Deification of Land and the State:

Industry-Military Complex in Kashmir1This paper draws from research conducted by the author as the principal researcher of a team formed to study the Amarnath Yatra. For more details on this issue please see the report “Amarnath Yatra: A Militarised Pilgrimage” by JKCCS and EQUATIONS released in April 2017.

By Swathi Seshadri

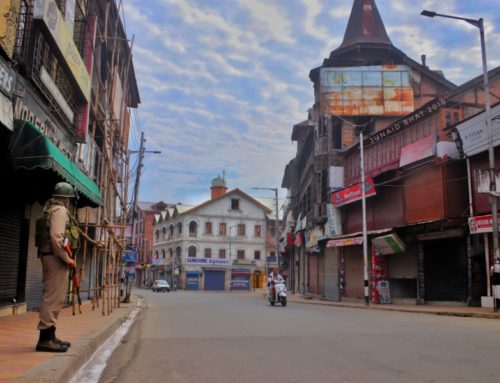

All over the world, tourism is popularly seen as a relatively harmless economic activity compared to dams and mines, in terms of its detrimental impacts on the environment and society. Tourism promotion and propaganda is centred around the joy that holidays bring to tourists, the income that it generates and the happy smiling faces of ‘hosts’ as they serve the ‘guests’2The tourism industry uses the terms “tourism destinations,” “hosts” and “guests.” Organisations who hold a political perspective of tourism contend that “tourism destinations” are the homes and backyards of people who live in villages, towns, mountain and coastal regions etc. which have been promoted by the tourism industry. The tourism industry views communities who live in these regions with lives, livelihoods and rights as mere “hosts.” And tourism industry’s “guests” are tourists who consume what the industry sells to them..While it does create some employment opportunities and income, it is not as innocent an activity as the industry would like us to believe. Like anywhere else, in the Kashmir valley too, tourism does generate some income in cities and towns like Srinagar, Pahalgam, Sonamarg, Gulmarg, etc. and is important for those who depend on it. However, viewed from a political-economic perspective, tourism in the valley takes on a completely different purpose where it is not merely an economic activity but a political tool used to show the world that everything is ‘normal’. In 2015, the then Union Minister of Tourism made the State’s intent clear when he said “We will combat terrorism with tourism in Jammu & Kashmir.”3ENS, (6 April 2015). ‘Union minister links terrorism, tourism; J&K govt not pleased’. The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/union-minister-links-terrorism-tourism-jk-govt-not-pleased/ In conflict areas, religious tourism in particular has been used as a political tool by the State to claim a historical right over the land. In Kashmir, the Amarnath Yatra has been a weapon to claim the land and ensure a steady stream of devotees from India into Kashmir. This paper looks at dynamics of land, economy and religious tourism in Kashmir and its role in the nationalism project of the Indian State.

Conflict regions and religious tourism

One of the most documented cases of the role of religious tourism in conflict areas is Jerusalem. Studies on religious tourism have used two approaches to understand the resultant dynamics that emerge. One school of thought led by the symbolic anthropologist Victor Turner believes that religious tourism causes “a relational equality of full unmediated communication, even communion” with other individuals, “which combines the qualities of lowliness, sacredness, homogeneity, and comradeship”4Badone, El and Roseman, S. R (Eds.) (2004). Intersecting Journeys: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage and Tourism. University of Illinois Press: Urbana, Chicago and Springfield. – understood as Communitas. He argued that often managers of pilgrimages seek this sense of communitas to communicate universalism of the pilgrimage and religion.5Di, G and Michael A. (2011). ‘Pilgrimage: Communitas and contestation, unity and difference – An introduction. Tourism: An International’. Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol. 59, No. 3. The Haj pilgrimage could be an example of this where according to the custom, all who perform the pilgrimage are equal and need to undertake the pilgrimage accordingly. On the contrary, British anthropologists John Eade and Michael Sall (1991) argue that each pilgrimage has a cultural, social and historical context, within which they should be analysed. They argue that pilgrimages are actually sites of contestation of discourses, with different groups – for example, those managing the pilgrimage, tourists, and people living in the region – viewing and perceiving the pilgrimage differently as the sites would hold different meaning to different sets of actors.5 It is in the context of the second perspective that certain sites of religious tourism become a maelstrom, with the religious beliefs of the dominant community becoming the universal truth. A poignant example of this contestation is Jerusalem, which is the principal pilgrimage site for Judaism as well as important to Islam (after Mecca and Madina).

