Dismantling Land Reforms in J&K

Land Grab under the Garb of Developmentalism

By Shinzani Jain

The Government of India recently abrogated the special status accorded to the erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) under Article 370 of the Constitution of India. One of the main reasons cited by Home Minister Amit Shah while introducing the resolution in the Rajya Sabha on August 5 was that Article 370 has hampered the development of the people of J&K. Soon, this became a popular opinion.

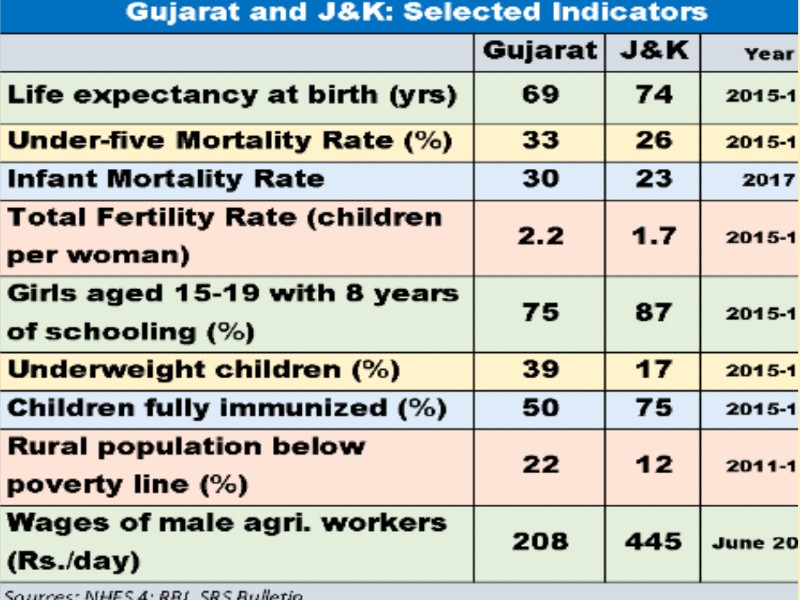

Criticising this widely popular move, renowned economist and academic Jean Dreze voiced his dissent arguing, “It is not correct to say that Kashmir is a backward state, therefore, it was a must to remove Article-370. Of course, there are economic problems, but the living standard is quite good, nutrition is much better in Kashmir than Gujarat.1Dreze, J (9 August 2019). ‘Economist Jean Dreaze: Article 370 helped reduce poverty in Jammu and Kashmir’. National Herald. Retrieved from https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/india/economist-jean-dreze-jandk-more-developed-than-gujarat-special-status-helped-reducing-poverty. Dreze notes that J&K is, in fact, more developed than many of the other Indian states. He also makes a comparative analysis between the human development indicators of J&K and Gujarat.

Interestingly, Dreze attributes the better performance of J&K to the extensive land reforms that were carried out by the National Conference government in the 1950s and contends that it was, in fact, Article 370 that made these reforms possible. He says, “Because of Article-370, J&K has its own constitution and this constitution allowed distribution of land which the Constitution of India would not have allowed. I think it played an important part in reducing poverty and in laying the foundation of a relatively egalitarian economy in rural areas.”2Ibid.

Sharply critical of the government’s move, former Finance Minister of J&K, Haseeb A. Drabu writes, “For the people of J&K, the biggest benefit of the state having greater legislative latitude under Article 370 has been the radical restructuring of agrarian relations. It was the first state in India, much before the communist government in Kerala, to carry out non-compensatory land reforms.”3Drabu, H. A (8 August 2019). ‘Was special status a development dampener in J&K?’. Live Mint. Retrieved from https://www.livemint.com/opinion/columns/opinion-was-special-status-a-development-dampener-in-j-k-1565248797810.html. J&K was, in fact, the only state to carry out land reforms without granting any compensation to former proprietors of land. Land was transferred to peasants free of costs and arrears.

