Article 370: From erosion to cremation

Mihir Desai and Saranga Ugalmugle

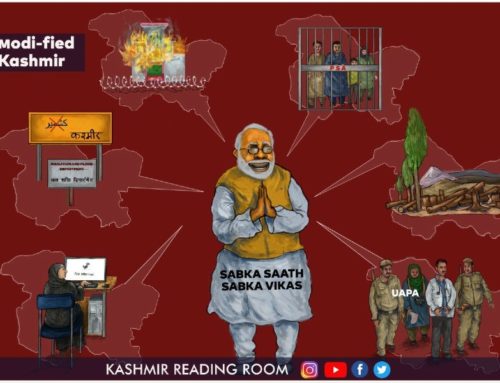

August 5, 2019 marks the cremation of the Instrument of Accession of the erstwhile princely state of Jammu & Kashmir(J&K) and the subsequent Article 370 of the Constitution of India. The Indian government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) finally fulfilled its long due agenda of ‘scrapping’ Article 370 and perpetuating its grand plan of complete integration of territory of J&K with India, one step closer to realising its ideal of ‘Akhand Bharat’.

Article 370 of the Constitution of India was the link between India and Kashmir. It reflected the commitment of the Indian people to the people of Kashmir- it was an agreement for Kashmir to have semi-autonomy within India. This followed from the Instrument of Accession(IOA), signed in October 1947, and the protracted negotiations between India and representatives of Kashmir. Article 370 provided for special provisions for J&K, which were as follows:

-

- It exempted J&K from provisions of the Constitution of India, which apply to all other states of India. Instead, Jammu & Kashmir were to have its own Constitution.

- The Indian Parliament’s legislative powers over the State are restricted to subjects of defence, foreign affairs, and communication. The President has the power to extend to the State other provisions of the Constitution ‘if they are related to the matters specified in the Instrument of Accession’ with the ‘consultation’ with the State Government.

- However, if ‘other constitutional provisions’ or union powers were to be extended to the State of J&K, the prior ‘concurrence’ of the State Government was required.

- This concurrence was strictly provisional since it has to be ratified by the State’s Constituent Assembly as provided under Article 370 (2).

- The State Government’s authority to give concurrence was to last till the State Constituent Assembly was convened. The President’s power to extend provisions of the Constitution of India to the State of J&K was to end once the State’s Constituent Assembly drafted and finalized the State’s Constitution.

- The President has the power under Article 370(3) to make orders abrogating or amending Article 370. Though, a ‘recommendation’ by the State’s Constituent Assembly ‘shall be necessary before the President issues such a notification’.

The Constitution of the erstwhile State of J&K was adopted on November 17, 1956 and came into force on January 1, 1957. The Constituent Assembly was thereafter dissolved on January 26, 1957.

The IOA, in late October 1947, was signed hurriedly with the specific condition of Indian troops coming in defence of the kingdom of Maharaja who was faced with an armed rebellion and invasion from Pakistani tribesmen in different parts of his kingdom. It is argued that this IOA between Maharaja Hari Singh of J&K and Governor-General Mountbatten of the Dominion of India, as it then was, is an agreement with binding legal obligation between two sovereigns. The two distinct yet equally situated contracting parties agreed on a compromise on the sharing of legislative powers. The political and constitutional history of India and the State of J&K suggests that there was a partial surrender of the sovereignty of Kashmir to India in only 3 specific matters. As far as issues beyond defence, foreign affairs, and communication, the State of Jammu & Kashmir had retained its sovereignty. Clause 7 of the IOA, specifically states that “Nothing in this Instrument shall be deemed to commit me in any way to acceptance of any future Constitution of India or to fetter my discretion to enter into arrangements with the Government of India under any such future Constitution”. Subsequently, a White Paper on J&K was issued by the Government of India in 1948 which reiterated that “In accepting the accession, the Government of India made it clear that they would regard it as purely provisional until such time as the will of the people of the State could be ascertained”.

This further attained the force of law through Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. The basic provisions of the said Article are mentioned above. It then provided a legal basis for provisions like Article 35A, which was subsequently introduced to protect rights to property of people of Kashmir by ensuring that only state subjects with proof of permanent residency status are entitled to own land within its territory. Through Article 35A, non-permanent residents were also disallowed from being appointed in government services as well as from becoming members of the state legislature.