Religious tourism in Kashmir: Orchestrating history

People of Kashmir have been in conflict with the Indian state since its formation in 1947. The Amarnath Yatra in Kashmir was the first experiment by the State to use religious tourism to push a political agenda. In this section we will see how three Yatras have been used to deify land and stake claim to it. First the Amarnath Yatra, which has been politicised since the 1990s, coinciding with the renewed struggle for freedom in the valley. A Yatra to Buddha Amarnath began in 2005 and is well on its way to being institutionalised. The Kousar Nag Yatra, a recent one, was initiated in 2009. This will enable us to see how systematically the Yatra is orchestrated to serve the nationalist purpose. Apart from these, Machail Yatra and Kailash Kund Yatra located in the hill districts of Jammu serve the purpose of ‘Hinduising’ Muslim dominated regions of Jammu. The Sindhu Darshan Yatra in Ladakh politicises religion in Buddhism-dominated Ladakh where it has been used to further the political interests of right wing organisations and parties.

Figure 1: Some important religious tourism sites in Jammu & Kashmir

Amarnath Cave

Every year, lakhs of people, mostly Shaivites from India travel to the Amarnath cave in Kashmir during the Shravan month of the Hindu calendar to pay obeisance to an ice stalagmite, which is believed to be an embodiment of the Hindu deity, Shiva. The Cave holds no importance to Kashmiri Pandits, and the current day rituals and beliefs of the Amarnath Yatra are only as old as 150–160 years.6In 1808, regions that were eventually ruled by Dogras came under Sikh rule. Maharaja Ranjit Singh bestowed Governorship on Gulab Singh, the head of the Dogras. With the purchase of Kashmir, the Dogras became rulers of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. This was resisted by the Muslims of Kashmir. In an attempt to establish their legitimacy and supremacy over Kashmir, the Dogras systematically planted markers of their form of Hinduism across the valley. For more details on this read: Rai, Mridu. (2004). Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. The Yatra first received state patronage around the 1850s under the Dogra kings7In 1986 after the British defeated the Sikhs, they sold Kashmir to the Dogra kings. It is believed that the Yatra first received state patronage after this. Just four years after the Dogra kings set up the Dharmarth to manage religious institutions, Buta Mallik ‘discovered’ the cave. Institutionalising a Yatra to the Cave, was interpreted as one way for Hindu kings to establish an ancient legitimacy on their Muslim subjects and their lands. It appears that this Yatra has had political compulsions even in the past. and again during the mid 1990s. The Amarnath Yatra is a well-orchestrated event involving multiple institutions from the State government, with security being coordinated by the Indian government. In 2001, the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB) was set up to coordinate the Yatra. Unlike other shrine boards where the District Commissioner is the Chairperson, the Chairperson of this Board is the Governor of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K). The Governor being a representative of the Union government makes the Board operate like a State within the State.8The use of ‘State’ in this paper refers to the State as defined by Max Weber: A state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. While ‘state’ refers to the administrative unit of Jammu & Kashmir. The district administration of Anantnag and Ganderbal are involved and preoccupied with the Yatra, while its commitment to the people living in these districts are abandoned. The Yatra is conducted under the shadow of the armed forces. While we do not have access to exact numbers, in addition to the massive presence of the armed forces in the valley, about 30,000 personnel are deployed along the route.9JKCCS & EQUATIONS (2017). ‘Amarnath Yatra: A Militarised Pilgrimage’. Bangalore Under the garb of acquiring land for the Yatra, attempts have been made since 2004 to usurp land to set up permanent infrastructure like offices, accommodation for yatris, toilets, etc. along the Yatra route, and for a township, to be named Amarnath Nagar. In 2004, the CEO of SASB initiated a process to acquire forest land to set up infrastructure for the Amarnath Yatra,10Choudhary, Zafar. (2008). Dangerous Politics Around 39 Acres of Land, Epilogue Volume 2, Issue 7. which was first granted by the Forest Secretary but was eventually revoked. Between 2005 and 2008 attempts to acquire land continued. People of the valley perceived the land transfer and the permanent structures as a renewed cultural and political onslaught on the region. It is another way for the people of the valley to be dispossessed of their land and natural resources, changing the demographics of the valley, and along with the presence of the military, another form of colonisation of Kashmir. Widespread protests across the valley resulted in cancellation of the land transfer but not before an economic blockade and killing of 61 civilians by the armed forces. In August 2012, there was once again news that a road to the cave was being constructed and other infrastructure along the route was being installed. In 2016, proposals to build a series of tunnels from Chandanwari to Panchtarni and then to Baltal, which would further connect to the tunnel at Zojila Pass, one of whose exits would be barely a few kilometers from the cave, were reported. Local economies do not particularly benefit from the Yatra as it clashes with the regular tourism season. According to the hotel, resort and shop owners in Pahalgam and Sonamarg, the Yatra, in fact, has a detrimental impact on it. Tourists do not prefer to visit the valley during the Yatra season due to large presence of armed forces, regular frisking of person and property, traffic jams and large crowds in the region. Tent, shop, pony owners and head load bearers are not particularly benefited since prices are fixed by the government without any consultation with the workers. Langar organisations11Langars are community kitchens which serve free food to the yatris located in Punjab, Delhi, Haryana, UP, Jammu etc. stand to gain as they raise large amounts of money for community kitchens.12There is no transparency in the finances of these organisations and a senior SASB official has admitted to this. Please see ‘Amarnath Yatra: A Militarised Pilgrimage’. JKCCS & EQUATIONS (2017). The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce is also kept out of decision making linked to the Yatra, limiting the involvement of its constituent members.

