Coming Together on one Platform

Jang-Vijay Singh

“When the Walls Came Down and the Windows Went Up”

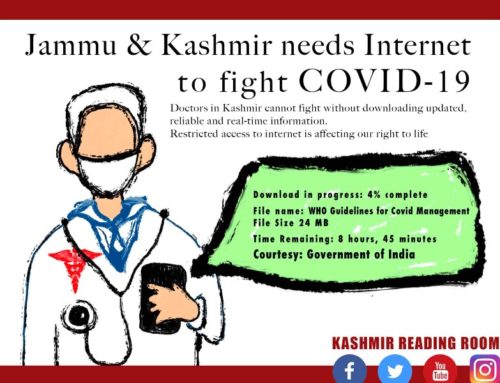

Alluding to the fall of the Berlin wall, Thomas Friedman in his book ‘The World is flat’ thought a lot of credit for bringing freedom to a large part of Eastern Europe beyond the iron curtain went to the rise of information and communication technology during that decade. The edifice of authoritarian regimes of that time was based on strict control of information. There is a reason most authoritarian regimes of that time persisted on heavy censorship – foreign newspapers and media, for instance, were heavily censored behind the iron curtain. As information and ideas slipped through the cracks, so did the cracks in the wall widen, and the wall fell.

Conflict is as normal as life – it is how we deal with it that distinguishes our civilisation. Most human beings don’t hold malice towards their fellow humans. This is not entirely true – as realists, we need to acknowledge that in a world governed by ‘might is right’, malice and aggression (and its associated characteristics like corruption, authoritarianism, oppression) might have paid. But it shouldn’t. And increasingly doesn’t. If we think clearly and pay attention. Both sets of examples can be found in the world from recent history and today and it is for us to observe and draw lessons (Why nations fail – The book’s title could be summed up in one phrase: greed and extractive institutions – violence and discord only serve these interests).

If there’s sincerity, there is no conflict that cannot be resolved by dialogue and communication. For many countries like East Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia), that era was like a wasted half of a century. Whatever views one might have of globalisation, information and communication is a necessity today as basic as electricity.

The lead up to August 5, 2019

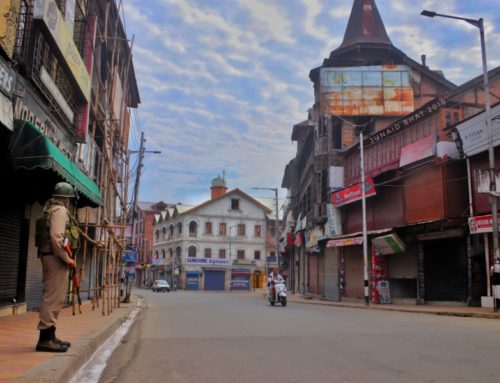

The year had a strange quality to it. Too many voices from India were taking an aggressive tone about Kashmir and its so-called ‘special status’ (the term itself might have been partly to blame – it was a negotiated federal arrangement within a union, but focus on the word ‘special’ seemed to trigger unwelcome views from random quarters who could have done better to focus on their own regions). And there was a strange quality in them – many of the most vocal proponents of revocation of this so-called ‘special status’ did not seem to have any reasoned arguments or originality. In online discussions on public or private Indian groups, one could perceive a scripted barrage of arguments to drown any counterargument aggressively – it was clear that discussion was pointless and merely exposed one as a target. The Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly had been suspended for more than a year – so the state had no democratic voice left, not even pretence of one.

July had an odd and sinister quality to it. Where else in the world are roads blocked to civilian traffic, to prioritise a pilgrimage? There are things that did not seem rational – it seemed as if events were engineered to cause the most discomfort to local civilians. Kashmiris have been known to go out of their way to accommodate visitors and pilgrims. But when there are constraints on highways and local resources, the sensible thing to do is to work with the locals. If I need to visit a Gurdwara across town, I might choose to drive at a sensible time of lower traffic, or I might choose to walk, or I might choose to pray at home or a nearby Gurdwara. These are rational choices we make depending on our surroundings and infrastructure.