It is clear from the above history of the manner of integration of J&K into India that Article 370 was transitory, only in the sense that the right to decide permanently on the relation between India and J&K vested, in the final measure, in the Constituent Assembly of Kashmir through the Constitution of J&K. Without the sanction of the Constituent Assembly, no further changes could be made. The Constituent Assembly dissolved in 1957, and therefore there was no question of making any further changes to the relation between India and Kashmir by any other authority, including the President of India. Further, the relation between India and Kashmir as laid down in the Constitution of Kashmir in 1956 is part of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution and therefore cannot be changed except with the approval of the Constituent Assembly of Kashmir. Thus, the Constitutional relationship between India and Kashmir was frozen in time in 1957.

The first Presidential Order was executed on the very day that the Indian Constitution came into effect in January 1950. This Presidential Order called the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order 1950 was executed to apply the Constitution of India to J&K, under the terms stipulated in Article 370. The said order extended India’s legislative jurisdiction in J&K to 37 out of 100 subjects listed in the Union List of the Constitution of India, including those not related to ‘defence, foreign affairs, or communications’. Preventive detention, concerning defence, foreign affairs, and the security of India, which later went on to become the ‘lawless law’, was a subject on which the Indian legislature could legislate. Since the 1950s itself, India ignored the special status afforded to J&K and introduced a series of executive Presidential Orders of 1950 and 1954. The Indian Supreme Court almost religiously sanctioned and approved of these erosions of Article 370.

Supreme Court and Article 370

In the case of Prem Nath Kaul, the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court upheld the above position concerning the crucial role of the Constituent Assembly. In this case, the petitioner had challenged the authority of Prince Karan Singh to enact a legislation for the state. The five-judge bench upheld the Act and stated that “Constitution-makers attached great importance to the final decision of the Constituent Assembly, and the continuance of the exercise of powers conferred on the Parliament and the President by the relevant temporary provision of Article 370 (1) is made conditional on the final approval by the said Constituent Assembly in the said matters”.

An opposite interpretation was given by the Supreme Court in 1968, in the case of Sampat Prakash essentially holding that Presidential Powers to extend laws concerning all other items in the Union List of the Indian Constitution continued even after the J&K Constitution was made. Surprisingly, in arriving at this conclusion, the Supreme Court completely overlooked the Constitutional Bench judgment in Prem Nath. Thus, Sampath Prakash judgement triggered the transition of Article 370 from a temporary provision into a permanent mechanism for systematically eroding the provision, to extend Indian legislative jurisdiction over the J&K through a series of Presidential Orders superseding the limitations imposed by the IOA.

Thereafter, in the case of Puran Lal Lakhanpal, the Supreme Court, while deciding on the question of whether the power to make modifications through a Presidential Order under Article 370 was limited to making minor alterations, held that the term ‘modification’ must be considered in its ‘widest possible amplitude’. The five-judge Constitution Bench, decided that while applying any provision of the Indian Constitution to the State of Jammu and Kashmir, the President of India can use his/her power even to make a radical transformation to ‘extend’ the application of the provisions of the Indian Constitution.

This is how, over the decades, there has been a constant erosion of Article 370 by devious means through a large number of Presidential Orders made thereunder. Through these Presidential Orders, 94 of the 97 entries in the Union List were extended to J&K. Moreover, 260 of 395 of the Articles of the Constitution of India were also extended to the State. This was done through deceit and betrayal of the people of Kashmir either by getting the consent of puppet State Assemblies set up through rigged elections or the consent of the Governor during the many times when the Governor’s rule was imposed. In fact, all the Presidential Orders made after 1957 are unconstitutional since they are without the concurrence of the Constituent Assembly.

Article 370 has thus been hollowed completely by the various Presidential Orders and their legitimation through the Apex Court of India. The Supreme Court has allowed the Indian state to undermine the letter and spirit of Article 370 and the special status that is granted to the State of Jammu & Kashmir. The Supreme Court has not just been a bystander to this Constitutional mayhem but seems to have, in effect, endorsed it.