Buddha Amarnath, Poonch

The Buddha Amarnath temple is located in the Poonch district near the India-Pakistan border. Socio-religious organisations claim that this is a temple of a snow crystal linga and is therefore also colloquially referred to as Baba Chattani. The Bajrang Dal started organising a Yatra to this temple in 2005.13Jagran (27 August 2015). ‘Buddha Amarnath ke shradhalu utsahit’. Jagran News. Retrieved from http://www.jagran.com/jammu-and-kashmir/rajouri-12793666.html. Like the Amarnath Yatra, this is also conducted in August, during the month of Shravan. The Yatra, initially for 2-3 days, is now conducted for 15 days. Unlike the Amarnath cave, this temple has access by road and is open throughout the year. According to Baba Amarnath and Buddha Amarnath Yatri Niyas, 2,00,000-3,00,000 people visit the temple every year, of which 50,000-80,000 visit during the month of August. Several Amarnath Yatra tour operators offer a visit to Buddha Amarnath for free. As in the case of the Amarnath Yatra, only travel expenses are borne by the yatris, with food and stay taken care of by NGOs. The Yatri Niyas claim that “it is religion that takes people to such far-flung places like Buddha Amarnath and which creates a bonding for the religion across the country.”

Kousar Nag, Kulgam

Kousar Nag is a high altitude lake situated at a height of 12,000 feet. Local people believe that this is an old route used by ‘Gujjar Bakkarwals’ who also held the lake as sacred. Legend says that the Gujjars would stop here and sacrifice a goat, whose head would be thrown in the lake, which if sunk, meant that they were safe to move onward. Kashmiri Pandit organisations, like the All Parties Migrant Coordination Committee claim that a Yatra was conducted on Nag Panchami during the month of Shravan. An annual visit to the lake has been going on since 2009. There were concerted efforts in 2014 to mobilise people to participate in the Yatra, in an attempt for the Kashmiri Pandit community to lay claim to the lake. What was earlier a day’s visit by a few hundred people, was planned to be conducted as a 6-day Yatra from July 28 to August 2, 2014. More problematic was the support that the district administration of Reasi and Kulgam offered to this call – through logistical support including erecting sign boards – diverting yatris on Vaishno Devi pilgrimage to Reasi where the Yatra was to embark,14Wani, F (1 August 2014). ‘Kashmiri Pandits’ Kousar Yatra Kicks up Controversy’. The New Indian Express. Retrieved from http://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/Kashmiri-Pandits%E2%80%99-Kousar-Yatra-Kicks-up-Controversy/2014/08/01/article235 with accommodation at their Kongwattan Base Camp. What has been unfolding there is uncannily similar to the way the Amarnath Yatra had changed over the years – escalation of the Yatra in a militarised Hindutva manner. Kousar Nag Bachao Front (KBF), stopped the progress of the pilgrims at Kakran. The entire Valley saw protests akin to those during the Amarnath land row in 2008. While the Yatra was discontinued in 2014, media reports in 2015 suggested that the Yatra was being conducted silently.15Raafi, M (18 August 2018). ‘Silently, Kousar Nag Yatra Takes Off’. Kashmir Life. Retrieved from http://www.kashmirlife.net/silently-kousar-nagyatra-takes-off-83663/ in December 2015. According to VHP Vice-President of Jammu, conducting the Yatra silently without drawing attention is a strategy – he said: “once the Yatra is conducted regularly, after about 10–15 years, the younger generation would be made to believe that this was an ancient Yatra and that this new generation would keep the Yatra alive, thus lodging itself in the memories of the coming generations.”16JKCCS & EQUATIONS (2017). ‘Amarnath Yatra: A Militarised Pilgrimage’. Bangalore.

Religious Tourism during COVID 19

On April 22, a day before the beginning of the month of Ramzan, the Anjuman Auqaf Jama Masjid, Srinagar in a statement said:

“In view of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Anjuman Auqaf Jamia Masjid Srinagar, keeping in view the strict medical advisories of maintaining social distance by health experts will continue with the suspension of Friday congregations and Taraweeh prayers in Jamia Masjid, till the situation returns to normal, In Sha Allah.”17ONS (22 April 2020). ‘No Friday, Taraweeh Prayers In Jamia Masjid: Anjuman’. Kashmir Observor. Retrieved from https://kashmirobserver.net/2020/04/22/no-friday-taraweeh-prayers-in-jamia-masjid-anjuman/