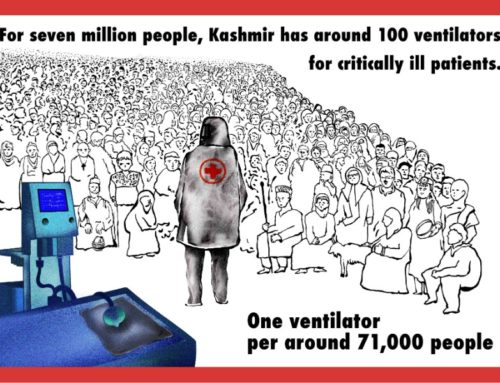

One of my goals for a long time had been to record interviews of elderly relatives who had seen the events of 1947 first hand. In the last few decades, their memories and testimonies were being lost one by one, as they aged and concluded their lives. Regardless of our political views today, recording their thoughts was significant. So, during the month of July, I got the chance to meet and record the first-hand memories of an elderly relative in my village. The end of my trip happened to be the last week of July by a sheer coincidence – rumours and news reports suggested further military build-up, so everyone knew something was about to happen. No one knew what. I must remain guarded in my words, but someone has to question why or how can a whole population of 7-8 million be subjected to such psychological torture? How can an administration advertise claims of ‘development’ on the one hand, and yet, create such extreme levels of uncertainty? There were reports of major roads and highways being blocked to civilians for days just so the vehicles of the armed forces could move.

As someone who identifies as Kashmiri Sikh (in the diaspora, but retaining a strong connection), I was asked to comment on these events from a Sikh perspective – but I can’t think of how this narrative could be any different from the perspective of any other citizen. That being said, there are issues and predicaments quite unique to Sikhs in the valley.

After 5 August 2019

On the 4th of August, a journalist friend working in London reached out to me and tried to get a comment from me. Rather than commenting myself, I offered to share contact numbers of some journalist friends based in Kashmir who had been vocal in their writings – documenting their experiences. A message I sent to a friend about this remained unread and unanswered. The Internet shutdown had started, and everyone was incommunicado. This was Kashmir, but to get an idea of what this might be like, one must imagine the whole populations of Norway, Denmark, or Scotland being subjected to such a blockade for months – all of these have a population similar to the province of Kashmir.

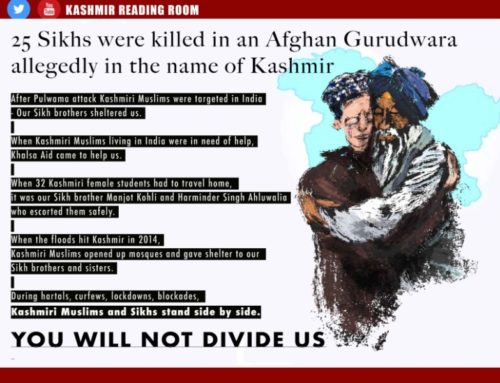

One could notice a marked change in the narrative around Kashmir after this day. There seemed to have been an almost overnight switch in the views that some people started expressing. Some Sikh friends stayed quiet, but I could notice a peculiar change in a few others. On the one hand, Sikhs of Kashmir, despite having suffered from the conflict themselves while being a non-party, have a deep sympathy with their Muslim neighbours, who numerically have been the largest sufferers of the conflict. On the other hand, Sikhs must work with every administration of the day for their daily existence – from public services to employment, which includes employment in police forces. Though Muslims have the same motivations, Sikhs as a minority group stand out.

There was a sudden glee in some sections of Kashmiri diaspora as well – the religious divide was visible and apparent – that frankly bordered on obscene considering the fact that the whole of Kashmir had been gagged – its newspapers shut, its internet and telecommunications blocked. There was an undeniably scripted quality to these narratives that could broadly be categorised into ‘development’, ‘women’s rights’, and ‘minority rights’ (the situation of Kashmir’s minorities being deliberately conflated with ‘Hindus’ in general – state’s permanent residency laws were presented as discriminatory towards minorities).

Dissenting voices in the diaspora who could speak were, of course, labelled quickly with the usual list of nouns. We were frequently gaslighted and questioned whether we even knew Kashmir firsthand (the implication being that Kashmiris were now fully compliant with Indian nationalism, and we were simply out of touch). The absurdity of this situation was that Kashmiris in Kashmir had no means of reaching out.