August 5, 2019

The Governor of J&K issued a proclamation on June 20, 2018 under Section 92 of the Constitution of J&K with the concurrence of the President of India, assuming to himself the functions of the Government and Legislature of the State. The State Assembly, initially kept in suspended animation, was eventually dissolved by the governor on November 21, 2018. The President of India issued a Proclamation under Article 356 of the Indian Constitution on December 19, 2018, imposing President’s Rule in J&K. It is pertinent to note that vide the said notification, the operation of the second proviso to Article 3 of the Constitution pertaining to Jammu and Kashmir was suspended, which later allowed conversion of the State to Union of Territory.

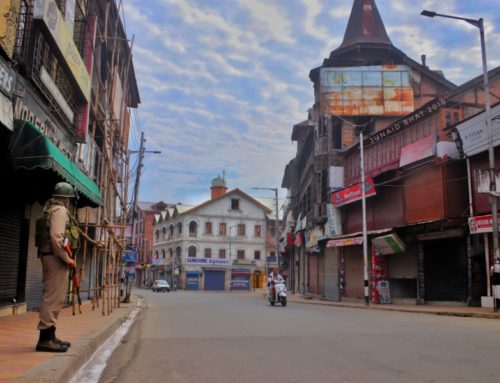

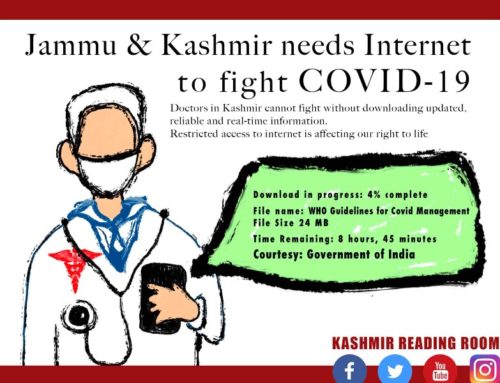

Subsequently, on January 5, 2019 the Union Cabinet approved the imposition of President’s Rule in J&K for a further period of six months under article 356(4) of the Constitution of India. The Presidential Rule was extended and continued to be in existence as the orders/Act of August 5 and 6 were passed. At midnight of August 4, 2019, all communication services in the territory of the erstwhile state of J&K were blocked and thousands of people, including former Chief Ministers and other previously elected representatives of the state were put under detention. On August 5, 2019, a Presidential Order, G.S.R.551(E) – The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019 was passed by the President of India allegedly in the exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of Article 370 of the Constitution. This order supersedes the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954 by which special status had been given to J&K. Besides, it extends the provisions of the entire Constitution of India to Jammu and Kashmir. It further amended Article 367 of the Constitution of India to read the term ‘Constituent Assembly’ in Article 370 as ‘State Legislative Assembly’.

The Rajya Sabha, on the same day ie. August 5, 2019 passed the Jammu and Kashmir (Reorganisation) Bill, 2019, unanimously. The Bill provides for the reorganization of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. It reorganizes the state of Jammu and Kashmir into (i) the Union Territory of J&K with a legislature, and (ii) the Union Territory of Ladakh without a legislature. The Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir will be administered by the President through an administrator appointed by him, known as the Lieutenant Governor. The Union Territory of Ladakh will be administered by the President, through a Lieutenant-Governor appointed by him.

On August 6, 2019, a Declaration, G.S.R.562 (E), was issued by the President under Article 370 (3) of the Constitution of India on August 6,2019. It read that,

“In exercise of powers conferred by clause (3) of Article 370 read with clause (1) of Article 370 of the Constitution of India, the President, on the recommendation of Parliament, is pleased to declare that, as from the 6th August 2019, all clauses of the said Article 370 shall cease to be operative except the following which shall read as follows, namely :

Article 370. All provisions of this Constitution, as amended from time to time, without any modifications or exceptions, shall apply to the State of Jammu and Kashmir notwithstanding anything contrary contained in Article 152 or Article 308 or any other article of this Constitution or any other provision of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir or any law, document, judgment, ordinance, order, by-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usage having the force of law in the territory of India, or any other instrument, treaty or agreement as envisaged under Article 363 or otherwise“.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir were neither consulted before such a drastic change in their relationship with India was introduced nor were they informed about it since no telecommunication, publication, and distribution was allowed in the State before and even after these impugned Orders/Act had been introduced. Both procedural and substantive safeguards provided in the Constitution of India were completely bypassed in introducing the said orders. The concurrence of the Constituent Assembly, as required, was not possible (since it has been dissolved) and the concurrence of the State Legislative Assembly was not sought (since it was deliberately suspended much before the said order was passed). In doing so, the Indian government has been cunning and deceitful.