On the same day, the SASB issued a press statement cancelling the Amarnath Yatra since the Yatra passes through 77 COVID-19 Red Zones. Later on the same day, in a U-turn, the Lt. Governor in a fresh statement said: “Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic situation being dynamic, an appropriate decision can be taken on organising the (Amarnath) Yatra on reviewing the situation in the coming future”.18Dey, S (22 April 2020). ‘Amarnath Yatra U-Turn: Press Note Cancelling Pilgrimage Withdrawn’. NDTV. Retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/amarnath-yatra-2020-cancelled-due-to-coronavirus-pandemic-2216443 On June 6, the SASB announced that the Yatra would be conducted for 15 days, from July 21 to August 3, from the Baltal route.19Livemint (6 June 2020). ‘Amarnath Yatra 2020 to begin on July 21 till August 3’. Livemint. Retrieved from https://www.livemint.com/news/india/amarnath-yatra-2020-to-begin-on-july-21-till-august-3-all-details-here-11591418460889.html In July, the SASB announced that 1000 yatris by helicopter and 500 yatris by foot would be allowed per day.20Khajuria, R. K (7 June 2020). ‘Amarnath Yatra: 1,000 pilgrims on helicopters, 500 on foot to be allowed per day via Baltal track this year’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/amarnath-yatra-1000-pilgrims-on-helicopters-500-on-foot-to-be-allowed-per-day-via-baltal-track-this-year/story-THuiDktB0jUafuhVax4tSI.html According to a JKCCS & EQUATIONS study, service providers present on the route are 1.5 to 2 times the number of yatris. This would take the total human presence on the route to 3750 to 4500 people per day, which over the 12 days would be 45,000 – 54,000 people. Important to note that on April 22 the total COVID-19 cases in Kashmir was 400, which rose to 10,153 by July 13. Compare the silence on the Yatra with the backlash, hate an ostracisation of the muslim community in the wake of what came to be popularly called ‘Tablighi Virus’, ‘Corona Jihad’, and ‘Mulism Virus’, when approximately 8,000 people visited the headquarters of the Tablighi Jamaat in Delhi in the beginning of March when the total cases in India less than 300! The Pratham Pooja (first pooja) for the Amarnath Yatra 2020 was conducted on June 5 as per schedule in the presence of the Lt. General of Jammu & Kashmir. The SASB also announced that the morning and evening aarti would be telecast live on Doordarshan everyday from June 5 till August 3. On July 13, the Supreme Court dismissed a case filed by Shri Amarnath Barfani Langars Organisation, which sought to restrict the access of general public and yatris in view of COVID-19. The petitioner argued that allowing the Yatra violates the June 29, 2020 guidelines issued by the Union Home Ministry under the Disaster Management Act, 2005. The Court evoked separation of powers and said, “we cannot enter into the arena of local and district administration.”21Tripathi, A (13 July 2020). ‘Supreme Court refuses to consider plea for restricting Shri Amarnath Yatra 2020’., Deccan Herald. Retrieved from https://www.deccanherald.com/national/supreme-court-refuses-to-consider-plea-for-restricting-shri-amarnath-yatra-2020-860667.html Incidentally, in 2012 Justice Swatanter Kumar had filed a Suo Motu Writ Petition under which a Special High Powered Committee was constituted and in which case a detailed judgement on several aspects of the Yatra was passed.22Suo Motu Writ Petition (Civil) No. 284 of 2012 Furthermore, on July 13, a lockdown was imposed in several parts of Kashmir, and orders were passed for strict punishment under the Disaster Management Act, 2005. It appears that there is a differential treatment and policy for Kashmiris and Indian yatris.