Land reforms in Jammu & Kashmir

Land reforms in J&K constituted a part of a spate of reforms, including health, education and agrarian reforms, introduced by the National Conference government between 1948 and 1976. Two major legislations through which these reforms were affected were – the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950 and the J&K Agrarian Reforms Act, 1976. Under the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, the upper limit for landholding was reduced to 22.75 acres in 1950, which was further reduced to 12.50 acres through the Agrarian Reforms Act, 1976. All land in excess of the ceiling was expropriated by the state and was then transferred to the actual tillers. The decision on compensation was taken later in 1951 by the Constituent Assembly of the state which decided against paying any compensation to landlords.4Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly Debate, Part I, Vol. I (1951-1955). It was their belief that the system that resulted in this kind of stark disparity in land ownership was deeply exploitative and parasitic, and neither the state nor the beneficiaries of the reform owed compensation to the landlords who had benefited from this exploitative structure for centuries.

These reforms, as first envisioned and articulated by the leaders of the National Conference, were introduced by them in the Naya Kashmir (New Kashmir) Manifesto in 1944. The basic principles informing these land reforms – ‘abolition of intermediaries’ and ‘land to the tiller’ – were proposed in Naya Kashmir. J&K was the only state in independent India that refused compensation to landlords whose lands were expropriated by the state. These reforms were further supplemented with elaborate tenancy reforms.5Moza, M (1985). Agrarian Relations In J&K: A Case Study of Two Districts. Jawaharlal Nehru University: New Delhi

Naya Kashmir was launched by the leaders of the National Conference in 1944. This document laid down a comprehensive plan for socio-economic, political, and cultural reconstruction of the state of J&K. Drawing inspiration from the Soviet model, Sheikh Abdullah declared the vision that was being laid down for the newly emerging state would be socialist. He emphasised that real freedom is possible only after economic emancipation of the people. With this leaning, he resolved to build the foundation of democracy in the state on the bedrock of economic equality.

The remarkable nature of land reforms can be assessed by contextualising it within the socio-political background of J&K during the Dogra rule. The state economy was predominantly agrarian with 80% of the peasantry constituted by Kashmiri Muslims. In her book ‘Languages of Belonging’, Chitralekha Zutshi details how, over centuries of rule under the Afghans, Mughals, Sikhs and Dogras, landownership in the region had become deeply skewed, with the majority of Kashmiri Muslim peasantry working as landless labourers. The people of Hindu community ascribed as ‘lower caste’ were placed similarly or worse. While this was the condition of the vast majority, exorbitant amount of lands came to be owned and controlled by Kashmiri Pandits and the Kashmiri Muslim communities of Syeds and Peers.

What is the relationship between these reforms and Article 370? Drabu argues that when the J&K government divested the landed aristocracy of their land under the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act in 1950, the right to property was a fundamental right under Article 19 of the Indian Constitution and it was the autonomy under Article 370 thereof which prevented the annulment of this statute. Because of the existence of Article 370 and the autonomy ensured thereunder, Article 19 of the Indian Constitution was not applicable to the State of J&K. The same logic was put forth first by the then Finance Minister of J&K, Mirza Afzal Beg, to turn down the demand for compensation by the landlords whose lands were expropriated.

Impact of Land Reform

In an essay in the book ‘The Radical in Ambedkar’, Dreze argues, “Radical land reforms in J&K were immensely popular and laid a lasting basis for a relatively prosperous and egalitarian rural economy, with very low poverty rates by Indian standards.”

Bhatia highlights how the Scheduled Caste (SC) community was numerically the biggest beneficiary of land redistribution in Jammu. Brecher approximates the number of SC beneficiaries in Jammu to be 2,50,000.Dr. Ashish Saxena notes that during 1950s-70s, out of the 672 kanals of surplus land taken away from Rajputs and Mahajans, 70.24 percent was allotted to tenants from SCs. This has resulted in an intergenerational shift in occupation pattern of the SCs from landless agricultural labourers to land-owning peasants from 0 percent landowning peasants in the grandfather’s generation to 47.1 percent landowning peasants in the present generation in Jammu.Linking the prevalence of poverty and hunger in India with a failure of land reforms in India, Iqbal argues that both Central and State governments in India could take a leaf out of J&K’s book to alleviate their people’s suffering.

According to Drabu, the factors underlying J&K’s better than national average human development indicators are that along with the land reforms, there was a massive debt write-off undertaken over a period of twenty years between 1951 and 1973. It is because of this that the incidence of indebtedness in J&K is at the second lowest. Landless labour in the state is nearly absent and land ownership translating into economic empowerment has led to more than 25% of the household earnings in J&K coming from own cultivation. As a result, the incidence of poverty in the state is remarkably low with households living below the poverty line at 10% against the all India average of 22%.