Thus, with political treachery, Article 370 has not been done away with but has been completely hollowed out with the aforesaid actions of August 2019. While Article 370 had lost much of its significance over the decades, its symbolic importance cannot be denied. Till now, at least morally it was accepted that people of Kashmir had a special distinct and significant place within the Indian Constitution. The understanding was that Kashmir was for Kashmiris. While it was part of India it had special features arising out of the Constitutional arrangement and commitment to the people of Kashmir, which have now been destroyed. While the Congress and its puppet Governments began this slow process of betrayal, the final nail in the coffin was hammered in by the BJP Government which always declared that Article 370 should be abrogated. This was part of their Hindutva project and done with the object of teaching Muslims in India a lesson.

Soon after the August 2019, legislative decisions, multiple petitions were filed in the Supreme Court challenging the abrogation. The Supreme Court of India was called upon to decide on issues of limits of executive functioning and federalism. The supposed sentinel on qui vive is expected to help the throttled democracy to breathe by urgently putting a check on this undemocratic and unconstitutional move by the Indian government. Ideally, they should have decided on these matters by now. What could be more important for the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India than the survival of Constitutionalism and democracy? However, there has been a completely unjustified delay on part of the Supreme Court and the matters have kept on lingering. In fact, on September 30, during one of the hearings, the Supreme Court delayed the hearing of the matter, stating that, “We do not have time to hear so many matters. We have a Constitution Bench case (Ayodhya dispute)to hear.”

The only issue which has been decided and dangerously so is that there is no conflict between the judgments in Prem Nath and Sampat Prakash’s cases which have been discussed above. In Dr. Shah Faesal’s Case a Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court shockingly decided that there was no conflict between Prem Nath’s Case and Sampat Prakash’s Case. Not only this but through a tortuous process of wrong interpretation, it upheld the Sampat Prakash interpretation which sought to do away with the significance of the Kashmir Constitution and Constituent Assembly.

While Petitions challenging Article 370 are still pending, it is not certain when they will be decided and, in the meanwhile, the Central government is going full speed ahead to make these petitions infructuous.

With ‘special status’ gone…

The Jammu and Kashmir (Reorganisation) Act, under its Schedule Five, extends 106 Central legislations to the two new Union Territories. 164 out of the 330 State and Governor’s Acts continue to operate with 166 being repealed. Seven laws which are sought to be amended concern reservation for economically weaker sections as well as title and transfer of land.

Given the prior special status of J&K, there was a bar on non-locals leasing and renting of mineral blocks in the region. However, the auctions were opened for businessmen from outside of J&K, post-August 5. Following this, majority of mining and sand extraction contracts were secured by non-local contractors who have already started their operations without the requisite environment clearances.

The changes in land rights and domicile law are arguably the most pressing concerns arising out of the amendment of Article 370 and the subsequent Reorganisation Act. The Indian government extended domicile reservation to all government posts in Jammu and Kashmir in April 2020, during the COVID 19 lockdown. Thereafter, the J&K administration notified the Jammu and Kashmir Grant of Domicile Certificate (Procedure) Rules, 2020, which specify the conditions and the process to obtain the documents required for applying to jobs and avail other privileges restricted to residents. Reports suggest that 25,000 people have already been granted domicile certificates of which one is an IAS Officer from Bihar. These changes, though subject to legal challenge, are apprehended to be a mechanism for creating permanent demographic changes and further perpetuating the project of the homogenous identity of one integrated nation.

With no bars on the transfer of land to non-permanent residents and a ceiling on the transfer of state land to non-permanent residents removed; the path towards dismantling all the protections afforded to people of Kashmir, by whatever was remaining of Article 370 (before August 5, 2019), has been accelerated. The Supreme Court of India, if it so chooses, can put a stay on all these processes till the validity of the abrogation is decided. The Hon’ble Court could also, if it wills, decide the petitions pending before it with a sense of urgency. Though what remains to be seen is whether democracy, federalism, rule of law and constitutionalism are issues that merit such urgent attention by the Highest Court of Law in India.