State-industry-military complex

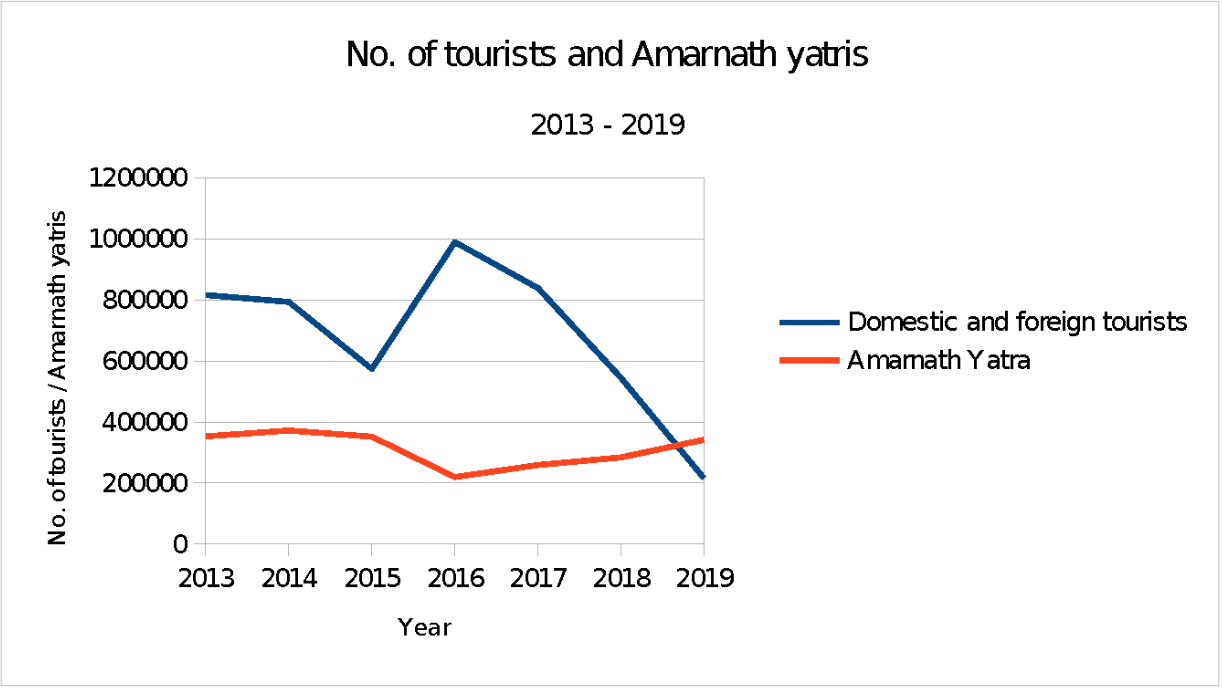

On the one hand, the government and tourism industry talk about the need to increase tourism in the valley while on the other, the state does not ensure the necessary conditions for tourism to prosper. Since Article 370 was amended a few days before the end of the Yatra, it did not have a significant impact on it. However, the tourist season in 2019 was severely affected. The internet is the backbone of the tourism industry anywhere in the world. Despite there being an interest among potential tourists to visit Kashmir, the internet shut down has made it impossible for houseboat and hotel owners to connect to them.23Ali, S, Bhat, A. H and Toogo, H. J (14 March 2020). ‘A Strange ‘Normalcy’ is Breaking the Bones of Kashmir’s Tourism’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/rights/watch-kashmir-tourism-normalcy According to the response to an RTI filed by The Wire, Kashmir saw a 71% decline in tourism revenue.24Bhat, M and Choudhury, C (26 January 2020). ‘Number of Tourists in Kashmir Down by 86% in August-December 2019: RTI’. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/government/kashmir-tourism-article-370-rti With the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Kashmir is facing a double lockdown and the tourism industry has missed two continuous tourism cycles. The graph below shows that the number of secular domestic and foreign tourists visiting the Valley has steadily decreased since 2016, while the number of Amarnath Yatris has remained relatively constant. In June and July, Kashmir received a steady flow of secular tourists which was 27% higher than the same period in the previous year.25Pandit, S (9 December 2019). ‘87% dip in domestic tourists to Kashmir since August’. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/87-dip-in-domestic-tourists-to-kashmir-since-august/articleshow/72430195.cms Between August and December 2019, Kashmir saw an 87% fall in tourists.26Chowdhury, A (19 February 2020). ‘No sign of revival for Kashmir tourism ahead of spring season’. Economic Times. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/no-sign-of-revival-for-kashmir-tourism-ahead-of-spring-season/articleshow/74215641.cms