The case of land reforms in J&K and the consequent prosperity within the society and economy presents us with a unique example in the history of Indian subcontinent. Rather than an objective study on what made this possible, what we have witnessed in the past year is an enormous propaganda machinery not only systematically propagating misinformation and falsehood, but also meticulously working to shift the agenda and discourse of public policy.

Debunking Developmentalism

Land reform has been called the forgotten agenda of the 1960s. The phase of decolonization was marked by the new post-colonial regimes adopting and implementing land reforms during the 1950s and 1960s. In his book ‘Land to the Tiller: The Political Economy of Agrarian Reform in South Asia’, Ronald Herring notes that land reform was frequently the first legislative act of a new regime in an agrarian society. Few issues arouse a comparable level of political controversy, manipulation of symbols and administrative energies, he argues. Faced with massive challenges, these new regimes struggled to deal with the scale of rural poverty, agrarian distress, inadequate food production and an overarching possibility of rural unrest.

The dual policy logic behind land reforms can be classified as:

- Economic logic – the most rational and economic use of scarce land resources without any waste of labour and land. This logic warns against unproductive accumulation of land resources.

- Redistributive logic – redistribution of land resources in favour of the less privileged classes with a view to ending exploitation.

This policy logic to land reform is termed by Herring, as the dyad of social justice and productivity. He links this dyad to a third legitimation of agrarian reforms – the threat of rural violence. He highlights how ‘concern for rural tensions,’ ‘harmony,’ and ‘stability’ have dominated much of the policy logic, and land reforms frequently constituted the first legislative act of a new regime.

This influence can also be attributed to the simultaneously increasing influence of the communist ideology in the ‘Third World’ during the years of decolonization. Aijaz Ashraf Wani argues that this was a time when state-led developmentalism was favoured by the international environment and ‘development’ had become the major international concern since the emergence of ‘Third World’. The apprehension of International donor agencies and the US of the communist influence in poor countries pushed them to emphasising ‘state-led developmentalism’ as the essential means of modernizing and improving the conditions of people. This strategy of development has been attested to by the scholars of history of development planning of India. K B Saxena argues that land reform was conceived as a major instrument for increasing agricultural production and productivity, restructuring agrarian power relations and of alleviation of rural poverty, particularly of informal tenants and agricultural labourers and was pursued with full vigour by the Central Government.

However, the ‘development-policy’ discourse around land reform has undergone a paradigm shift since the era of decolonization. The current phase of land reform has its genesis in the overarching paradigm of the economic policy and ideology of neoliberalism. The discourse around developmentalism began to undergo a change after the arrival of the Reagan-Thatcher era with the emerging international paradigm of ‘equity’ and ‘growth’. Concern for the lowest 40 percent of the income pyramid, argues Herring, is currently in vogue due to this paradigm shift.

In his essay ‘Re-setting the Agenda of Land Reforms’, Professor K. B. Saxena notes that a reversal of the old architecture of land reforms has been taking place in India without a formal declaration. Post liberalisation, this is evident in the relaxation in ceiling provisions on agricultural landholdings for corporate bodies and aggressive official advocacy of liberalising tenancy. He adds, “There is virtual consensus among policymakers, neoliberal economists, agricultural scientists and experts from international financial organisations that the existing land reform policy on tenancy, ceiling, restrictions on transfer of land and change of land use poses serious constraints in achieving fast economic growth and realising optimal value.”

‘Developmentalism’ as contextualized by Wani has always been used by the Indian state as a tool to manage Kashmir. The political rhetoric of Indian leadership, for decades, has been that development will bring normalcy in Kashmir. Recently, the same rhetoric has been applied by the Indian state to effect the abrogation of the special status accorded to the erstwhile state under Article 370 of the Indian constitution.

The shift in public policy discourse is revealing of how the logic of the market has rendered the discourse hollow of principles of social justice. The social justice-productivity dyad is no longer dictating policy logic. Nor is there any fear of social unrest, as was the case according to Herring. The current ongoing shift in policy discourse is being done under the garb of welfarist motivations and J&K is the most recent casualty of it.