References

- Government of India (26 October 1947). ‘Instrument of Accession of Jammu and Kashmir’. Retrieved from http://jklaw.nic.in/instrument_of_accession_of_jammu_and_kashmir_state.pdf

- Any reference to the State of Jammu and Kashmir should be construed as the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir; The erstwhile State has been reorganized to form two separate Union Territories of J&K and Ladakh.

- Government of India (1948). ‘White Paper on Jammu & Kashmir’. OCLC Number: 9440812, LCCN Number: 80915605

- The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1950. Retrieved from http://jklaw.nic.in/jk1950order.pdf

- Amnesty International (2019). ‘Tyrany of a ‘Lawless Law’. Amnesty International. Retrieved from https://amnesty.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Tyranny-of-A-Lawless-Law.pdf

- Prem Nath Kaul v. The State of Jammu and Kashmir, Supreme Court of India (2 March 1959), AIR 1959 SC 749.

- In that particular instance, reference was the Jammu and Kashmir Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950.

- Sampat Prakash v. State of Jammu and Kashmir & Anr., Supreme Court of India (10 October 1968) AIR 1970 SC 1118.

- Puranlal Lakhanpal vs The President Of India And Others, Supreme Court of India (30 March 1961), 1961 AIR 1519, 1962 SCR (1) 688.

- The Ayodhya dispute has been going on for more than 100 years. It is essentially a tussle for ownership by and between the Hindu and Muslim communities over a piece of land admeasuring 1500 square yards in the town of Ayodhya, in state of Uttar Pradesh. ‘Ayodhya Dispute: The complex legal history of India’s holy site’. BBC (9 November 2019). retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50065277; Ugalmugle, S (14 November 2019) ‘Balanced’ in favour of the Majority?’. Indie Journal. Retrieved from https://www.indiejournal.in/article/balanced-in-favour-of-the-majority.

- Dr. Shah Faesal and Ors. vs Union of India and Ors., Supreme Court of India (02 March 2020), 2020 SCC ONLINE 263.

- LiveLaw News Network (2 March 2020). ‘Article 370: No Need To Refer Pleas Challenging Repeal Of J&K Special Status To Larger Bench, Holds SC 5-Judge Bench’. LiveLaw.in. Retrieved from

https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/article-370-no-need-to-refer-pleas-challenging-repeal-of-jk-special-status-to-larger-bench-holds-sc-5-judge-bench-153350. - Varma, S (11 August 2019). ‘Land Grab, Political Disempowerment are Twin Pillars of J&K Changes’. NewsClick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/Jammu-Kashmir-Article-370-Revoked-Land-Grab-Political-Disempowerment-Modi-Government.

- Zargar, A (5 February 2020). ‘With Article 370 Gone, Locals Lose Majority Bids for Sand Extraction in Kashmir’. NewsClick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/Article-370-Gone-Locals-Lose-Majority-Sand-Extraction-Kashmir.

- Zargar, A (30 June 2020). ‘J&K: New Contractors Being Extraction on Mineral Blocks without Environmental Clearance’. NewsClick. Retreived from https://www.newsclick.in/Jammu-kashmir-new-contractors-begin-extraction-mineral-blocks-without-environmental-clearance.

- Newsclick Team (4 July 2020). ‘J&K: Mining Without Environmental Clearance. NewsClick. Retrieved from https://www.newsclick.in/jk-mining-without-environmental-clearance.

- HT Correspondent (19 May 2020). ‘J&K notifies domicile rules for jobs, other privileges’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/j-k-notifies-domicile-rules-for-jobs-other-privileges/story-tmHdlqrruRKUFoo5KWdHCP.html.

- Saman, L (26 June 2020). ‘IAS Officer among 25,000 people granted domicile certificates in J-K’. The Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/j-k/ias-officer-among-25-000-people-granted-domicile-certificates-in-j-k-104783.

- India Today Web Desk (15 August 2019). ‘PM Narendra Modi calls for one nation, one election in Independence Day speech’. India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-narendra-modi-one-nation-election-independence-day-speech-1580998-2019-08-15.

About the Author: Mihir Desai is a Senior Advocate in the High Court of Bombay and the Vice President of PUCL. He was a legal counsel to the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Kashmir.

Saranga Ugalmugle is an advocate in the High Court of Bombay. She is pursuing LLM from Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (2020-2021). Both the authors were part of an eleven member team that visited Kashmir in September, 2019.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.