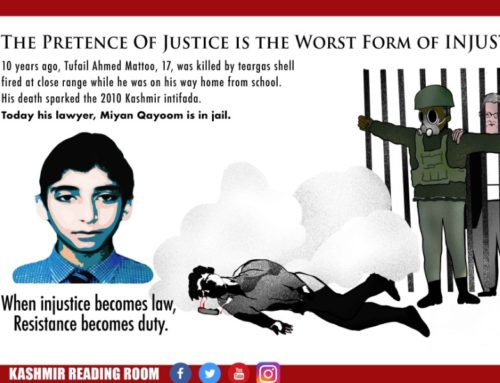

On such sensitive matters, it is unwise to lend credence to conspiracy theories or conjecture without a sound basis. The fact that investigations for events like Chitisinghpora had never reached a definitive conclusion and did not help. One was meant to accept either the state narrative (terrorists did it) or the alternative narrative (it was done by design to coincide with Clinton’s visit).

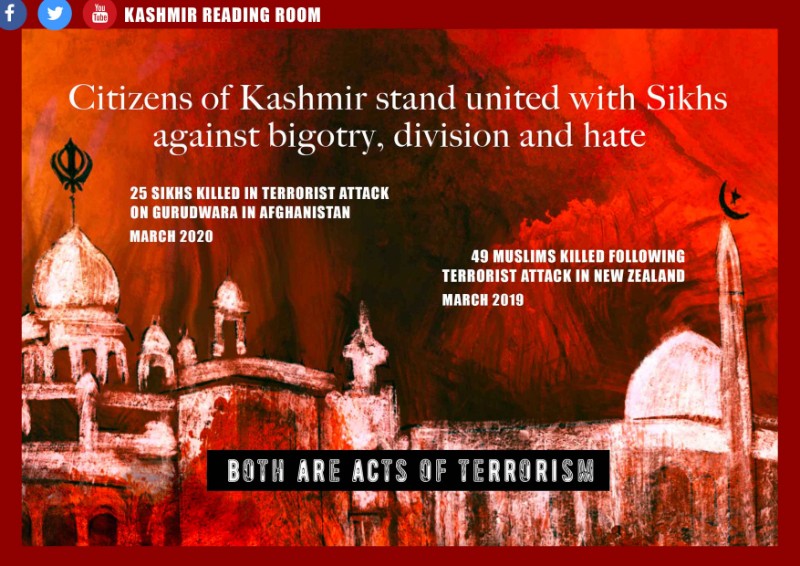

But for every major incident, it helps to analyse who the beneficiary of such an event might be. The terror attack in a Gurdwara in Afghanistan was claimed to be in retaliation for Kashmir. Our Kashmiri Muslim compatriots were quite rightly vocal about denouncing it and clearly that had nothing to do with them or Kashmir’s politics. However, as co-religionists of a group that has seen steady dwindling from a once thriving and patriotic Afghan Sikh community to a few families who till now steadfastly held on to their country, many Sikhs cannot shake off nagging doubts over their own future in Kashmir. Does it matter who really is to blame for even one odd terrorist act, when either way, you might be staring at a prospect of a future like them?

Then there are occasional voices who seem to appear out of nowhere to give communal/sectarian angle to everything from thefts, acts of vandalism (e.g. news reports of break-in and theft in a Kashmir Gurdwara, oddly coinciding with vandalism in a UK Gurdwara by a man reported to be of Pakistani origin and claiming to do it in retaliation for Kashmir), to more serious crimes like the targeting of a Sikh relative of a panchayat leader in Kashmir (and more recently a Kashmiri Pandit panchayat leader). Clearly, our foremost concern is that people must not lose their lives to violent attacks, but the sectarian labelling of all these events makes matters worse and, in all scenarios, it’s Kashmiris as a whole that stands to lose.

From my observation, such concerns are always balanced by views of other Sikhs who readily point out the harmony and cooperation with which local communities live within Kashmir and the sad fact that Mosques had also been targets of thefts in unrelated incidents. A prime example was during the floods, when people regardless of religion helped each other – sheltering each other in Gurdwaras and Mosques, ensuring the safety of tourists as well. And then, after the 5th of August 2019, Sikhs across India expressed solidarity with Kashmiris. This is how our religious values shine – those who seek to benefit by manufacturing religious conflict invariably have other more materialistic greeds.