According to the 2016 Economic Survey, religious tourism does not contribute to the local economy in any significant way since religious tourists do not spend on luxury tours, spend very few days in the valley, stay at budget accommodations, eat in community kitchens and do not tend to purchase souvenirs.27Economic Survey, 2016, Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Jammu & Kashmir The aviation industry, helicopter companies and tour operators where the majority of the yatris come from, in contrast, stand to gain the most from the Yatra. The fall in the number of domestic and foreign tourists, and the income generating sector in tourism has had a significant impact on the people. On the other hand, since the state organises everything necessary for the Yatra and is not dependent on the industry, neither the conflict in the region nor the pandemic has had any impact on it. Another example of the State (military) – industry nexus is the border tour buses that operated in 2016 that goes through sites such as Ranbireshwar Temple, Mubarak Mandi, Balidaan Stambh, Suchetgarh Border.28State Times (2 July 2016. ‘Priya Sethi flags off border tour buses for Amarnath Yatris’. State Times. Retrieved from http://news.statetimes.in/priya-sethi-flags-off-border-tour-buses-amarnath-yatris/ in July 2016. Diversion of forest land to the SASB, Amarnath Yatra infrastructure and Amarnath Nagar proposals are also examples of this partnership. More recently, there has been a surge in ‘re-discovery’ of pilgrimage sites. In 2013, the government compiled a list of 454 Hindu religious places and shrines.29See website of Divisional Commissioner Kashmir, Jammu & Kashmir: http://kashmirdivision.nic.in/WebPages/HinduShrines/hindushrines.html It appears that no attempts have been made to similarly identify Muslim and Buddhist shrines. A new trend witnessed in Kashmir is to identify sites of religious importance for Kashmiri Pandits, following which mass events are organised around them with the support of socio- religious organisations. It appears that this strategy is being adopted in the context of the 2016 Maha Kumbh at Saidipora, Ganderbal and the proposed but contentious yatra to a cave in Beerwah, believed to be linked to Abhinav Gupta. In both instances, Kashmiri Pandits are at the forefront, supported by socio-religious organisations, some of whom have also been instrumental in furthering the Amarnath Yatra. In the case of Amarnath, it was not just that the Board was set up to ensure State patronage, but this was actually only a front, and a premise for the Indian State to deploy its real might – its armed forces. If the purpose of the Yatra, as started by the Dogras, was to stifle dissent among the Kashmiris for being forced to accept them as kings, the Yatra in the post-1990s phase was infused with a nationalist agenda. People in India were mobilised to participate in the Yatra and show their loyalty to the country. Thus, religiosity of the Yatra was converted to a call for national pride as is evinced by the following quote from a Press Information Bureau release in 1997:

“Faith can move mountains, so goes an old adage. With a little variation to the saying, it is hoped that the yearning for Moksha (salvation) can move the devotees to the challenging heights of Kashmir. This will also be a befitting gesture of solidarity with our valiant soldiers who have been fighting the enemy to defend our borders.”30Press Information Bureau (1999). ‘Amarnath Yatra – 99 Acid Test of Devotion’. Retrieved from http://pib.nic.in/feature/fe0799/f1507992.html

Earlier in 1996, the Bajrang Dal had given a ‘Chalo Amarnath’ call all over India and were able to mobilise more than 50,000 people, with 21,000 being youth members of the organisation.31http://organiser.org/archives/historic/dynamic/modulese098.html?name=Content&pa=showpage&pid=36&page=16.

Once the sanctity of a space is secured, the next step is for the government to take upon itself the responsibility of providing amenities for the yatris, which means diversion of state resources to the yatra, but more importantly usurping land which are traditionally public commons. In January 2015, the then Union Minister for Tourism, Mr. Mahesh Sharma said, “Aksai Chin mein agar koi dharmik sthal hota to chin ki himmat nehin hoti aur aksai chin Bharat seema ki suraksha karne ki zaroorat nehin hoti“ (If there was a religious centre in Aksai Chin, China would not have dared and there would have been no need for border security). “Declare a pilgrimage centre in Aksai Chin. It will take care of the security issue. This is a part of our religious thought.” He also reported to have said that “religious places like Vaishnodevi and Amarnath ‘protect the borders’.”32Dash, D (22 January 2015). ‘A ‘religious’ centre in Aksai Chin would have scared away Chinese: Tourism Minister’. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/A-religious-centre-in-Aksai-Chin-would-have-scared-away-Chinese-Tourism-minister/articleshow/45973444.cms Deification of land appears to be a well thought out strategy to lay claim to the lands of Kashmir.

About the Author: Swathi Seshadri is a researcher and activist based in Bangalore. Her association with issues in Kashmir began in 2014 with her work on the Amarnath Yatra and subsequently through fact finding teams she was a part of in 2016 and 2019.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here. This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.