Land grab under the garb of Developmentalism

In order to protect land rights of the indigenous population of Jammu & Kashmir after land reforms, a regime of laws was enacted by the state. These laws prohibited the alienation of land to non-state subjects and corporate players from outside the state. Some of the laws protecting land rights of the state subjects were enacted during the regime of the Maharaja as a result of people’s struggles for employment and land rights. This framework of laws includes Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution and state legislations – J&K Alienation of Land Act, 1938, Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950, J&K Agrarian Reforms Act, 1976 and J&K Land Grants Act, 1960. Along with the revocation of the autonomy of the state, legislative and constitutional changes have been brought about by the central government to dilute this regime of laws protecting land rights of the people of the state.

Article 35A conferred the power on the state legislature to enact laws defining classes that will constitute permanent residents of the state and will be conferred with special rights and privileges with respect to employment and ownership of immovable property. It was, in fact, based on Maharaja’s Notification of 20th April 1927, issued as a result of demands by Kashmiri Pandits who feared loss of employment and security in wake of influx of people to the state from Punjab.

A G Noorani explains that Article 35A was a result of a solemn pact between the Union and the state and could not be unilaterally altered. Discussing the necessity of the provision in his statement in Lok Sabha, Nehru said, “So the present Government of Kashmir is very anxious to preserve that right because they are afraid, and I think rightly afraid, that Kashmir would be overrun by people whose sale qualification might be the possession of too much money and nothing else, who might buy up, and get the delectable places… So far as we are concerned, I agree that under Article 19, clause (5), of our Constitution, we think it is clearly permissible both in regard to the existing law and any subsequent legislation.”

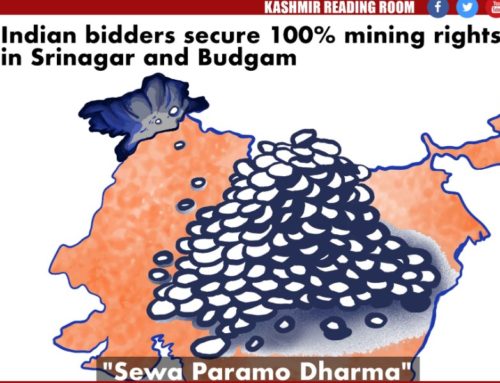

The de-operationalization of Article 370 in August 2019 has in turn led to a unilateral revocation of Article 35A by the Indian parliament. This means that the special rights ensured to the state population through the provision have also been annulled. In addition, on August 9, 2019, the J&K Reorganisation Act was passed through which state laws prohibiting transfer of land to non-state subjects were amended to permit such transfer. These amendments include – section 4 of J&K Alienation of Land Act, 1938, Section 20-A of Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950, section 4 of J&K Land Grants Act, 1960 and section 17 of J&K Agrarian Reforms Act, 1976. All of these provisions have been repealed by the 2019 Act. Now, the government of India has vast land resources in its control, which are now available for Indian corporate players to buy, along with the land of the peasants.

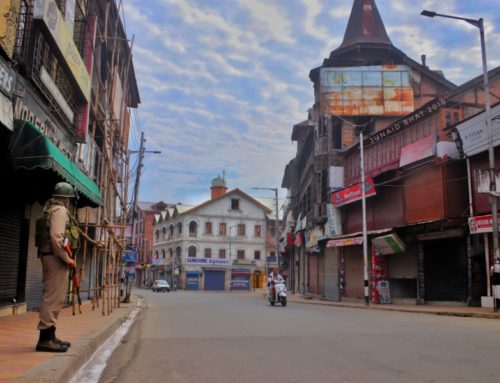

In addition to these legal changes, administrative decisions have been made at aggressive speed to clear forest lands and create land banks for ‘developmental projects’. Between August and October 2019, the Forest Advisory Committee of J&K has cleared a record 125 projects involving diversion of 271 acres of forest land for development projects. In February 2020, ahead of the global investor’s summit which was supposed to be held in J&K, an area of 60,000 kanals (7,500 acres) of the state land was identified and earmarked for industrial development. These decisions have been made in absence of an elected government in the state and in contravention of the procedure laid down under the J&K (Conservation) Act, 1997.

Land grab is not a new phenomenon in J&K. According to government records, the Indian military has grabbed 53,353 hectares of land in Kashmir under the guise of ‘national security’. In early 2018, former Chief Minister of J&K, Mehbooba Mufti informed the Legislative Assembly that 51,116 kanals of State land in Jammu and 3,79,817 kanals of land in Kashmir were under the unauthorised occupation of the India armed forces. Nabi and Ye argue that the occupation of agricultural land, forest land, state land and private buildings have led to dispossession, depeasantization and loss of livelihood for the peasant classes of Kashmir.