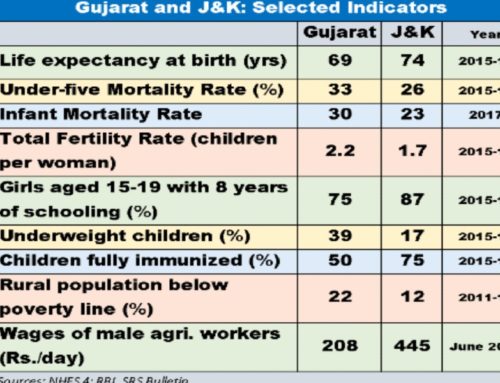

Finally, in the immediate aftermath of the revocation of nominal state autonomy, some Sikhs did have an expectation of finally gaining some representation (both politically, in elected bodies, and in government services, in the form of reservations). As far as one can tell, so far, they have been disillusioned on both aspects – as have all Kashmiris faced disillusionment for decades. We need to understand that only the people of J&K are in the best position to think of the best future for J&K, and the best interests are served when rights of all of its constituents are safeguarded – by sincere mutual dialog.

Sikhs of Kashmir

Our initiatives for engagement with the outer world can be meaningful when we start to recognise that the state of Jammu and Kashmir as a whole, and the province of Kashmir, have multiple internal stakeholders whose interests are intertwined in the interests of Kashmir (this is also true of the province of Jammu, of Ladakh, Gilgit-Baltistan, Poonch-Mirpur and other regions, but my discussion remains focused on Kashmir for now). This clearly does not mean denying the status or interests of any one group but ensuring that all stakeholders and their interests are taken into account. Like Kashmir’s other communities, majority Muslims and Hindus, Sikhs have had a historically significant role in Kashmir in all fields. Whether indigenous converts (Kashmir was one of the places regularly frequented by founder Gurus of Sikh faith) or settlers from within the last 300 years, Sikhs played a role in every aspect of Kashmir’s public life – from agriculture and horticulture to construction, transport, and education. For political reasons, during the Dogra era, Sikhs maintained a low-key existence far from urban centers and largely outside of positions of power at least till the early 1900s. The state transitioned to its brief era of democracy in 1947 after a deep trauma that remains a watershed moment in Sikhs’ existence in Kashmir. The tribal invasion of October 1947 remains ingrained on the Sikh psyche till today. The tragic aspect was that this happened even though there was no animosity between various communities who actually lived in Kashmir. The suddenness of this invasion can be ascertained from the fact that a mere ten days prior to the arrival of the first band of invaders, state officials had expressed neutrality and hopes of a Switzerland-like future for Jammu and Kashmir (people might doubt their sincerity and motivations, but at least they were on record on this). And yet, for a community who’s past and future lay with Kashmir had been uprooted from vast areas across the LOC – and nearly uprooted from deep within the valley from areas that invaders reached. The ray of hope was when the state transitioned to democracy and the first constituent assembly acknowledged the role of the state’s citizens in coming together in the face of that invasion – the conduct of Kashmiris in particular, was quite unlike people of the ‘plains’ who had turned on each other in deeply abhorrent ways.

It is important to recognise that the tribal invasion of Kashmir and the violence in Jammu leading are two separate events. Jammu is a province bordering Punjab – both sides of Punjab were ethnically cleansed of ‘the other’. When Kashmiri intellectuals highlight the Jammu massacre of Muslims, there has to be an equal recognition of the fact that areas across the LOC (parts of Poonch, Mirpur, Muzaffarabad) faced complete annihilation or exodus of their non-Muslim populations. Both these events deserve condemnation, and neither must be misrepresented as a consequence of the other. The influx of refugees with narratives of what they had faced on the other sides likely fed into a downward spiral of violence. The way these events are now presented to a less discerning audience has a bearing on community relations today and in the future. It might win momentary sympathy for one side, keeps us stagnated and divided – moreover, it allows outside powers to perpetually exploit this history for their own more sinister ends. A complex history that we within J&K need to take ownership of in an honest manner, is distilled down to one simple question: Hindu Rashtra, because ‘they’ invaded or Islamic Pakistan, because ‘Jammu massacre’.

