecology as also on flood management in Kashmir.

Data deficient

Himalayas is one of the most data deficient areas10Parvaiz, A (11 October 2019). ‘Kashmir communications ban hits key climate studies’. thethirdpole.net. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2019/10/11/kashmir-communications-shutdown-impacts-key-climate-studies/, compared to other mountain regions. Studies on climate change and environment in the region have suffered due to the lockdown. It has also meant that the continuity with which data was being collected has broken.11Javeed, A (29 November 2019). ‘Kashmir’s famous Dal Lake suffers during political uncertainty’. Thethirdpole.net. Retrieved from https://www.thethirdpole.net/2019/10/11/kashmir-communications-shutdown-impacts-key-climate-studies/

How have new policies affected the state?

There is a wide consensus among the residents and experts in the region that the new forest laws under the J&K Reorganisation Act, 2019 are ineffective. Nadeem Qadri, an environment lawyer and executive director of Centre for Environmental Law said, “Laws in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir were more robust, as they were based on Maharaja’s principle of natural resource management and conservation.”12Javeed, A (9 June 2020). ‘Timber smugglers loot Kashmir’s forests during lockdown’. Eco-business. Retrieved from https://www.eco-business.com/news/timber-smugglers-loot-kashmirs-forests-during-pandemic-lockdown/

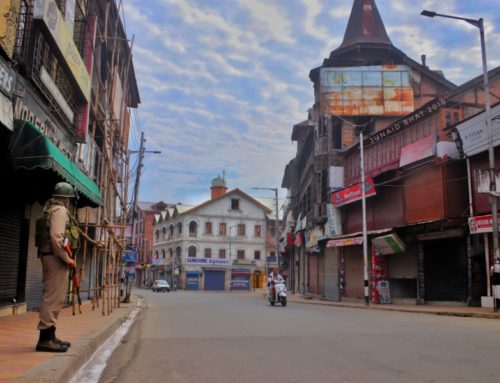

This kind of mismanagement and confusion paved the way for timber smuggling during the Covid lockdown which has coincided with the ongoing communication blockade in Kashmir post the amendment of Article 370. Reports documenting an increase in the number of forest offences have emerged.

In another development the J&K General Administration Department (GAD) accorded sanction to the creation of Jammu and Kashmir Forest Department Corporation (JKFDC) as a registered company in the UT after repeal of Jammu and Kashmir State Forest Corporation Act 1978.13GK News Network (24 June 2020). ‘Government clears creation of forest dept Corp as company’. Greater Kashmir. Retrieved from https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/jammu/government-clears-creation-of-forest-dept-corp-as-company/

The status of nomadic and tribal communities

As per 2011 census, Scheduled Tribes form 11.9 percent of Jammu and Kashmir’s population. However, tribal rights activists in the state claim that Gujjars and Bakarwals constitute upto 20 percent of the 12 million population.14 Parvaiz, A (16 January 2020). ‘Tribal population of Jammu and Kashmir cries foul about non-implementation of Forest Rights Act. Mongabay. Retrieved from https://india.mongabay.com/2020/01/tribal-population-of-jammu-and-kashmir-cries-foul-about-the-non-implementation-of-the-forest-rights-act/ Gujjars and Bakarwals are the nomadic tribes of Kashmir. As March approaches, many of the tribespeople move15Sushmita (19 April 2018). ‘EXCLUSIVE! Implement Forest Rights Act to Protect Bakarwals of Kathua: Talib Hussain’. from the plains (Jammu) and other areas towards Kashmir. The tribe has lived in precarious conditions and some have even been forced to resort to begging for their survival. Traditionally, Gujjars were responsible for dairy business, while Bakarwals took care of the cattle. It is widely known that the tribal communities guard the forests and protect them from timber mafias.

Bakarwals have faced double oppression because of the ongoing conflict in Kashmir. Apart from suffering persecution in forests by armed personnel16 Supra note 235., they routinely face the issue of closing down of pastures due to security reasons.

Under the FRA, traditional forest dwellers are protected against forced evictions and their tenurial and customary rights (the right to graze cattle etc.) are recognized. However, a narrative has been created that if Gujjar Bakarwals (mostly Muslims) get rights under the FRA, it may lead to a demographic change in the area (mainly Jammu, Kathua, Sambha). Such narratives are fuelled by former-BJP ministers like Lal Singh, who had previously opposed the implementation of the Act. This has been one of the main impediments in the recognition of the rights of the tribal communities.

FRA also places the decision to carry out development projects in tribal regions with local bodies like Gram Sabhas. A narrative against tribals, as is common elsewhere too, has been created that they are encroachers and cattle smugglers, even though their co-dependence on forests and their role in preserving forests has been widely documented.

Conclusion

The rapid policy decisions being taken to clear long standing forests, especially for projects which were so far still under consideration may have a far-reaching impact on the delicate ecological balance of the region and may accelerate climate change. That the locals are completely shut out from the decision-making processes adds salt to injury. While regressive laws are implemented, the work to implement progressive laws like FRA has not even started. The lack of access to the region for purposes of independent research and reporting is another cause for concern as there is a huge vacuum of competitive and rigorous research on the impact of increasing pollution and land diversions for projects related to militarization and more.

About the Author: Sushmita is a Mumbai based independent researcher working on issues of forest and agrarian rights, gender-based violence, etc. She has been a part of an on-going assessment analysing the impact of COVID-19 on tribal communities.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.