The Indian state has always employed the ‘development discourse’ to justify its arbitrary actions and interference with the governance of the state. Under the garb of ‘developmentalism’ and ‘welfarism’ India is furthering its agenda of land grab and colonization of resources to dispossess and disenfranchise Kashmiris at an alarming speed.

References:

- Dreze, J (9 August 2019). ‘Economist Jean Dreaze: Article 370 helped reduce poverty in Jammu and Kashmir’. National Herald. Retrieved from https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/india/economist-jean-dreze-jandk-more-developed-than-gujarat-special-status-helped-reducing-poverty.

- Ibid.

- Drabu, H. A (8 August 2019). ‘Was special status a development dampener in J&K?’. Live Mint. Retrieved fromhttps://www.livemint.com/opinion/columns/opinion-was-special-status-a-development-dampener-in-j-k-1565248797810.html.

- Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly Debate, Part I, Vol. I (1951-1955).

- Moza, M (1985). Agrarian Relations In J&K: A Case Study of Two Districts. Jawaharlal Nehru University: New Delhi

- Abdullah, S. M (1944). New Kashmir. Kashmir Bureau of Information: New Delhi.

- Zutshi, C (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Supra note 199.

- Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly Debate, Part I, Vol. I (1951-1955)

- Yengde, S., Teltumbde, A (2018). The Radical in Ambedkar Critical Reflections. New Delhi: Penguin Random House

- Bhatia, M (2014). ‘“Dalits” in J&K: Resistance and Collaboration in a Conflict Situation’. Asian Survey. 54, 5, pp. 941-965

- Brecher, M (1953). ‘Kashmir in Transition: Social Reform and the Political Furture’. SAGE Journals. 8, 2, pp. 104-112

- Mathew, G (2011). ‘Land Reforms: J&K Shows the Way’. Yojana. 55, pp. 24-26

- Iqbal, S (2018). Social Impact of State Development Policy in J&K: 1948 to 1988. University of Kashmir: Srinagar

- Supra note 199.

- Herring, R. J (1983). Land to the Tiller: The political economy of agrarian reform in south Asia. Yale University Press: Connecticut.

- Wani, A. A (2019). What Happened to Governance in Kashmir? Oxford University Press: New Delhi.

- Saxena, K. B (2016). Re-setting the agenda of land reforms. In Trivedi, P. K. (Eds.), Land to the tiller: Revisiting the Unfinished Land Reforms Agenda (pp. xiii-xxiv). Land and Livelihood Activities Knowledge Hub: New Delhi.

- Ibid.

- Noorani, A. G (14 August 2015). ‘Article 35A is beyond challenge’. Greater Kashmir. Retrieved from https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/opinion/article-35a-is-beyond-challenge/

- Scroll (21 October 2019). ‘J&K: 125 projects cleared on forest land since August, only 97 approved last year’. Scroll. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/latest/941222/jammu-and-kashmir-125-projects-cleared-on-forest-land-since-august-only-97-approved-last-year

- Zargar, A (29 January 2020). ‘J&K Admin to Identify 7,500 Acres of State Land for Industrial Development’. Newsclick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/jk-admin-identify-7500-acres-state-land-industrial-development

- Nabi, P. G & Ye, J (2015). ‘Of Militarization, Counter-insurgency and Land Grabs in Kashmir’. Economic and Political Weekly. 46&47, pp. 58-64

- Wani, F (10 January 2018). ‘Over 4.30 lakh kanals of land in J&K under occupation of security forces’. The New Indian Express. Retrieved from https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2018/jan/10/over-430-lakh-kanals-of-land-in-jammu-and-kashmir-under-occupation-of-security-forces-1750088.html

- Nabi, P. G & Ye, J (2015). ‘Of Militarization, Counter-insurgency and Land Grabs in Kashmir’. Economic and Political Weekly. 46&47, pp. 58-64

About the Author: Shinzani Jain is a researcher and writer. She has authored two books – ‘Thin Dividing Line’ with Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and ‘The Black Hole’ with Ajit Abhyankar. She is currently working as a Researcher with Tricontinental Institute for Social Research.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.