It is important for people to imagine what an alternative future of Jammu and Kashmir might have been had there been no India-Pakistan partition on religious lines. If we go by the indigenous political activity within Kashmir, such as the tragic events of 1931, it was about transitioning from a feudal autocratic system to responsible government – a transition that happened all over the world, but without the terrible human cost that was inflicted on Kashmir.

During the period of state autonomy

We have to assess this from the situation prior to the armed conflict and after. While being important stakeholders in the present and future of Kashmir, like Kashmir’s other minority groups, Sikhs are not actually party to the conflict – whichever direction the future of Kashmir takes, they need to ultimately secure their future and rights as a minority group in cooperation with other stakeholders.

The conflict is presented as either an India-Pakistan conflict or a Hindu-Muslim one. This is clearly the agenda of powerful parties involved and one wonders if they simply collude together while keeping up this presence of animosity, simply to shut down the voice of Jammu and Kashmir. The key stakeholders of the conflict, people of Kashmir, struggle to get even mentioned (such as the advice often received from western powers around how “India and Pakistan” must work together to resolve this). The whole subcontinent, and often Kashmiris themselves, have been trained to think in binaries of India-Pakistan, Hindu-Muslim, Hindi-Urdu.

In school years, while we were fortunate to study English as this gave us a voice and reach beyond the subcontinent, the Kashmiri language (and Dogri in Jammu) was a notable omission. As primary students in Srinagar, we had the “Hindi-Urdu” lecture instead – Hindu (and most Sikh) students would opt to study Hindi, whereas Muslim students would join the Urdu class. There was no formal education in the Kashmiri language. This is the language that bound generations of Hindus and Muslims of the valley (whereas most Sikhs spoke variants of Punjabi or Pahari as their first language, they do know Kashmiri as the native lingua franca of the region). Focus on local language and culture could have united all groups on local issues and interests.

Although initially well represented in the state constituent assembly, early governments, and government services, overall perception towards the later decades was that Sikhs faced a ‘ceiling’ on how far they could rise in government professions. In the Kashmir province at least, there was a perceived bias in favour of Muslims. We have to weigh in the fact that overall state administration seemed to function more by ‘machinations’ as opposed to representative democracy, and we cannot disregard the fact that the violent conflict basically impacted everyone’s prospects adversely regardless of religious affiliation.

Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness… with honour

These are inalienable rights of every human being, but it is also the inalienable rights of every other human being. No belief system, whether religious or political, can treat another person as second class or subject to dictates that lead to denial of these rights. This is not a utopian ideal but something that mature and peaceful societies practice today.

The title is borrowed, but the aspiration dwells in every heart. What do we the people of Jammu and Kashmir want? What do human beings want anywhere in the world? Life, security, prosperity, liberty, clean air, and finally, reliable, accountable, and trustworthy institutions are goals that ALL human beings would seek as individuals and as collective groups. Many regions of the world have achieved these goals to varying degrees, so the world has examples to emulate.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir have diverse cultures, histories, languages, and concerns that are local and unique. But for various reasons, either historic or current, there has been a perceptible lack of a unified voice – not for the outer world, but for dialogue amongst themselves first. This has been surprisingly lacking even in the province of Kashmir, which is perceived to be a lot more homogenous. This perception itself is troubling – because though Kashmiri language, culture, and ethnicity is an important part of Kashmir, so are its minority populations – the Pahari, Punjabi, and Shina language speakers, the people across the LOC who aren’t Kashmiri speaking but speak various Pahari or Punjabi dialects. And now we come to religion – it is undeniable that religion is the primary marker of identity for Kashmiris and many South Asians. Kashmir has, therefore, come to be seen as a ‘Muslim’ province and ‘Jammu and Kashmir’ as a ‘Muslim’ state. Yes, it is a Muslim majority, but this focus on one particular religious group created situations where the state’s many minority voices simply get side-lined and creates situations which an openly Hindu-nationalist Indian regime can exploit. To start with, the state never got to exercise meaningful democracy. Because of the subcontinent’s trauma with Punjab’s partition on Hindu-Muslim lines, this has been the only criteria for any engagement whatsoever.

Chittisinghpora massacre: The site of killings near the gurudwara, preserved by the villagers by marking the bullet holes on the wall.

Introspection

Outside powers with an eye on Kashmir are able to exploit internal differences when our internal discourse isn’t straight. Internally, within the state, our democracy should have ensured that all regions and all sections of society were adequately represented. Whereas interference starting from 1953 had an undeniable adverse impact, there were clearly shortcomings in the state’s policies – there was a paranoia around ‘demographic change’ that meant the state failed to redress the situation of Sikh and Hindu refugees from the other side of LOC (even referring to them as ‘west Pakistan’ refugees is an active denial of the fact that areas of Poonch, Mirpur, Muzaffarabad faced a complete annihilation of their non-Muslim populations). These people were state subjects and yet lived like refugees for three generations. The situation with the Valmiki community who had served the state for decades was similar, they did not have full rights as permanent residents. As a diaspora Kashmiri, I wouldn’t expect to be treated second class (or would avoid living in a place where I might be), and yet, in our home, we failed on these fronts.

It is one thing to protest artificially engineered demographic aggression, and quite another to treat people with fairness, who by every standard have earned rights by virtue of their residence and contribution. If anything, the plight of Valmikis and others was exploited to justify the sinister settler-colonial project, against which, all peoples of Jammu and Kashmir should have had common cause.

We cannot control or change the past, but how we present our narrative today is in our control. Of foremost importance is intellectual honesty. Kashmiri intellectuals need to understand that the terrible events surrounding the Jammu massacre of a sizeable number of Muslims (reported November 1947) had equally terrible parallels with the complete annihilation of non-Muslim populations from across the LOC – And in turn, there were abhorrent events in neighbouring Punjab where both sides eliminated and expelled ‘the other’– we must guard against the tendency to present one event as a consequence of another.

Finally, all our communities need to hear each other out – whatever our ideologies or political views. When people with even the most extreme views are given an opportunity to present and justify them to an audience, they can get discredited fast (whereas it is easy to see how even legitimate political views are maliciously labelled as ‘extremist’).

We need to understand and respect the regional cultures and sensibilities of the state. No side can change the past and events of 1947 were not in control of anyone living today. The least we can do is acknowledge that wrongs were committed, the circumstances under which they were committed, and most importantly, why we must never allow a repeat. The focus here is on we – people of the state of Jammu and Kashmir who have all the capability (and right) to come together to define our future.

When I heard the news the early morning of the 5th of August, my first instinct was to download the state constitution and assembly debates. As an IT professional, I took hash measurements of the files and shared them with friends. I expected such documents to either disappear or be tampered with, but these measurements could be used to verify the integrity of all copies. In those documents, are some of the first examples of how people of the state first elected their representatives to speak for them – to speak with each other, there were representatives elected from all communities including many Sikhs, all working together, to create a better future.

References

- Friedman, T (2005). The World is Flat, A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux : New York.

- Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J. (2012). Why Nations Fail; The Origins Of Power, Prosperity, And Poverty. Crown Publishing Group : New York.

- Aljazeera (5 August 2019). ‘Kashmir special status explained: What are Articles 370 and 35A?.’ Aljazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/08/kashmir-special-status-explained-articles-370-35a-190805054643431.html

- Iqbal, N (21 June 2019). ‘Amarnath Yatra: Secure highway links, says CRPF.’ Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/amarnath-yatra-secure-highway-links-says-crpf-5791592/

- Bhat, A (21 March 2019). ‘Names of killers still reverberate in my ears’: 19 years after Chittisinghpora massacre, lone survivor recounts night that killed 35 Sikhs.’ Firstpost. Retrieved from https://www.firstpost.com/india/names-of-killers-still-reverberate-in-my-ears-19-years-after-chittisinghpora-massacre-lone-survivor-recounts-night-that-killed-35-sikhs-6299441.html

- (30 May 2020). ‘Burglars loot cash from gurudwara in Srinagar’. KashmirLife. Retrieved from https://kashmirlife.net/burglars-loot-cash-from-gurdwara-in-srinagar-234872/

- (25 May 2020). ‘Pak man held for vandalising UK Gurudwara, leaves note on Kashmir.’ the quint. Retrieved from https://www.thequint.com/news/india/pakistani-man-arrested-for-vandalising-gurudwara-in-england

- Singh, A.(12 January 2019) Kashmir: Sikh Panchayat Leaders in Pulwama Resign After Militants’ Threats. The Wire. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/rights/kashmir-sikh-panchayat-leaders-in-pulwama-resign-after-militants-threats

- Bhat, S. (10 June 2020) ‘Panic among panchayat leaders after murder of sarpanch in Kashmir Valley’. IndiaToday. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/panic-among-panchayat-leaders-after-murder-of-sarpanch-in-kashmir-valley-1687586-2020-06-10

- (13 June, 2019). ‘The Supreme Sikh body urges solidarity with Kashmiris following revocation of special status.’ SIKHPA. Retrieved from https://www.sikhpa.com/supreme-sikh-body-urges-solidarity-with-kashmiris-following-revocation-of-special-status/

- ‘Massacre at Baramulla’ in Tony Grant (ed), More from Our Own Correspondent, London: Profile, 2008, pp.294-7

- ‘Mission in Kashmir’ by Andrew Whitehead pp102: “23 October: ……Jammu had been beset by an armed rebellion against the maharaja, and by intense anti-Muslim violence in which the maharaja’s forces were reported to be complicit. On landing in Srinagar, they were told about the scale of the tribal raid launched very early the previous day. They initially appear to have believed that the state forces would be sufficient to repulse the invaders, perhaps unaware that a considerable number of the maharaja’s Muslim troops had either mutinied or deserted. As soon as the seriousness of the tribal invasion became apparent, there was frenzied diplomatic activity

- Christopher Snedden ‘Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris’ (pp167) “…while the violence against muslims in Eastern Jammu province was alarming, Muslims in western part of the province concurrently engaged in similar diabolical acts….”

- Andrew Whitehead 2013 ‘The Kashmir Conflict of 1947: Testimonies of a Contested History’: “…Much of the earlier writing about Kashmir, including well researched accounts of its history, has been tarnished by partisan comment…”

- Christopher Snedden, ‘Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris’. p167: “…Many Hindus from Mirpur and Muzaffarabad not killed became internally displaced people within J&K, although, to their chagrin, the J&K government never formally granted them this status” [Also concurs with personal testimonies of the affected families]

- The bulk of “Jammu Massacre” of Muslims in which section of state troops are said to have been complicit and reportedly aided by combatants from Patiala seems to have taken place in November of 1947 – this is as per newspaper reports from the time that are widely circulated. (but as noted by Christopher Snedden, violence and counter-violence against different groups was concurrent on both sides of the province of Jammu, whereas it had been happening since summer in neighbouring Punjab). Sadly, while our aim ought to have been to understand and prevent communal violence in general, partisan groups often engage in establishing who did what first – I doubt it is possible or even useful to establish what triggered violence and counter-violence.

- Christopher Snedden ‘Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris’ (pp167) “…while the violence against Muslims in Eastern Jammu province was alarming, Muslims in western part of the province concurrently engaged in similar diabolical acts….”

About the Author: Jang-Vijay Singh is a Baramulla born IT professional based in London with strong ties of family and ancestry to Kashmir. He has an MSc in Software Engineering from the University of Oxford.

All our work is available free of charge, if you wish to support our work by making a donation, so that we can continue to provide this vital service, please do so here.

This opinion article forms part of Kashmir Reading Room’s Yearly Report Aug 2019-Aug 2020. You can view the full report by clicking on the button below.

Disclaimer

The author(s) of every article and piece of content appearing within this website is/are solely responsible for the content thereof; all views, thoughts and opinions expressed in all content published on this site belong solely to the author of the article and shall not constitute or be deemed to constitute any representation by JKLPP, Kashmir Reading Room, the author’s employer, organisation, committee or other group or individual, in that the text and information presented therein are correct or sufficient to support the conclusions reached.